You are here

Archaeologist highlights link between contemporary and Bronze-Age olive oil production

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Oct 31,2019 - Last updated at Nov 03,2019

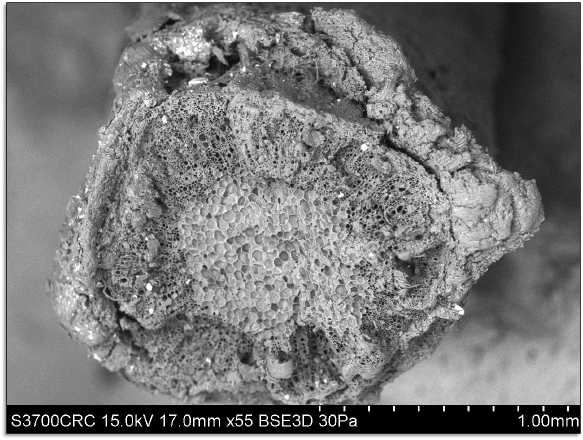

Excavation at Khirbet Ghozlan in Wadi Rayyan (Photo courtesy of Adam Carr)

AMMAN — During the Bronze Age, olives became “an integral part of Jordanian social fabric”, having been domesticated in the Levant, then in Greece, before moving westward to Spain, according to an Australian archaeologist.

“The Mediterranean has optimal conditions for olive growth — temperatures are hot, dry summers, cool winters — but anything that drops below -7°C is no good for olives,” said scholar James Fraser at a lecture titled “The Archaeology of Olive Oil”, held at the American Centre of Oriental Research in Amman on Wednesday.

He added that there are 1,200 domesticated species of olives in the Mediterranean basin.

“The process of harvesting olives has remained more or less the same up till now,” he noted.

Fraser leads the Khirbet Ghozlan Excavation Project, and investigates an ancient olive oil “factory” in Wadi Rayyan that is about 4,500 years old. He is particularly interested in how the continued production of high-value liquid products such as olive oil helps illuminate rural responses to the collapse of Jordan’s earliest cities between 2600 and 2000 BC (the Early Bronze IV period).

“The site of Khirbet Ghozlan lies in the eastern escarpment of the Jordan Rift Valley and dates back to the Early Bronze IV period,” the scholar said.

He highlighted the enclosure wall circling the settlement, despite its area of only 4 dunums.

“Why enclose such a small site?” he asked.

In 2017, the British Museum commenced excavations to test the hypothesis that Khirbet Ghozlan was an ancient olive oil factory, Fraser explained, and as such, it likely served as a “specialised production centre” for upland horticultural crops such as olives, and was enclosed to protect seasonally produced caches of high-value commodities such as oil.

“Such sites were used just for the production of olive oil,” he stressed, noting that the economic implications of this industry are “profound”, as this period is characterised as a rural ‘Dark Age’ between the collapse of the region’s earliest urban centres in 2600 BC, and their rejuvenation as a mosaic of Canaanite city-states around 2000 BC.

Although communities of this period are thought to have reverted to simple forms of agro-pastoral subsistence, the excavations at Ghozlan suggest a complex rural economy, in which the production of olive oil was reconfigured within local settlement networks in niche environmental zones.

“The best analogies for understanding the archaeology of this 4,500-year-old factory are the small olive mills that are producing oil around Jordan at the moment,” Fraser underlined, adding these factories are closed for most of the year, and only open for harvest in October-November.

“The people who pressed olives at Khirbet Ghozlan seem to have worked the site seasonally in exactly the same way — but 4,500 years before,” Fraser concluded.

Related Articles

IRBID — Enclosed sites were specialised processing centres for the cultivation and production of olives and olive oil in ancient times, note

AMMAN – The Mediterranean diet has included olives and olive oil from the Bronze Age until modern times.

AMMAN — An enclosure wall that protected three buildings at Khirbet Um Al Ghozlan in Wadi Rayan, some 14 kilometres west of Ajloun, in