You are here

Serbian Egyptologist reviews scorched earth policy in ancient warfares

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jan 18,2018 - Last updated at Jan 18,2018

Photo courtesy of Uros Matic

AMMAN — During the New Kingdom, Egypt “slowly but surely” established its control over southern Levant through a series of military campaigns in this region, starting from the first king of the 18th dynasty, Ahmose, according to a Serbian archaeologist and Egyptologist.

“Although, local rebellions occurred every now and then, by the Amarna period [1353 - 1336 BC] the region was controlled by Egypt through vassal relations with the local rulers who received support from the Egyptian king in situations of local crisis or danger”, said Uros Matic, who is currently at the Institute for Egyptology and Coptic Studies of the University of Münster, Germany.

In the Ramesside period Egyptian military becomes more physically present in the region, while this control was gradually lost at the middle to the end of 12th century BC, he added in a recent e-mail interview for The Jordan Times.

The policy of scorched earth was not an invention of the modern warfare: “According to available textual and iconographic attestations for destruction of landscape Egyptian military utilised numerous strategies in siege of Syro-Palestinian cities”, the scholar said, noting that among these are burning and destroying towns, settlements and villages, cutting down grain, barley, fruit trees and plantations.

Furthermore, scholars have to be careful when attributing real historical background to each of the attestations they have at hand because many of the statements on the destruction of enemy landscape are stock-phrases and are highly rhetorical, Matic explained.

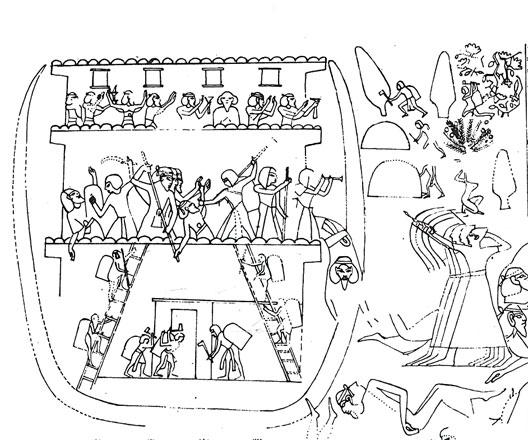

“Nevertheless, the fact that these actions are used in building stock-phrases and that in some cases the cutting down of trees surrounding an enemy fort is depicted [Siege of Tunip, Ramesses III, Medinet Habu, North wall between the 1st and 2nd pylons, outside], permits us to suppose that in some cases these actions were taken,” the archaeologist elaborated.

During the reign of Ahmose New Kingdom military campaigns in Palestine are monumentalised on his temple reliefs in Abydos, he underlined, stressing that later on there are some fragments of temple reliefs of Thutmose II, Thutmose III and Amenhotep II “indicating that temples were decorated with scenes of war also later on”.

“We know from the Memorial temple built for Tutankhamun by Ay that the programme of these war scenes did not drastically change and it continues into the Ramesside period [1189-1077BC],” Matic underlined.

“The images in question present us with an ideological binary opposition between the victorious king of Egypt and his army and the defeated conquered peoples who are depicted as cowardly, weak and submissive,” Matić explained, adding that the king in most cases occupies the edge of the scene where he is depicted as the largest figure (super-human) riding in his chariot and shooting the enemies with his bow.

“However, there are also motifs such as an enemy climbing a tree but being taken down by a bear or enemies hiding among the trees around the fort which some authors interpret as being narrative snapshots of stories now lost to us,” he said.

Regarding the treatment of vulnerable civilian populations, “One interesting fact is that during the New Kingdom foreign women and children are not depicted as victims of violence in war, neither in text nor in image. This can be interpreted as a consequence of gender framed decorum in which proper soldiers are not considered to be those being violent to the opposite gender,” the researcher explained.

According to Matic, there is a difference in depiction of different enemies which seems to be based on Egyptian hierarchy giving privilege to settled peoples such as the inhabitants of Syria-Palestine in contrast to unsettled people such as the inhabitants of Nubia.

“Scorched earth strategy against Egyptian enemies in southern Levant is not particularly well attested as the majority of attestations we have point to its usage in northern Syria-Palestine,” Matic highlighting, adding that this was surely because northern Syria-Palestine region was continuously rebellious and was hard to establish control over it.

Matic also sees the problem in older interpretations of destruction levels on various Levantine sites of the 12th century BC as being destructions caused by the Sea Peoples.

“Nowadays, we know that the reality was much more complex and that some of these destructions can be attributed to earthquakes, locally produced fires or local agents,” he underlined, noting that “We also have to bear in mind that total destruction of enemy cities, although being a motif in Egyptian ideologically coloured texts, was not in the interest of the Egyptian state”.

Fortifications and infrastructure were important for further functioning and control of the region either by local vassals or Egyptian governors present there, he stated.

Furthermore, activities such as cutting down trees or destroying various crops, although attested in Egyptian textual and iconographic sources, can hardly be detected archaeologically, Matić noted.

Even if they would be detected it would be hard to argue with certainty that the Egyptian army was responsible, he concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — A rescue excavation by the Department of Antiquities (DoA) of Jordan has uncovered a basalt statue in the forum area near the Roman

CAIRO — Egypt's antiquities authority says it has found the ancient tomb of King Thutmose II, the first royal burial to be located since the

AMMAN – Chariots played a prominent role in traditions for different civilisations.