You are here

Kerbogha’s coalition: Antioch’s siege during Crusades

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Sep 17,2024 - Last updated at Sep 17,2024

Peter the Hermit, leading People's Crusade (Photo of miniature from Egerton Manuscript 1500)

AMMAN — Kerbogha mobilised a coalition of heterogenous Muslim emirs from Jazira in order to meet crusaders at Antioch. They were later joined by other Syrian contingents and a large Arab force led by Wathab Ibn Maḥmud.

However, Muslim leaders had opposing political agendas, and it directly harmed the campaign at Antioch. According to Kohler, emirs realised that the greater threat to their independence lay with Kerbogha rather than with the crusaders and that they had little interest in seeing the campaign accomplish its goals. Therefore, they undermined the efforts of Kerbogha as much as they could.

Volunteers also joined the main army motivated by a call for jihad and they were not professional soldiers and their value in the battlefield was rather poor.

More importantly, large numbers of Turkmen completed the coalition, likely comprising most of the army and they were freemen cavalry units.

"They were competent nomadic horse archers but lacked discipline, making it difficult to command them as a homogenous force and to control their hostile behaviour towards local inhabitants, even in allied lands," said French historian Thomas Brossett, adding that their Islamisation was certainly incomplete by the late 11th century, which means their primary motive was to enrich themselves, not religious devotion.

“Maintaining Turkmen for more than a few weeks was nearly impossible if booty was lacking since they would become reluctant to fight or would disburse”, Brossett explained, noting that the various forces composing the Muslim coalition had never fought together and it was uncertain whether they would be able to fight uniformly together in battle.

"In contrast, the crusaders’ army was composed of battle-hardened troops that developed a high level of battle cohesion throughout the entire campaign. Consequently, the coalition had structural flaws that were decisive in the coalition’s failure," the scholar underlined.

Despite Mediaeval sources, it is usually difficult for researchers to estimate the size of an army. Ancient scribes and historians tended to overestimate their number.

Estimates of Kerbogha army go from 15000 to 60 000, even 90 000.

"Zouache emphasises that the coalition no longer massively outnumbered the crusaders before the Battle of Bridge Gate, as there had been significant desertions. Therefore, France’s estimate likely corresponds to the coalition at its peak, while other estimates portray the coalition after the massive desertions that happened in front of Antioch. The coalition faced a crusader army of 20,000 – 30,000 men," Brossett highlighted, adding that these numbers need to be taken for what they are – estimates based on especially unreliable data.

While the nature of the narratives does not allow any definitive estimate of army sizes, it is clear that the coalition was of exceptional size. This represented a major challenge for Kerbogha, who had never controlled such a large army in the past.

"Leaders of the First Crusade experienced a similar challenge. However, they had over eight months – from around mid-August 1096 to May 6th 1097 – to get both their logistical and command systems working before reaching Nicaea and facing enemies," Brossett said, adding that they designed successful systems used throughout most of the First Crusade, obtaining resources directly from the region, instead of waiting to be resupplied from distant bases.

With a similar number of men, Kerbogha had to address those challenges in less than a month, which was too short to find a working system. Consequently, the coalition’s “great size was at once its biggest strength and its greatest weakness”, Brossett concluded.

Kerbogha’s had two main objectives-to repel crusaders and to consolidate his power over Syria. This is why he made aiding Antioch conditional on the ceding of the citadel to his trusted man – Aḥmad Ibn Marwān. The same personal ambitions motivated other Jaziran commanders in leading Islamic coalitions in Syria.

However, Islamic coalitions always faced local emirs’ determination to maintain their own independence. That lack of unity was one of the main factors for why these Islamic coalitions failed.

"From Kerbogha’s point of view, besieging Edessa could have been a way to strengthen the unity of the coalition by granting Edessa as an iqta to one of emirs," Brosset underlined, adding that with the benefit of hindsight, historians including Hans Mayer have claimed that laying siege to Edessa “vainly” wasted time that was badly needed to relive Antioch, delaying a confrontation that, if undertaken earlier when the coalition had been at its largest, would have allowed the greatest chance of success

"However, this argument should be discarded – for, if Kerbogha had ignored Edessa and rushed towards Antioch, he would not have been able to merge his forces with those of Syrian emirs, considerably reducing the size of the coalition. This is why Harari claims that besieging Edessa was a way to make time for the Syrian emirs to arrive," the historian underscored.

In addition, the crusaders, despite a months-long siege, had not breached Antioch’s defences, and the inhabitants were not starving. Yaghi Siyan still firmly held Antioch when Kerbogha arrived in the Edessan territory on April 15 1098.

No reasons were pushing Kerbogha to rush towards Antioch. Furthermore, modern historians know that Kerbogha’s objective was to attack the crusaders in front of Antioch, but this is the benefit of hindsight, Brossett said, adding that narratives do not provide evidence that the crusaders at Antioch knew of Kerbogha’s objectives before he left Edessa.

"In fact, the crusaders’ actions at the siege of Antioch hint towards their being unaware of Kerbogha’s march towards Antioch before a messenger sent from Edessa warned them, likely on May 28," Brossett said.

The intensifying of crusaders' activity following the arrival of the messenger to urge the capture of the city certainly suggests the crusaders’ ignorance of Kerbogha’s objective before his departure from Edessa on May 25th 1098.

Antioch was taken by betrayal and the treason was probably masterminded once crusaders learned that the Muslim coalition had left Edessa and was marching towards them.

Related Articles

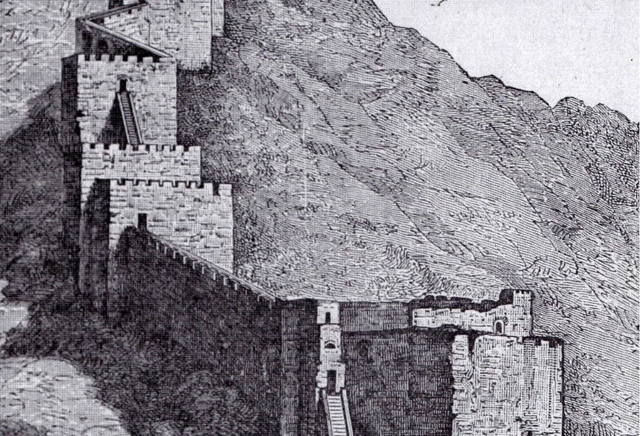

AMMAN — One of the first major campaigns of the First Crusade was the siege of Antioch in spring of 1098.

AMMAN — Historians often underestimate the duration of the Kerbogha campaign against Crusaders, most historians based the start of the campa

AMMAN — After diplomatic efforts were exhausted, the final confrontation between Crusaders and Kerbogha coalition took place at Antioch in 1