You are here

American scholar explores link between Mamluk coin design, economic challenges

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Feb 01,2022 - Last updated at Feb 01,2022

A dirham minted in Cairo in 1415 (Photo courtesy of Warren Schultz)

AMMAN — Coin design during the Mamluk Sultanate led to economic challenges, noted an American historian.

Many scholars believe that sultans in the 14th and 15th centuries undervalued silver currency and overproduced copper coins, which led to inflation said Professor Warren Schutz from DePaul University in a recent e-mail interview with The Jordan Times.

“One of the major factors was certainly the lingering effects of the Bubonic Plague pandemic of the late 1340s and the recurrent outbreaks that subsequently revisited the Sultanate,” said Schutz, adding that population loses in Transjordan contributed to a fall in agricultural revenue and the decay of irrigation infrastructure—this latter with long term implications.

Schultz said the Mamluk-era historian Al Maqr’zī believed that many economic issues arose from the way sultans issued excess copper coins.

“In two of his shorter treatises he laid much of the blame for contemporary economic hardship at the feet of the Sultan Barq’q, emphasising in particular that the sultan and his officials issued exceedingly large numbers of copper coins called fulūs,” said Schultz.

He noted that this explosion of copper coinage has been interpreted by some modern scholars to have contributed to the disappearance of silver coinage.

From the tumultuous decade of the 1250s when the Mamluks seized power across Egypt and Syria up until 1412, Mamluk silver coins were essentially the same, even though they did not all look the same, Schultz said, adding that there were many design differences such as words inscribed on the coins, the use of a variety of decorative frames around those legends, or the appearance of small ornaments.

Despite these visible differences, he continued, all these dirhams shared two important characteristics which meant that they circulated and were valued in the same way.

“First, the fineness of their silver alloy was consistently at or near two-thirds silver and one-third copper. Secondly, they were minted at irregular weights,” Schultz said.

In this situation, heavier coins would obviously be worth more than lighter coins, he said, adding that thousands of Mamluk dirhams from this time period survive, and their individual weights can vary from less than one gramme to more than seven.

“In other words, they were not minted so that all the coins weighed a specific and exact amount. The repercussion of this is that these coins did not circulate by count but by weight. Thus, in all but the smallest transactions, these coins were not counted out individually as one would do with one-half JD coins today,” Schultz said.

“Ahli Bank Numismatic Museum in Shmeisani is a great resource for scholarly research,” Schultz said.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Islamic monetary history is a largely unexplored field for researchers due to resource constraints and limited source material, acco

AMMAN — The Eastern Mediterranean and the Biladi Sham, also known as the Greater Syria, regions were linked to other regions through trade r

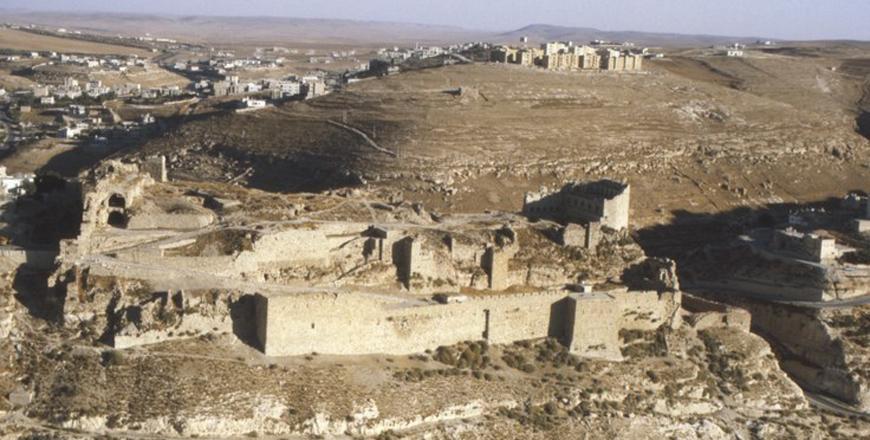

AMMAN — A glass disk fragment found in Shobak poses many questions about the item’s origin and whether it was a part of an “Egyptian merchan