It is long past the time that the Western powers and their allies should have reviewed their policy on Syria and decided to come to terms with the Assad regime.

Last week, Bashar Assad won a new seven-year term when more than 88 per cent of those participating in the country’s first multi-candidate presidential poll voted for him.

While the government puts participation at 73.4 per cent, sceptical observers estimate that the majority cast ballots. This means he will not step down as demanded by opponents.

This week, he announced amnesties for army deserters, foreign fighters and kidnappers, and freed several hundred political prisoners. His army is advancing on most fronts while insurgents have been in retreat.

Meanwhile, fundamentalist insurgents of the Islamic Front are battling more radical fundamentalists belonging to Al Qaeda renegade, the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

To Baghdad’s shame and chagrin, ISIL has just taken control of provincial government headquarters in Iraq’s second city, Mosul, and claims to exercise authority over the Nineveh province.

This is a far more dramatic and dangerous development than the ISIL seizing Raqqa, the sole Syrian provincial capital in insurgent hands.

Raqqa is an ISIL asset but does not compare with strategic Mosul, an oil industry city.

Former UN-Arab League envoy Lakhdar Brahimi, whose efforts to mediate a settlement failed, has warned that without successful negotiations, Syria could not only infect its neighbours with extremism, but also be overtaken by warlordism, becoming a new Somalia in the heart of an increasingly unstable region.

Iraq is already on the route to such a destination due to ISIL inroads in Nineveh, as well as the rising against the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad by majority-Sunni Anbar, Iraq’s largest province.

In most of urban Syria, life goes on in spite of the thump of artillery shells striking targets and the whine and crash of mortars.

I visited Damascus and Homs twice in the past six weeks. In both places the battlefronts shift marginally, but the government is gradually reasserting its rule.

On the way to Homs on April 13, we drove along the highway northeast of the capital. The route is bracketed by the outlying towns of Barzeh, on the left, and Harasta, on the right, where insurgents had interdicted traffic.

Once in Homs, however, we could not enter the Old City where some 900 insurgents remained waiting for a truce to be negotiated by faction leaders and Syria’s Reconciliation Minister Ali Haidar.

On June 4, the Barzeh-Harasta route was too dangerous due to snipers in Harasta, and we took the lorry road along the base of the Qalamoun Mountains, where strategic towns and villages had cleared of insurgents over the past two months.

Once in Homs, we were able to walk round the Old City, from which the evacuation of the fighters took place on May 7. We visited key sites and spoke freely to people who either never left or returned, either to stay or to assess the damage to their property.

Homs, Syria’s third largest city, is often portrayed in Western media as a devastated urbanscape. But new Homs remains more or less as it was before the conflict began in 2011. The city’s wide streets are filled with traffic, shops are open, children go to school, and families visit restaurants and cafés.

There are two large but limited in scope areas of devastation in Homs: Baba Amr, where rebels and jihadists battled the army from 2012-13, and the Old City and adjacent neighbourhoods.

In these districts, damage is heavy, but total ruin is concentrated at certain locations. Voting in the presidential election took place in both places.

We drove into the Old City, passing the museum and other public buildings, and paused at the “new” clock tower, still erect, its black and white facade stained by warfare. It stands at the centre of a broad square surrounded by ruins.

The “old” clock tower was destroyed and has been replaced by an elegant lamppost bearing clock faces that actually tell time.

The Um Al Zanar Syriac Orthodox cathedral has been battered by fighting and scorched by a fire set by withdrawing insurgents, but is being restored by craftsmen with funds raised by the community.

This cathedral, the first in Christendom, traces its history to a church built 59 years after the crucifixion of Jesus. Here, the belt of the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus, was housed in a niche in the chapel next to the main church. The belt was hidden along with precious icons by parishoners before looters came.

Father Zahari Khazal, who is supervising restoration, is bitter about the torching of the church and its Bibles by a Syrian commander on orders from “outside”.

Father Zahari was a member of the committee that helped negotiate the withdrawal of the remaining 900 fighters and provided them with an escort to ensure their safety when they departed.

All the churches in the Old City were damaged and pillaged.

At the once elegant now shell-holed and pillaged Agha restaurant, located in an Ottoman mansion, the caretaker guides us to the bar that was used as an operations room and sanctuary by insurgents who not only left behind packets of medicine, clothing and bedding, but also a spent Turkish shell.

The restaurant’s owners plan to open as a café in a month to encourage people to return to the Old City.

Nearby on a shop front someone has posted a large photo of Assad and his wife Asma dining here.

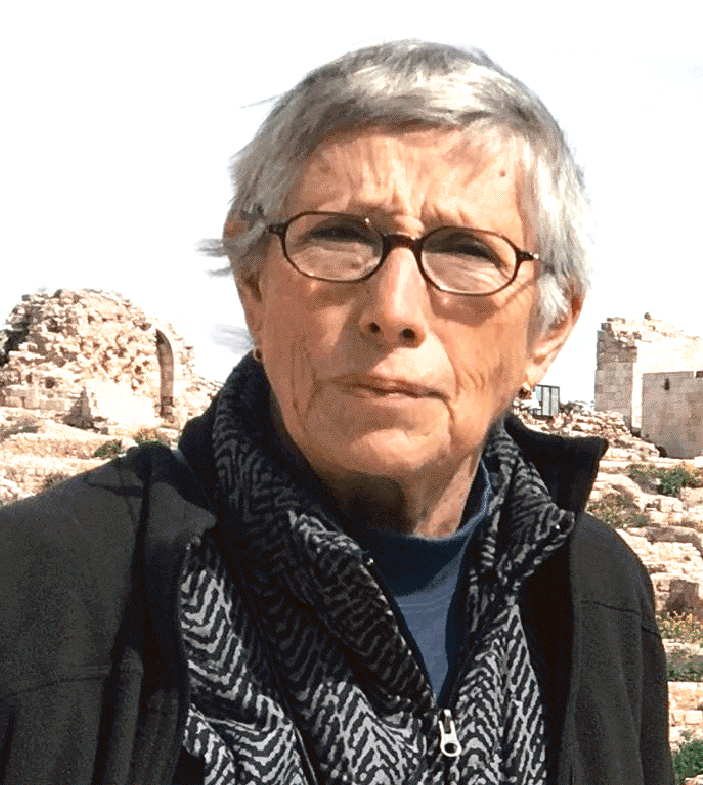

Syrian pilgrims and curious journalists make for the grave of Dutch Jesuit Father Franz van der Lugt, 75, slain by a masked gunman on April 7 as he sat in a chair in the courtyard of the monastery where he had lived for decades.

Dedicated to the people with whom he dwelt, he stayed on through the insurgent occupation, government siege and blockade, suffering privation and risking his life.

Plastic flowers adorn his tomb and the chair where he was shot after refusing to leave his home. No one knows who killed him or why.

The elegant black-and-white-striped, stone-built Khaled Ibn Walid Mosque with its silver domes was not spared in the fighting.

Built in the late 19th century by Ottoman Sultan Abdel Hamid on the site of earlier mosques, it was used as a base by insurgents, fired upon by the army and looted by fighters before they departed. They stole even the taps in the white marble fountain used by the devout to wash before prayers.

All places of worship have been victims of this terrible war. Nothing is sacred in Syria.