You are here

Iran’s guards using Trump’s victory to claw back power

By Reuters - Nov 21,2016 - Last updated at Nov 21,2016

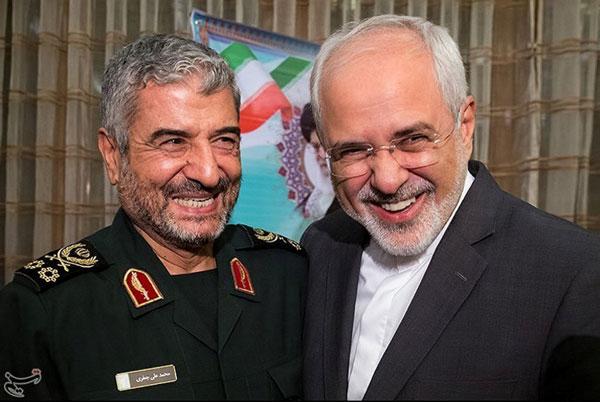

ANKARA — Donald Trump’s victory and the war on the Daesh terror group have given Iran’s hard-line Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) what it sees as a unique opportunity to claw back economic and political power it had lost.

Sidelined after a nuclear deal was reached with Iranian leaders and the administration of President Barack Obama and major nations, the IRGC is determined to regain its position in Shiite Iran’s complex governing structure.

Republican Trump said in the campaign that he would abandon the 2015 deal that curbed Iran’s nuclear ambitions in return for the lifting of economic sanctions. His tough stance, in contrast to Obama’s olive branch, is expected to empower hard-liners who would benefit from an economy that excludes foreign competition.

In addition, the Quds force, that conducts IRGC policies overseas, has played a successful and key role on the battlefields of Iraq increasing the Guards’ kudos at home.

“Trump and Daesh militants were gifts from God to the IRGC,” said a senior official within the Iranian government, speaking to Reuters on condition of anonymity like other figures contacted within Iran.

“If Trump adopts a hostile policy towards Iran or scraps the deal, hardliners and particularly the IRGC will benefit from it,” a former reformist official said.

Elected in a landslide in 2013 on a promise to end Iran’s diplomatic and economic isolation, pragmatist President Hassan Rouhani has struggled to reconnect Iran’s economy to world markets and to attract foreign investment.

Uncertainty over the nuclear deal, unilateral US sanctions, political infighting in Iran alongside complex regulations, labour issues and corruption have hampered a post-sanctions economic revival causing concern to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei who blames the government.

Sanctions benefitted IRGC

Deeply loyal to Khamenei, the IRGC was created by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, leader of the 1979 Islamic revolution. The IRGC first secured a foothold in the economy after the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War when the clerical establishment allowed them to invest in leading Iranian industries.

Involved in a wide range of businesses, from energy and tourism to car production, telecoms and construction, the IRGC’s empire grew by taking billions of dollars in projects vacated by Western oil companies because of sanctions imposed to curb the nation’s nuclear ambitions.

Trying to limit IRGC influence, Rouhani’s government stalled or cancelled some major projects with the IRGC, including a $1.3 billion deal with National Iranian Gas Co. in March 2014.

Under the nuclear deal, international sanctions were lifted in January opening up the Iranian economy, thereby threatening the IRGC power base. Now the Guards see an opportunity to lever back their position in the Iranian hierarchy.

“The IRGC will use Trump’s win to convince the clerical rulers to give them more political and economic backing. This is what they have been hoping for since the deal was reached,” said the senior government official, who declined to be identified.

“If Trump’s presidency scares away foreign investors from Iran, then it is the IRGC that will regain its economic power,” said a former reformist official close to Rouhani.

“More economic involvement of the IRGC means a riskier market for foreign investors. It will hinder Rouhani’s planned economic growth and will give more political power to the IRGC and their hard-line backers,” the reformist official added.

Guard against uncertainty

Senior members of the IRGC and its front companies remain under unilateral US sanctions for what Washington said was supporting “acts of terrorism”.

Anxious about losing economic power, the IRGC accused Rouhani of favouring foreign firms rather than domestic ones, demanding a bigger role in the economy and calling for implementation of Khamenei’s vision for a self-reliant Iran.

“The IRGC-linked companies cannot compete with the foreign firms. Therefore, they will want a limited presence for foreign firms in Iran,” said Tehran-based trader Mohammad Ali, adding: “Money means power.”

Foreign companies need an Iranian partner to do business in Iran, which for big projects often means firms controlled by the IRGC. Most of IRGC front companies are not formally owned by the Corps, but by individuals and firms linked to it.

The IRGC remains opaque to outsiders.

“The Guards have different layers. The roots of the IRGC are seasoned and senior commanders who idolise the supreme leader and are ready to sacrifice their lives for pillars of the revolution and have influence in political and overseas activities of Sepah [IRGC],” a retired IRGC commander told Reuters, declining to be named.

“Also there is another layer and not at the top that have been involved in business activities. They gained more economic power under former president [Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad.”

The future of the nuclear deal will have a direct bearing on IRGC military, political and economic ambitions and it is unclear if Trump will carry out his threat to abandon it.

During the campaign, Trump dismissed the deal as “one of the worst deals I’ve ever seen negotiated”. But Trump has in the past made contradictory statements so foreign governments are unsure how much of his rhetoric will be translated into policy.

Middle East political analysts expected the powerful clerical establishment’s political backing of the IRGC to harden in reaction to the uncertainty concerning a Trump presidency.

“The IRGC will gain more power at least until the dust settles after Trump’s win ... the atmosphere in Iran will be militarised because of more power that will be provided to the IRGC,” political analyst Hamid Farahvashian said.

“Uncertainty over Trump’s Iran and regional policies, Iran’s presidential election in May and economic hardship that might lead to street protests will force the establishment to give more power to the IRGC.”

It was the IRGC that suppressed student protests in 1999 and also silenced pro-reform protests that followed Ahmadinejad’s disputed re-election in 2009.

In rivalry with Sunni Saudi Arabia, Iran has fought decades of sectarian proxy war in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen and other regional countries. Quds Force commanders have been active recently on the battlefields of Syria and Iraq.

“The IRGC will adopt a more aggressive and tougher approach in the coming months,” the former reformist official said.

Western governments and Israel accuse the Quds Force of arming various militant groups in the Middle East.

“The Corps are in charge of preserving Iran’s national security and its overseas activities. So, having a threat like Daesh at our borders and the regional crisis make the Guards essential for Iran,” a senior Iranian security official said, on condition of anonymity.

“No matter who is the president in America or elsewhere, we will support our allies and our Guards will do that.”

Related Articles

ANKARA — President Hassan Rouhani and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei may have sharply ideological differences but the fragility of Ir

LONDON — A tough line from President Donald Trump has been met by a show of unity from both sides of Iran’s political divide, uniting hardli

DUBAI — Iranians yearning for detente abroad and greater freedoms at home have handed President Hassan Rouhani a second term, but the hardli