You are here

‘Ancient Levant practice of modifying skulls increased with rise in temperatures’

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Mar 23,2019 - Last updated at Mar 23,2019

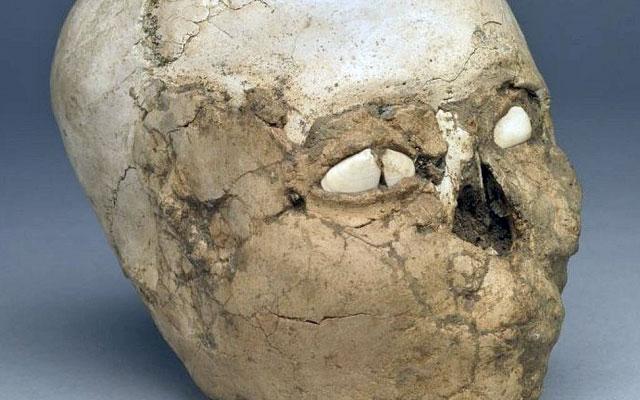

In this undated photo, a 9,500-year-old Neolithic plastered skull from the British Museum's collection can be seen (Photo courtesy of the British Museum)

AMMAN — The removal and modification of skulls in the Levant was documented for the first time during the Natufian period around 11,000 years ago, and it continued for another 500-3,000 years into the end of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) period, a Jordanian scholar recently told The Jordan Times.

“Crania plastering was common in the PPNB period in the 3rd millennium BC; the first plastered skull was discovered in Jericho in 1953 by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon,” said Aven Qatameen, who received her Master’s degree in archaeology at The University of Jordan.

Moreover, the practice was later revealed at additional sites dating back to the PPNB in the Levant at Jericho, Tell Ramad, Tell Aswad, Beisamoun, Nahal Hemer, Ain Ghazal and Kefar Hahoresh, she said, adding that during the PPNB (7,000-8,800 BC), the treatment of human skulls took a more varied approach.

According to Qatameen, “The number of treated skulls increased within the region and were found within agricultural villages of all sizes, as in Ain Ghazal.”

In order to create realistic features of deceased people, several treatments and modifications were applied to the removed skulls and this was accomplished by plastering or painting the skulls, and by using clay, gypsum, bitumen or lime on the crania or face of the skulls — mainly after the decomposition of the tissues or after the drying of the skull, the researcher emphasised.

There are theories about why ancient people removed skulls from the deceased’s bodies, the concept of “skull worship” was “first debated by Kenyon after she discovered them in Jericho, Qatameen noted.

“Since then, additional burials have been discovered with different stylistic approaches and Kenyon’s interpretations were widely accepted by other researchers,” Qatameen said, adding that the practice of skull removal could have been a cult ritual associated with leaders of a group or clan within residential settlements, likely related to ancestral worship.

“Kenyon also believed that skulls belonged to enemies who had kept them in memory of their defeated,” she noted.

The Jordanian scholar maintained that new theories on why these skulls were removed include reasons related to the crafting of a social memory through images, an assertion of individual and group identities in past and present communities, an enhancement of communal identity and reaffirmation of belief systems, the creation of private property and for marking land and territories.

“The PPNB corresponds with climate amelioration, which influenced the culture by the environmental change of the ancient Middle East climate,” Qatameen noted, adding that the climate became warmer in the Holocene era, and the Neolithic period is considered to have ushered in the Agricultural Revolution.

“This led to socio-demographic changes, size and distribution of the settlements’ populations, architectural development and the emergence of mega-sites... This period required a lot of work, assistance and cooperation,” she stressed.

Qatameen said that it is also important to assess why many sites were abandoned during the Late PPNB period in the south and central Levant. She added that there may have been a gap in or problem with the indigenous population.

“Fluctuations in population size that occurred during the PPNB and population dispersion attributed to overexploitation could have also been due to the environment or to the influence of previous generations... This may have provided the impetus for population movement to the steppes,” Qatameen concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The transition in burial practice and rites during different phases of the Bronze Age intrigued researchers studying the ancient sit

AMMAN — The area surrounding Lake Tiberias, the Jordan River and the Dead Sea hold a special place in history, as they witnessed many import

AMMAN — The Neolithic in the Levant was characterised by the first sedentary farming communities in the world and the transition from huntin