You are here

Ancient strategic landscapes: Insights on Shobak Crusaders Castle

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jul 13,2024 - Last updated at Jul 13,2024

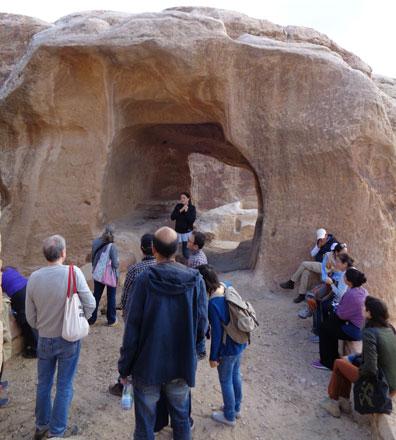

Shobak Castle and its surroundings (Photo courtesy of ACOR)

AMMAN — Shobak Castle, originally built in 1115 by King Baldwin I, was a significant Crusader stronghold strategically positioned to control the King’s Highway and the Petra region. Alongside the fortifications of Habis and Wuayra in Petra and Karak Castle to the north, it played a crucial role in the area’s defence. Known as Montreal Castle to the Crusaders, its importance continued through the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods due to its strategic location on the Hajj Road.

The Italian archaeological mission studied Shobak in 2002 and 2003, concluding that Shobak, Habis, and Wuayra were built on the remains of older Roman/Byzantine fortifications that were part of the “Limes Arabicus”.

The presence of a ruined fort is mentioned in early Islamic written sources, which might explain the short time it took to construct the castle.

“These fortified sites have been interpreted in connection with the imperial route system, but their supposed significance varies according to different models of military site interpretation proposed by various scholars,” noted Giacomo Ponticelli from the University of Florence.

The present study proposes a series of GIS analyses based on visibility factors to test the validity of a military interpretation of the Shobak fort and its relationship with potentially associated sites, such as possible fortifications and watchtowers, Ponticelli continued.

This study particularly aims to assess the possibility that during the Byzantine period, a system of mutual communication or signaling between major sites could have been advantageous, and to test the existence of an indirect connection between Shobak and the major fort of Da’janiya.

“The Da’janiya castellum is located at the easternmost edge of arable land before the desert, while below the foothills of the Shobak fortification, four freshwater springs allowed for the cultivation of trees and crops in the wadis that connect the area with Faynan,” said Ponticelli.

He added that since the presence of a Byzantine fort at Shobak has not been documented in the literature (Macdonald 2015, 89-90), his research aimed to demonstrate that the site could have been part of a territorial control system, possibly coordinated from the fort of Da’janiya, similar to what has been shown for Udruh.

“The sites recorded and dated to the Late Roman and Byzantine periods in the area, associated with both service and defensive functions, should be considered as a cumulative result of surveys conducted around Shobak,” he continued, noting that the same importance was not always attributed to some of the sites discussed here, which may not have shown clear functional features but are still significant.

In the 1930s, American archaeologist Nelson Glueck explored the Shobak area in an attempt to find biblical sites of Edom.

“Research on the Edomite settlement in the highland plateau was conducted in the 1980s by Hart, who also focused on later periods,” said Ponticelli.

The Byzantine fort of Shobak was situated on top of a conical flinty limestone hill, surrounded by four freshwater springs on the northern and southern sides: Ain Mgames, Ain Raghaya, Ain Unsuir and Ain Asi.

Scholarly works published in the past 20 years have reinterpreted Shobak, emphasising the earlier fortifications that were part of the Limes Arabicus.

Related Articles

AMMAN — A group of 10 foreign archaeologists recently concluded a tour of little-known Crusader-era sites in Jordan to learn more about the

AMMAN — With the aim of identifying the urban setting outside the Shobak Castle and its rural resources between 12th and 16th centuries, an

Amman — Karak Castle is the most famous Crusader-Islamic military site in Jordan and appears today as a perfect summary of Crusaders’, Ayyub