You are here

Neolithic period in Levant witnessed ‘fundamental transformation’ of humanity — scholar

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Oct 09,2022 - Last updated at Oct 10,2022

The upper layer of the cache of plastered human statues and busts at Ain Ghazal (Photo courtesy of ACOR/Rami Khouri Collection)

AMMAN — The area surrounding Lake Tiberias, the Jordan River and the Dead Sea hold a special place in history, as they witnessed many important human milestones, noted Professor Edward Banning from the University of Toronto.

“These include the settlements and substantial architecture and first agricultural communities, the earliest pastoral nomadism, some of the earliest portrait statuary and some of the earliest steps towards economic inequality and political complexity,” Banning noted.

He added that all of these developments took place at least partially during the Neolithic period, which began over 10,000 years ago and continued through 4,500 BC.

The Neolithic in the southern Levant constitutes one of the most compelling objects of archaeological inquiry, the scholar said, adding that the Neolithic period constituted a “revolution” in human economy.

“After more than a million years of living as hunters and gatherers, the inhabitants of this tiny region set in motion a fundamental transformation of our species’ adaptation, with transformations of similar magnitude in settlement patterns and social relations,” Banning stressed.

Neolithic sites also contain multiple types of data about the belief systems of their inhabitants. The first forms of the religions and cultic practices have been documented there, according to the scholar.

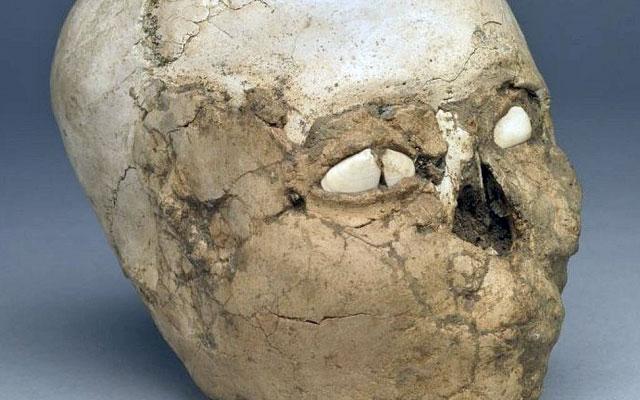

“Burial practices were diverse and show substantial variation over time and various authors claim some buildings may have been shrines, and archaeologists have unearthed a wealth of sculpture, plastered skulls, and clay tokens that gives us glimpses into Neolithic symbolic systems,” Banning said, adding that the variation suggests ascribed social statuses and complex theories about the afterlife.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) burial practices also presaged Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) burials with the practice of skull caching, the scholar said.

“During PPNB, the modal burial type in Ain Ghazal [on the northeastern outskirts of Amman], Jericho, and most other sites is incredibly consistent. The remains of decapitated individuals in single interments beneath the plastered floors of houses occur repeatedly,” Banning underlined.

The fact that burials beneath plastered floors rarely contain intact skulls suggests either that these individuals were decapitated shortly after death, or that survivors were diligent in retrieving skulls after a period of decay, he noted, adding that the latter scenario could imply something akin to festival for the dead.

“The individuality of surviving plastered skulls suggests that they are portraits, and implies that any such festival would have occurred within a few years, if not months, of an individual’s death,” Banning said.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The removal and modification of skulls in the Levant was documented for the first time during the Natufian period around 11,000 year

AMMAN — Human burials throughout Jordan, Palestine, Syria and Lebanon present a pattern that is “bizarre” compared to modern practices, acco

AMMAN — The Neolithic in the Levant was characterised by the first sedentary farming communities in the world and the transition from huntin