You are here

US scholar puts together pieces in attempt to rediscover ancient board games

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Feb 25,2020 - Last updated at Feb 25,2020

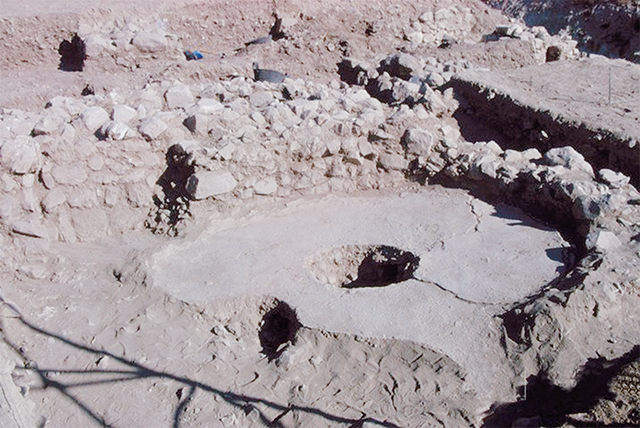

During the classical period, board games similar to mancala, senet, mehen and chess were played in the Mediterranean basin and Africa, according to Professor Emeritus Gary Rollefson (Photo courtesy of Gary Rollefson)

AMMAN — On a terrace high above the lower Wadi Al Hasa in central Jordan, two game boards were found at an archaeological site, shedding light on the prevalence of these forms of entertainment activities in ancient times, according to an American anthropologist.

During the classical period, board games similar to mancala, senet, mehen and chess were played in the Mediterranean basin and Africa, where their popularity continued into the Bronze Age, said Professor Emeritus Gary Rollefson.

“Origins of complex gaming remain debatable, but there is now a wealth of examples of analogous game boards that date from the Neolithic period in Jordan, Syria, the Sinai Peninsula and Iran,” Rollefson told The Jordan Times in a recent e-mail interview.

Prehistoric game boards were first recovered at Beidha, just a few kilometres north of Petra, Rollefson continued, adding that the game boards were made of local sandstone.

“Two complete game boards came from Ain Ghazal, near Jordan’s capital Amman. One in 1989 and the second specimen from the same site was recovered in 1996,” the scholar said.

Prehistoric archaeology suffers “serious deficiencies” when it comes to understanding past human activities and the social context in which they occurred, the professor said, adding that a major problem is the absence of sources, both material and written.

As a result, the collection of data might lead to the recognition of patterning that must be explained hypothetically, Rollefson said.

One striking aspect of the more than 45 Neolithic boards is the high number of broken specimens, the scholar pointed out, while only five are whole and intact. Of those five, two were later used as stones in building construction after their use as game boards ended, Rollefson said.

“It appears that most of the boards [almost 90 per cent] were not accidentally fragmented, but were intentionally broken. This suggests a possible cultic purpose for the boards, analogous to the treatment of clay human and animal figurines at Ain Ghazal, which were purposefully broken and discarded,” Rollefson said.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The settlement at Ain Ghazal Site is one of the largest Neolithic settlements known in the Near East and is situated on the western

AMMAN — Anthropologist Gary Rollefson’s nearly four-decade long research into the anthropology of prehistoric Levantine civilisations began

AMMAN — During the filed season in 1996 at Ain Ghazal on the north-eastern outskirts of Amman, the archaeological team discovered a rectangu