You are here

Temporary schools for a hopefully temporary situation: Young Syrian refugees find the right people to help them keep dreaming

By Muath Freij - Mar 12,2014 - Last updated at Mar 12,2014

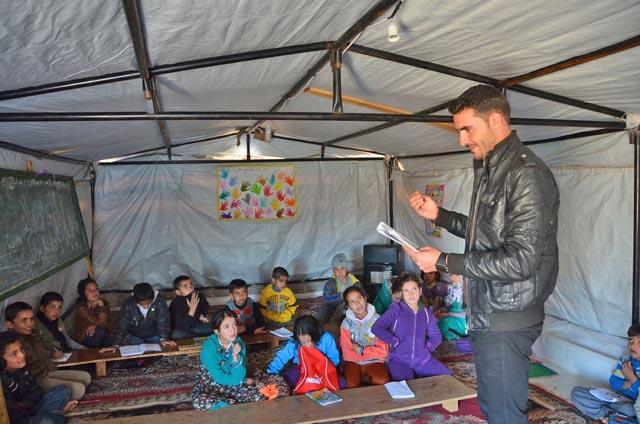

AMMAN/ JORDAN VALLEY — From his precious savings, Syrian Khaldoun Al Ahmad decided to spend JD20 to buy a tent and transform it into a school for fellow refugees at a makeshift camp located in the Northern Jordan Valley.

Although the 32-year-old teacher needs every dinar he can spare, he said he wanted to teach children because they are the future of Syria.

“These children have been displaced for years and they missed school for a long time. If no one pays attention to their education, the future of Syria will be lost,” Ahmad told The Jordan Times in an interview near the school.

Half of the Syrian refugees inside Jordan are children. Of these, around 87,000 are registered in public schools, according to UNICEF Communication Specialist Toby Fricker.

“Around 23,000 children are registered inside the Zaatari Refugee Camp for school. Obviously, it does not necessarily mean that they go to school daily but they are registered,” he told The Jordan Times in a recent interview at the UNICEF premises in Amman.

Several factors related to the three-year conflict in Syria made education either not important for refugees or hard to reach.

Manal Wazani, CEO of Save the Children Jordan (SCJ), noted that transportation is one of the main obstacles children face.

“Sometimes it’s difficult for Syrians to find means of transport because of financial hardships. In addition, some families do not send their children to schools because they are far from their tents,” she told The Jordan Times.

Ahmad noted that he launched his initiative because of distance issue.

Diana Siam, SCJ’s team leader psychologist, noted that the events families and their children witnessed back home have had a negative impact on their psychological side.

“Some families in the Zaatari Refugee Camp were reluctant to send their children far from their tents. Gradually they restored trust and are sending the young to school,” she told The Jordan Times in an interview on Tuesday.

Siam also noted some children who witnessed bombs while they were in schools in Syria did not have the courage to go to schools in Jordan.

“These children need time to embrace school again,” she added.

When Syrian refugees first arrived in the Kingdom, the last thing they cared about was education, according to Wazani.

“They were looking for food, clothing and medical services. One of our tasks was encouraging families to enrol their children in schools,” she added.

SCJ works on raising Syrians’ awareness towards the importance of education, registering students at the schools and distributing books and stationery.

She also pointed out that the capacity of schools is one of the obstacles children face.

Fricker pointed out that there are 78 schools that are applying the double shift system for Syrian children in areas that witness a great number of Syrian refugees such as Mafraq, Ramtha and Amman.

“Syrians go to these schools in the afternoon. This is an emergency measure applied to cope with the great number of Syrian children in Jordan,” he added.

The international worker noted that one of the key challenges is to make sure that children are actually attending the schools.

“We work with the Ministry of Education to make sure that there are enough teachers and that they are qualified,” he added.

The UNICEF official noted that they work with the Ministry of Education in terms of teachers training.

Luckily, he said, Jordan is a huge producer of teachers, but one of the challenges is that some of the teachers are either part time or substitute teachers, and in some cases they are not as qualified as others.

He said it is hard for teachers to work with children coming from a war zone. “We are trying to work with the teachers to increase their ability to provide quality education to these children,” he added.

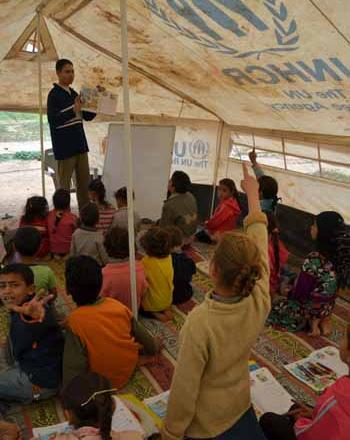

In camps, Jordanian teachers come on a daily basis to teach in schools and are assisted by Syrian teachers.

One of the key negative effects is child labour, said a volunteer Syrian teacher, who identified himself as Majed.

The Syrian teacher who, like Ahmad, turned a tent into a makeshift school for refugee children in Amman, noted that he found difficulty persuading families to send their children to the school because they wanted them to work.

A Syrian refugee, Um Karam, a mother of six, noted that her 13-year-old son used to study at Ahmad’s school but she forced him to leave it and take a job on a farm, working five hours a day to get paid JD1 per hour.

Fricker described child labour as a “big problem”.

“Child labour exists both inside and outside the Zaatari. People who are living outside the camp are struggling to pay the rents, and unfortunately children present an economic opportunity as they can get a job at a coffee shop or on farms in the Jordan Valley,” he added.

He noted that if children have to work, they provide them with some form of “informal” education.

Meanwhile, a considerable number of Jordanians and Syrians have volunteered to teach Syrian children especially in the makeshift camps such as Ahmad and Majid, according to Wazani.

UNICEF facilitates the process by providing them with stationery, she added.

“We are going to update manuals that teach life skills,” Fricker added.

Such initiatives have provided nine-year-old Sidra Al Omar with the chance to keep dreaming as she attends Ahmad’s school.

The Hama-born girl wants to become a doctor and she is happy with the “rich and different” learning experience.

Siam knows what the young refugee is talking about. The volunteers, whether Jordanian, Syrian, or international workers, are compassionate people who are there to help and to give.

Schooling in Zaatari

•In September 2012, the first school was established in the Zaatari Refugee Camp.

•Around 1,000 students were registered then.

•There are 12 schools in the camp now, distributed equally among four “administrative units”.

•Around 23,000 students are registered in these schools.

•Of these, around 13,000 students are actually attending classes.

Related Articles

With a lack of entertainment options in the makeshift refugee camp in the Jordan Valley, Khaldoun Ahmad's initiative was to become the saving grace for Syrian children learning to settle into Jordan.

AMMAN — Chairperson of Save the Children Jordan (SCJ), HRH Princess Basma on Tuesday visited programmes that support Syrian refugees living

When 10-year-old Omran Taqi arrived in Amman with his family, the activity he missed the most was going to school.