You are here

French scholar mulls over scarcity of baths in Nabataean Petra

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Dec 24,2017 - Last updated at Dec 27,2017

Khubtah baths located on a cilff edge in Petra (Photo courtesy of Thibaud Fournet)

AMMAN — Until now, very little was known about public baths in Petra, according to a French architect affiliated with Ifpo who developed a research project in the field of Greek, Roman and Byzantine urbanism and architecture.

In 2005 the American excavation of the “Great Temple” had revealed a well-preserved bath building, attesting the presence of this kind of public facilities during Roman-Byzantine time, Thibaud Fournet noted.

“Before that, the only known baths were private, in Roman villas of Zantur and Wadi Musa,” he continued, adding that it was “a meagre record for a place like Petra, especially if compared to other Near Eastern ancient cities”.

However, since 2010 surveys and excavations revealed four other baths, boosting our knowledge on the bathing practices in Petra, Fournet stressed in a recent interview for The Jordan Times.

“First, the architectural study of the remains excavated by Adnan Shiyyab and students from the Al Hussein Bin Talal University (Maan/Wadi Musa), allowed to identify a large field of ruins in the centre of the city as a monumental bath building,” he elaborated, highlighting that those remains (mistakenly called “Byzantine tower” on some city maps), visible from the outside by thousands of visitors between the colonnaded street and the Byzantine church "are in fact only the tip of an architectural iceberg".

This monument, with hot pools, heating system, lavish marble pavement, decorative apses and courtyard, is very similar to other huge imperial baths known in almost all cities by the end of the Roman period, the French expert underlined.

“This discovery helps also to figure out how much the Petra city centre was transformed in Roman times,” the scholar said.

Another bath was discovered in 2012 by the French team in a spectacular location, on the very edge of a cliff, on top of Jabal Khubthah.

“Their excavation and architectural study in 2015-2017 enable a complete reconstruction,” Fournet claimed. “The main phase of this building is late Roman,” he explained, “but stands atop earlier remains”.

The strong similarities with the Umm Al Biyara baths (discovered in 2011 by the International Umm Al Biyara Project) lead researchers to propose for Khubthah’s bath a similar chronology: first phases on the beginning of the 2nd century AD, transformation/reconstruction up to the 4th century AD, the French scholar underscored.

Moreover, the breathtaking location of both buildings, on the edge of the cliff, overhanging the valley by circa 300 metres, was "deliberately decided".

“The ‘last’ bath building was discovered in 2014 during the French survey of Sabra, a satellite hamlet of Petra located 7km southwest of the city centre, in a wadi connecting Petra to the Wadi Araba caravan trail,” Fournet noted.

This remote place, known since the 19th century for its well-preserved theatre, had never been properly explored by archaeologists, according to the French researcher.

“The topographic and archaeological surveys revealed, beside a temple and many other architectural remains, a very well-preserved bath-building, located just beside the temple,” he emphasised, adding that it is partly exposed by the wadi floods, so a complete architectural interpretation was possible.

The bath consists of a porticoed courtyard, a "frigidarium" (cold room) and a set of heated rooms, fitted with hot plunge, he pointed out.

Two examples in the Nabataean sphere, in Wadi Ram and Dharih (recently excavated by Caroline Durand from Ifpo), illustrate the same association of temples with bathhouses. “Those were probably used by pilgrims for ablution before entering the sacred precincts,” Fournet speculated.

Both baths were built between the last quarter of 1st century AD and the beginning of 2nd century AD, during a refurbishing of sanctuaries, he said.

No technological barrier (Nabataeans were known as masters in water management) can explain the lack of bath buildings in Petra in the previous two centuries, the French architect explained, adding that it looks impossible, considering the strong and well-known ties between Petra and Alexandria, that Nabataean society or rulers had no knowledge of the massive bath-housing boom in Greco-Roman Egypt observed between 1st century BC and early 1st century AD.

“In the same way, Nabataean kings were aware of the luxurious bathhouses built within the Herodian kings palaces at the gates of their state in Masada or Machareus at the same period,” Fournet stated.

The explanation justifying this absence of baths in Nabataean Petra must be cultural: Collective bathing practices were apparently rejected by Nabataeans, who have drawn an invisible frontier in the dissemination of a Mediterranean shared culture of collective bath between the 1st century BC and the end of 1st century AD, he underlined.

“Most baths in Petra appear precisely between the end of 1st century AD and beginning of 2st century AD, exactly around the time of the Roman annexation in 106 AD, when Nabataean Kingdom turns to the new Roman Province of Arabia,” Fournet concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The professor of Pantheon-Sorbonne, Francois Villeneuve, has worked for decades in the region and some of his project included the N

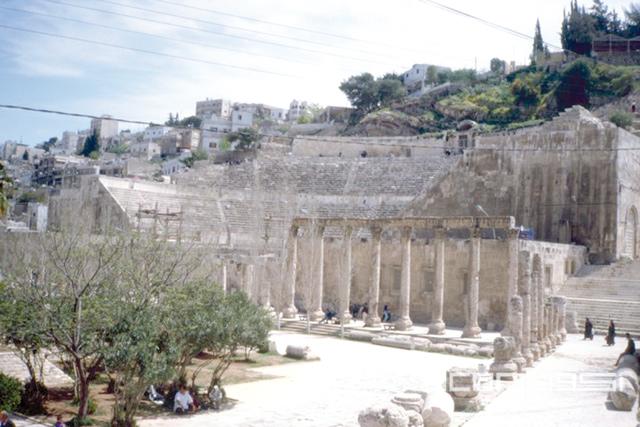

AMMAN — Following the intervention of Roman general Pompey the Great (106 BC-48 BC) in the Levant, Gerasa (Jerash) and Philadelphia (Amman)

AMMAN — After excavation of the Petra Church, a group of researchers worked on two churches on the higher slope — the Ridge Church and the B