You are here

Symbols of the Middle East: Decoding cultural, functional significance of Wusum marking system

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jan 31,2024 - Last updated at Jan 31,2024

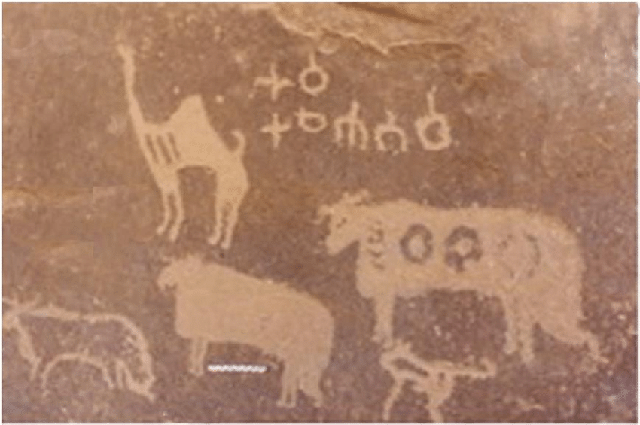

Camel and sheep with wasum, or tribal symbols, marked on their bodies seen on petroglyps (Photo of Majeed Khan)

AMMAN — Across the Middle East, multiple Bedouin groups use a system of markings called Wusum (singular: Wasm), frequently encountered in the shape of animal brands or petroglyphs, as well as lines and dots, or a combination of the two, and sometimes take on geometric shapes such as circles and squares, noted Koen Berghuijs from Leiden University in The Netherlands.

“Comparable to the concept of a signature, Wusum operate on and refer to various levels of different but closely intertwined modes of social organisation, including families and tribes,” Berghuijs explained, adding that Wusum are frequently encountered in archaeological surveys throughout the Near East but have so far not received much scholarly attention.

Wusum petroglyphs can be found in Socotra, Yemeni, Saudi deserts and the Levant.

According to Berghuijs, for most archaeologists, Wusum form a type of petroglyphs that appear to be idle derivatives of modern-day camel brands and, because of that, are deemed the result of bedouin pastime practices not worthy of further investigation.

“In general, all that can be said about Wusum is that their meaning is open to many interpretations and in the majority of cases, their significance goes beyond being merely indicative,” the Dutch scholar underlined.

During his pioneering field research in oral poetry and narratives from central and southern Nejd, Dutch scholar and diplomat Marcel Kurpershoek documented a bedouin sheikh’s perspective on the nature of contemporary Wusum: According to him, Wusum is like a personal name or a family name and it distinguishes tribe from tribe.

Nowadays, Wusum indeed occur mainly as animal brands to indicate ownership; examples of such brands can still be observed among camel herds in the region, Berghuijs said, adding that in the 19th century, however, Wusum were utilised in a much wider range of contexts and appear to have played important roles in bedouin societies.

“Ethnographic sources, oral traditions and travellers” accounts not only feature a rich variety of marking applications but also demonstrate the economic and sociopolitical dimensions of Wusum,” Berghuijs underlined, adding that the marking practices recorded by these early explorers and scholars demonstrate that Wusum were indelibly connected with various aspects of the bedouin life, including territoriality, access to natural resources and matters of identity.

The first European to note the existence and use of Wusum as animal brands was a famous Swiss explorer, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt.

During his travels in the deserts of Arabia and Syria between 1810 and 1812, Burckhardt observed that: “All the Bedouin camels are marked with a hot iron, that they may be recognised if they straggle away, or should be stolen. Every tribe and every taifé, or family of a tribe, has its own particular mark. This is generally placed on the camel’s left shoulder or its neck.”

Not only was the shape of the wasm indicative of the associated social group, but also its position on the animal in question. Common locations included the camel’s nose, forehead, cheeks, neck, shoulders, hips, legs and buttocks, Burckhhardt testified.

Wusum marking practices formed an important part of 19th century bedouin life, stressed Berghuijs, noting that the markings, whether applied to animals or burials, were simultaneously physical representations of abstract sociopolitical relations and identities; a direct link with mythical ancestors from which hereditary status was derived; and expressions of (temporary) claims to resources, all bound together in a single wasm.

“The tentative of dating of Wusum petroglyphs from the Jebel Qurma region offers a new way of identifying [post-] Ottoman era human presence and activity in the area, and perhaps the Near East at large,” Berghuijs explained.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The 12,000 years of human occupation in the Arabian Peninsula are illustrated through the diverse markings left by various civilisat

AMMAN — The name “Bedouin” is derived from the term for nomadic desert or steppe dwellers (badawa).

AMMAN — “The question of why there are no gazelles represented in the petroglyphs [designs pecked into a stone surface] remains puzzling,” s