You are here

Sahab holds archaeological treasures — Jordanian scholar

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Oct 14,2019 - Last updated at Oct 14,2019

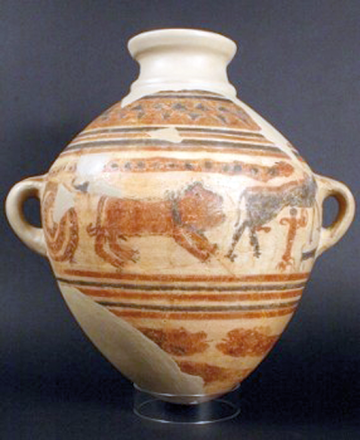

An Iron Age carinated incense burner from Sahab, circa 1,000-700 BC (Photo courtesy of Barakat Gallery)

AMMAN — Sahab represents one of the largest Jordanian archaeological sites in the transitional zone between the highlands and the desert, said a Jordanian archaeologist.

The city, located some 12 kilometres southeast of Amman, is on the modern and ancient road to the desert castles of the Early Islamic period, including Muwaqqer, Kharraneh, Quseir Amrah, Azraq and others, Professor Emeritus Moawiyah Ibrahim told The Jordan Times in a recent interview, adding that Sahab’s location was “evidently a lucrative choice”.

The modern town of Sahab was founded on the ancient tell (mound) and spread to the surrounding area, destroying major parts of the ancient settlement in the process, the archaeologist said.

He noted that the highest point of the mound is about 22 metres above the western plains.

“The area around Sahab is well cultivated, with the actual desert about 15 to 20 kilometres to the east,” Ibrahim continued.

According to the archaeologist, the excavations at the site were considered a salvage operation, and continued for a few years.

“It was probably the largest excavation project to be undertaken and sponsored by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities (DoA). Several members of this department were trained at the site,” Ibrahim stressed, adding that the budget for the excavations and participating members was very limited.

Sahab was occupied from the Late Neolithic/Chalcolithic period (5th and 4th millennia BC) to the Late Iron Age (6th century BC), Ibrahim said, adding that the site was apparently abandoned until the Medieval Arabic period (11th-13th century AD), as evidenced by Ayyubid/Mamluk pottery shards.

“Another occupational gap ran from the 13th century to the 19th century, when the present inhabitants moved to the site,” he said.

Sahab was largest in area during its earliest period of habitation, when it supported itself with extensive agriculture and produced “an abundance of food”, said Ibrahim, noting that this agricultural abundance is demonstrated by the large number of storage facilities inside the houses and in courtyards.

“Some of the courtyard storage structures were huge, measuring around four metres in diameter, and the pit structures suggest that Sahab’s inhabitants anticipated occasional periods of poor agricultural yield that could be offset by a long-term storage strategy,” the expert said.

The way these storage pits are arranged within house units may suggest that large families were living in each quarter of the site, he added.

“Unfortunately the entire archaeological site is located under the modern houses of Sahab. The centre of the site was preserved for future investigations to be carried out by the DoA in collaboration with archaeologists interested in the represented periods and the region,” Ibrahim said.

Regarding the earliest occupation of the site, the professor said that in 1984, survey scholars could not identify any settlements that directly preceded Sahab.

“It is clear, however, that the inhabitants of early Sahab were experienced farmers and must have had a good knowledge of building techniques, as well as of the manufacturing of pottery, stone vessels, flint implements and other stone tools,” Ibrahim concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The Jabal Qurma Archaeological Landscape Project started in 2012, with extensive field surveys and excavations in the basalt desert

AMMAN — Cave dwelling was practised on a large scale in Sahab, located 12 kilometres southeast of Amman, during the Chalcolithic period and

AMMAN — A number of objects have been excavated from Tell Zira’a (located around five kilometres southwest of ancient Gadara) by the German