You are here

Modern, but not imported

By Sally Bland - Apr 03,2016 - Last updated at Apr 03,2016

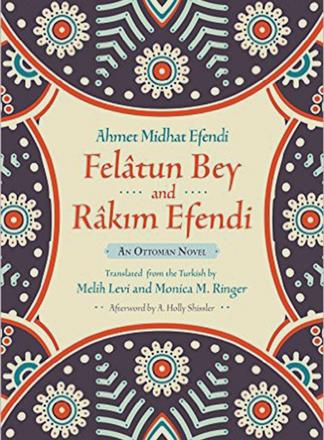

Felatun Bey and Rakim Efendi

Ahmet Midhat Efendi

Translated by Melih Levi and Monica M. Ringer

New York: Syracuse University Press, 2016

Pp. 167

Almost a century and a half after its publication in Ottoman Turkish, Ahmet Midhat Efendi’s short novel, “Felatun Bey and Rakim Efendi”, is still an enchanting read. While rather simplistic in plot and character development, it more than compensates by the nuanced insight it gives into changing times and attitudes in late-Ottoman Istanbul.

Some consider Ahmet Midhat to be the father of the Turkish novel. Like many educated Ottoman subjects of his time, he was preoccupied with his society’s relationship to modernity and Europe, and made it a main theme of this story, causing Orhan Pamuk to credit him with inventing the East-West novel.

The plot builds on the contrast between the two characters named in the title. Felatun Bey is born into riches but squanders his sizeable fortune on a French mistress and gambling, pursuing what he considers to be an alafranga (foreign) life style. Ironically, his name means Plato in Turkish, but his intellectual side is mainly pretention, while his demeanour is often abrasive, and he shows up at his clerical job only three hours a week.

Rakim Efendi is quite the opposite. Born into a family of modest means, he loses his father early and leaves school at 16 to work at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. On his own volition, he becomes proficient in French and a range of subjects, enabling him to earn a comfortable living by tutoring, translation and petition-writing for foreign residents. He gets along easily with Europeans and adapts to their ways when in their company, but his home life is decidedly alaturka.

Obviously, the author is making a moral point about the benefits of hard work and education, but he delivers it in such a humorous way that one doesn’t feel he is lecturing. He satirises Felatun Bey’s show-off version of being alafranga in a teasing way akin to a comedy of manners, replete with a few minor scandals. More crucial for Midhat’s reformist agenda is his use of Rakim Efendi’s character to dissect what it means to be modern, a concept that is not synonymous with foreignness.

Rakim is sensitive, considerate, rational and charming. Ottoman-style, he has an Arab servant and buys a Circassian slave, but their mutual relations are not entirely traditional. Slave proves to be a malleable status as Rakim feels that he has bought Janan’s freedom, and provides her with French and piano lessons, as well as an elegant wardrobe and jewellery. While friends of all types urge him to take her as a mistress, he insists he loves her like a sister. How their relationship will evolve adds a bit of mystery and tension to the story, and makes parts of it serve as a treatise on love and its different varieties, suggesting the idea of companionable rather than arranged marriages.

Midhat is on record as opposing slavery, and the novel was written at a time when the slave trade was being gradually phased out in the Ottoman Empire, yet the author takes the opportunity to show that Ottoman slavery was kinder than its American version.

Midhat’s style is fast-paced and often playful, combining straight narration with lively but subtle dialogue, and frequent author interventions related in a confidential tone as if sharing some well-intentioned gossip, or justifying how the characters are treated. Midhat seems to enjoy drawing comparisons between the alafranga and alaturka life styles wherein the latter are usually shown to be superior, at least for Turks, but without a trace of chauvinism. That’s just how it is, he seems to say.

A. Holly Shissler’s afterword, which contains a fascinating biographical sketch of the author, explains that this was Midhat’s way of critiquing the notion prevalent during the Tanzimat reform era that the Ottoman state and society could be saved by “uncritical and indeed superficial adoption of European modes of life.” (p. 150)

To remind the reader that this novel was written in Ottoman Turkish with Arabic letters, several illustrations of the original text are included, which also show French words printed in Latin letters. Translation of the book was quite a project, as explained in the translators’ note. Special efforts were needed to capture Midhat’s experimental style which “moved rapidly between Ottoman conventions and newer forms of language, syntax, and narration influenced by contemporary French and British novels”. (p. xiii)

The result is a unique, entertaining and enlightening book.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Columbia Global Centres on Tuesday hosted author Isabella Hammad for a book reading and discussion of her debut novel “The Parisian”

HASANKEYF, Turkey — Turkish authorities on Monday conducted a hugely sensitive operation to move a centuries-old bath house weighing 1,600 t