You are here

A labour of love spreading peace and harmony

By Ica Wahbeh - Nov 14,2017 - Last updated at Nov 14,2017

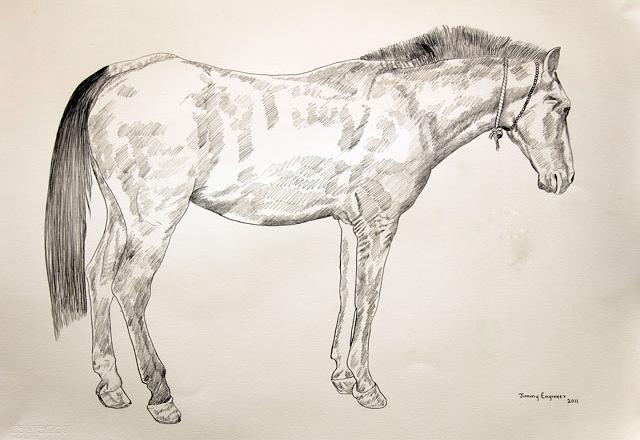

Work by Jimmy Engineer from the ‘Lines That Talk’ exhibition on display at the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts through November 25 (Photo courtesy of the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts)

Nothing in the soft-spoken bearded man clad in salwar kameez gives an inkling that he is famous, but Pakistani artist, social worker, philanthropist and stamp designer Jimmy Engineer is an international artist and a global citizen who loves and cares for fellow human beings, especially the less fortunate.

But, above all, he is a “servant of Pakistan”, a name by which he does not mind going. And a being striving for excellence.

“All my life I wanted to achieve excellence. I wanted to show that Pakistan can be as positive and creative as any other nation. I served for over 40 years my country. In all exhibitions I promoted the positive side of Pakistan.”

And many are the countries and the exhibitions he held in the course of his life as an artist, so far: over 80 exhibitions in both his native country and abroad.

His works are in private collections in 28 countries; the themes are historical, philosophical, land and seascapes, architectural and cultural compositions, both figurative and abstract, calligraphy, portraits and miniatures.

The artist’s name is the result of a Zoroastrian tradition whereby the profession becomes the name. Both his father and grandfather were engineers, a tradition he did not follow, having different inclinations early in life.

“I started drawing and using powder colours when I was 4,” he says giving an overview of his life and work at the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts where he is exhibiting paper prints of his original oils on canvas and original drawings on paper.

His teacher?

“Nature.”

And when you learn from a perfect mentor, “you will always remain a student”, he says with sincere humility.

When he was six, in 1960, doctors gave him three months to live because his kidneys were failing. He defied medicine and nature — subsequent X-ray showed he had “two new kidneys” — in an act he considers a “second chance”. And because he was given this second chance, he believes he has to give back.

He does, generously.

“Nearly all my proceeds go to charities dealing with blind children, orphans, prisoners, widows, homeless and sick people.”

It makes this altruistic artist who lives in a two-room rented house happy to give.

“For me it is important to be a good human being. To serve humanity.”

Which he does through his art.

His charity work, including the many walks for different causes, is all about changing perceptions: of his country, Pakistan, when he exhibited in the US or Europe, of children with special needs when he took them to public spaces — zoos, 5-star hotels, restaurants — of inmates, particularly juvenile, for he believes “nobody is born a criminal. Society makes them what they are”.

His dedication has contributed to the bettering of the lives of hundreds of people, in his home country and elsewhere. But he also wishes to spread the message of peace and raise awareness about problems plaguing people, for which, besides painting, he would walk: for cancer, leprosy, education, law and order.

In one instance, in 1994, he went on an arduous 4,000-km walk on foot, sleeping in villages, “seeing what people need”. In 2001 he walked for peace between India and Pakistan, “daring” to pin the flags of both countries on the long white shirt he walked in — “now in the Peace Museum in Beijing” — an act of courage and peril.

Spreading harmony and peace seems to be his mission in life.

In 2009, after an exhibition in Houston, Texas, the mayor made Engineer an honorary citizen of the city and a goodwill ambassador.

His good deeds are too many to mention. Talking to this unassuming man one would not guess that Mother Theresa knew and embraced him, that personalities far and wide court him, that he received accolades, travelled the world over and received over 70 Shields of Honour from various Pakistani and foreign organisations.

The prolific artist spent three years at the National College of Arts. He left without waiting for his degree, a paper validating an obvious talent, and has been living in Karachi ever since.

His works count over 3,000 paintings, more than 1,000 calligraphic works, over 1,500 drawings and 700,000 prints in private collections.

He paints in different styles, always claiming to be the disciple of a perfect master, nature, and, as such, having to perpetually learn more.

Seeing his works, it is difficult not to find him modest.

The drawings, original, are mostly magnified details of the bigger paintings. The lines flow easily, masterfully, meeting and separating to form images of tender parent-child love, caring beings helping or consoling each other, sadness and desolation, or peaceful animals from some bucolic landscape the artist must have seen in his many walks.

The exhibition could not have had a more apt title, “Lines That Talk”, because Engineer’s lines do indeed tell stories of myriad people.

Like in the prints of his oil paintings — which must be a wonder to behold — which tell the story of the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan, with all the accompanying human dispossession, misery and tragedy.

They are also a “tribute to the struggle and sacrifices of the hundreds of thousands of men, women and children who created Pakistan”.

The images show masses in flight from burning villages, caravans, huddled people under a tree, the story of refugees everywhere, maybe more poignant here, where the narrative of dispossessed Palestinians is so familiar.

The colours, earthen with much reddish-maroon tint, are warm, soothing, almost belying the images they create.

Engineer’s architectural compositions are a labour of love. Painstaking details, layered, rich, images reflect Pakistani architecture, but also structures from India, Yemen, China and several other countries.

The compositions are such that “no building is off balance, jumping around”. Dense, yet with each image enjoying primacy, the filigree details of mosques, churches, buildings keep the eye prisoner, hungry for more.

The idea, in the artist’s 58 architectural compositions is that “if architecture [of different countries] can be brought together, people can be brought together”. Not surprising for someone seeking peace, harmony and the wellbeing of fellow human beings.

The “lines” Engineer makes talk are mesmerising. A quick glance would not do. One needs time to take all the details in, and then go over the images again and discover, with surprise, so many overlooked.

The exhibition runs through November 25.

Related Articles

AMMAN — “Being a good human being is more important than being a world-recognised artist,” said Pakistani artist Jimmy Engineer, who devoted

Women — who suffer most in times of conflict — are predominant in Leila Kubba Kawash’s paintings exhibited at Orfali Art Gallery.

DAFEN, China — Painters in a Chinese village once known for churning out replicas of Western masterpieces are now making original art worth