You are here

Role of strategic surprises in 1098 Battle of Antioch

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Oct 12,2024 - Last updated at Oct 12,2024

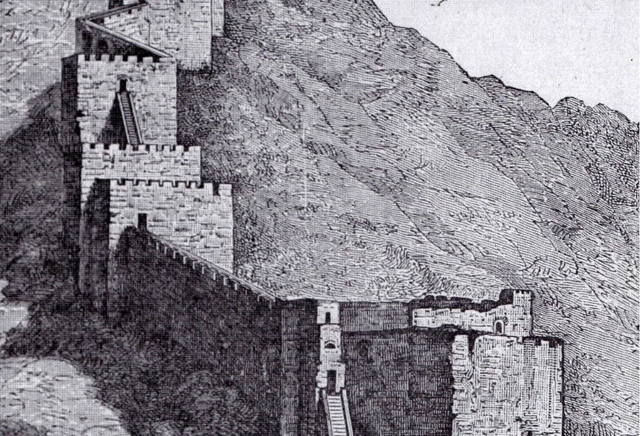

Byzantine walls of Antioch, 19th century engraving by R.Turner (Photo of Carmichael Digital Projects)

AMMAN — After diplomatic efforts were exhausted, the final confrontation between Crusaders and Kerbogha coalition took place at Antioch in 1098. The Muslim coalition was reduced in number due to desertion of Turkmen troops who were dissatisfied with the course of the campaign. As Kerbogha sought a battle, he had to obtain intelligence on the Crusaders and he did not have accurate knowledge about the size and capabilities of his enemies.

"In addition to the poor knowledge of the exact state of the crusaders’ army, it appears that their sally took Kerbogha by surprise; narratives inform us that the Muslims were preparing their meal when they learned about the sally as the crusaders found cooked meat in the Muslim camp after the battle," said French historian Thomas Brossett, adding that this surprise was due to the successful misinformation game played by the Crusaders.

“It must therefore be noted that, while the surprise was a factor, the deployment of the Crusaders through a single narrow gate took time. This gave the Muslim besiegers time to react and deploy before being attacked by the Crusaders,” Brossett continued.

However, the surprise allowed the crusaders to deploy in the face of a smaller force than the entire coalition and limited the risk of being attacked during the deployment.

"Previous studies have claimed that Kerbogha’s failure to attack the crusaders while they were deploying led to the Muslims’ defeat. France specifies that it was the dispersal of Muslim troops around the city of Antioch that made it impossible for them to attack the crusaders in time, arguing that this was a decisive mistake," Brossett underlined, adding that it was not a mistake, however, as, in order to efficiently besiege Antioch, the coalition had to be split into multiple contingents blockading the city’s gates.

Furthermore the 2,000 men of the coalition guarding Bridge Gate were the only forces available, and were shown unable to oppose the 20,000 – 30,000 sallying Crusaders.

The surprise of the sally and the dispersal of the coalition were decisive in the crusaders’ success, but not Kerbogha’s mistake. By that point, the surprise of the sally denied Kerbogha the possibility to attack the crusaders during their deployment, adding to the uncertainty that troops would commit sufficiently to the battle, and placing Kerbogha in an uncomfortable position.

The crusaders succeeded in deploying their army before the Muslims could attack them, so Kerbogha decided to adopt a risky but necessary battle plan to defeat the fully deployed crusading army, the historian from The University of Lancaster, noting that Kerbogha wanted to encircle the Crusaders and cut off their potential retreat.

"He would command a main corps, while a likely smaller second corps would attack the rear of the Crusading army. The battle can be divided into three phases: the attack on the crusaders’ rear by the second corps, the first shock encounter between the two forces leading to the flight of the remaining Turkmen, and, finally, the defeat of the last standing emirs," Brossett said.

First, the second corps was sent against the rear of the crusaders, but the former rapidly broke and fled showing the troops’ lack of commitment to the battle. This lack of commitment is especially well described by Ibn Athir who wrote that “The Franks […] thought that it was a trick, since there had been no battle such as to cause a flight.”

Second, the main corps engaged with the crusaders, but Turkmen fled, arguably disorganising other lines behind them. This was the evidence of the overall lack of motivation by the Karabogha's troops and third, the Crusaders charged the remaining coalition forces and defeated them.

Most Muslim cavalry units managed to flee the battlefield while infantry was not lucky enough to avoid being massacred.

“However, the battle plan was wise, and there was no alternative plan capable of achieving the complete destruction of the crusading army,” Brossett argued, but the tactics was not supported by the commitment of the troops on the ground.

It was previously thought that the Muslim coalition had the numerical advantage but after the months of campaigning their size was significantly reduced to 6,000 to 8,000 cavalrymen and 10,000 to 15, 000 infantrymen. They were facing 20,000 to 30,000 well equipped Crusaders

"In addition to their advantages in both numbers and quality, the crusaders’ morale was increased by having routed major portions of the coalition’s forces and the coalition had suffered a major blow to morale. By the beginning of the third phase, the coalition was already lost," Brossett highlighted.

The failure of the 1098 campaign is, in fact, part of a larger phenomenon as successive Muslim coalitions similarly failed, such as those of Sharaf Dawla Mawdud (ruled between 1109–1113) in 1110, 1111 and 1113.

Another defeated coalition – led by Bursuq Ibn Bursuq – was defeated at Tell Danith in 1115, Brossett continued, adding that the constant failure of the Muslim coalesced forces in the early decades of the Frankish presence in the Levant suggests another reading than the repeated individual incompetence of their commanders.

"Muslim combined forces suffered from both a structural failure of their military organisation, arising from overreliance on Turkmen auxiliaries, and unbridgeable rivalries between the commanders of their regular forces," Brossett concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Kerbogha mobilised a coalition of heterogenous Muslim emirs from Jazira in order to meet crusaders at Antioch.

AMMAN — One of the first major campaigns of the First Crusade was the siege of Antioch in spring of 1098.

AMMAN — Historians often underestimate the duration of the Kerbogha campaign against Crusaders, most historians based the start of the campa