You are here

Racing towards fulfilment

By Sally Bland - May 26,2019 - Last updated at May 26,2019

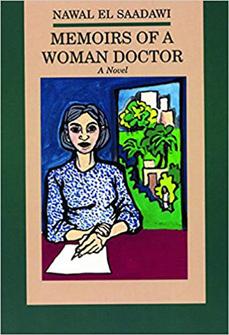

Memoirs of a Woman Doctor

Nawal El Saadawi

Translated by Catherine Cobham

London: Saqi Books, 2019

Pp. 102

Long known for publishing daring, high-quality Arabic literature in English, Saqi Books has initiated a new project this year. It is called Saqi Bookshelf and will include new editions of modern classics as well as other original fiction from the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. The first titles in this series are the renowned Egyptian feminist Nawal El Saadawi’s “Memoirs of a Woman Doctor”, “Love in the Kingdom of Oil” and “Zeina”. In July, Saqi will publish “The Quarter”, a collection of recently discovered writings by Naguib Mahfouz.

First published in Arabic (Cairo, 1958), “Memoirs of a Woman Doctor” has retained all its original energy and relevance. Although in the interim, women have fought for and won many new rights, most of the issues highlighted by Saadawi are still contested today. The book reveals her naturally acquired feminism, having been written when she was in her twenties and had not read any feminist literature. Rather, as she states in the Author’s Note of the original English edition of 1988, while not autobiographical as the title implies, it “expressed my feelings and experiences as a woman who was a doctor at work, but still performed the roles of a wife and a mother at home”. (p. 7)

How many women still feel the frustrations involved in trying to juggle these demanding roles?

A pent-up, almost frantic urgency runs through the first half of the story as the protagonist chronicles what she calls “the conflict between me and my femininity”. She experiences this conflict most tangibly in reaction to the privileges enjoyed by her brother and denied to her — his getting a bigger piece of meat, being exempted from household chores, and perhaps most irking, being allowed to run free outside. Running, jumping and aspiring to fly are her greatest desires, but she is often curtailed. “Shameful! Everything in me was shameful and I was a child of just nine years old… I wept over my femininity even before I knew what it was.” (p. 10)

Her only consolation was that her brother couldn’t fly either. “I began to search constantly for weak spots in males to console me for the powerlessness imposed on me by the fact of being female.” (p. 11)

This rebellion against not being able to live life to the fullest continues and intensifies during puberty, punctuated by small instances of sexual harassment and the appearance in her home of the first suitor. It builds up to her leaving the house without permission and having her long hair cropped short, an act to which her mother reacts violently.

Graduating from secondary school at the top of her class, she chooses to study medicine for the respect that it engenders and enters the world of science which gives her new evidence that the restrictions imposed on women have no basis in material reality. But she is also terrified by the prospects of having bound her life to sickness, pain and death. Realising that humans are separated from extinction by only a hair’s breadth, “Science toppled from its throne and fell at my feet naked and powerless, just as man had done before.” (p. 40)

Having until then been racing towards fulfilment, the protagonist is plunged into a crisis by her realisation of the limits of science, leading her to withdraw to a remote village. But this retreat also engenders the solution. Here, for the first time, she sees a patient “as a whole person, not a loose assemblage of discrete parts” (p. 46).

She begins to develop her emotional side, discovering compassion and her own humanity, returning to the city, reconnecting with her family and eventually seeking male companionship on an equal basis. She attains an inner calm, realising that it is her will which guides her behaviour, and embarks on her work as a doctor with new determination to protect young girls in particular who are threatened by their families and/or unjust traditional practices. “Since childhood I’d been immersed in a series of endless battles and here I was up against a new one with society at large.” (p. 80)

But by now she is up to the challenge.

Though not a memoir, this novel certainly has an autobiographical aspect, as it traces the early evolution of Nawal Saadawi’s thinking, especially the sharpening of her critical powers, as well as her drive to act upon her principles, which placed her in the vanguard of the modern Arab women’s movement. The swift interplay between the protagonist’s emotions and her sense of justice are compelling, and the rich sensory detail and impulsive way in which she tells her story makes it all the more genuine, and at least as effective as theoretical feminist writing.

Related Articles

LONDON — "When I was in jail, the jailer said, 'If I find paper and pen in your cell, it's more dangerous than if I find a gun,'" Egyptian f

The Bride of AmmanFadi ZaghmoutTranslated by Ruth Ahmedzai KempHong Kong: Signal 8 Press, 2015Pp.

Bad Girls of the Arab WorldEdited by Nadia Yaqub and Rula QuawasAustin: University of Texas Press, 2017Pp.