You are here

‘Stranded in a web of immobilising devices’

By Sally Bland - Jan 07,2018 - Last updated at Jan 07,2018

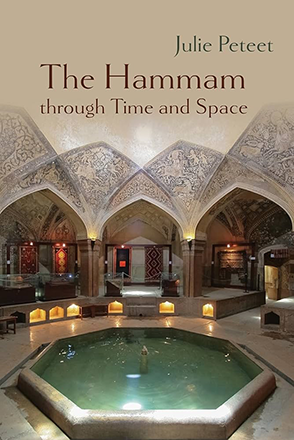

Space and Mobility in Palestine

Julie Peteet

US: Indiana University Press, 2017

Pp. 239

In her newest book, anthropologist Julie Peteet analyses the closure and separation regime, imposed by Israel on Palestinians under occupation, from every possible angle — moral, human, social, economic, legal, political, gender, corporal and psychological. Based on almost a decade of research and first-hand observation of the Wall, closed-off villages, curfews, identity card and permit requirements, checkpoints, terminals and segregated roads, she examines “the intersection of mobility and space, looking specifically at how access to space and thus to mobility devolve from racialised categories of ethnicity, religion and nationality”. (p. 2)

Peteet’s mode of analysis is relational, allowing her to draw sharply defined conclusions as to what exactly Israel wants with this system, and how it impacts on Palestinians’ daily lives and their political future. Simply put, whenever the space available to Israelis expands, that available to Palestinians shrinks. “In this context, time, like space, is decidedly relational as well as polyrhythmic. Piece by piece, an infrastructure that immobilises Palestinians and enables Israelis to move with relative ease and speed has taken shape.” (p. 144)

With Israel, Jerusalem and much of the West Bank mainly closed off to most Palestinians, they are not only separated from Israelis, but also from each other, and confined to limited enclaves, Gaza being the extreme example. “Palestinians are simultaneously locked in and locked out, stranded in a web of immobilising devices.” (pp. 63-4)

The book shows with multiple examples how this lack of mobility constricts and sometimes rules out Palestinian access to jobs, education, health care, political organising, and even their own land, and highlights the less obvious effects, such as the disruption of family and social ties — and of peace of mind. As much as the closure system seems highly regimented with strict rules as to where and how one can go, what permits are needed, etc., it is also unpredictable. Never knowing if a checkpoint will be open, or how long one will have to wait, wreaks havoc on daily schedules and plans, and has caused the death of patients seeking medical care. Indeed, a new form of control has been instated: “Control through the creation of calibrated chaos, the changing of rules and procedures with no warning or explanation, is enacted daily at checkpoints and in applying for permits… Unpredictability is the new norm.” (p. 38)

So is interminable waiting. This reinforces the perception that closure is not so much about security, as a form of collective punishment.

Much has been written about the Wall and other aspects of closure, but “Space and Mobility in Palestine” distinguishes itself by placing this system in a historical, regional and global context. Closure is framed as the current phase of the Israeli settler-colonial project in Palestine. In the post-Oslo period, Israel has eyed the chance to control all the land and resources of historical Palestine, but must grapple with the demographic issue. By making Palestinian lives so difficult, even impossible, Israel hopes to push them to emigrate, enacting gradual, “voluntary”, ethnic cleansing. “In essence, Palestinians inhabit a prison from which they are encouraged to escape.” (p. 9)

Enclosed and basically abandoned in their scattered enclaves, Palestinians resemble other “unwanted” population groups the neoliberal world over. Peteet compares the fortified Israeli colonies to gated communities, which are “flourishing globally as elites and states partition and barricade space in an attempt to exclude and lock out the anticipated violence of the have-nots, cast alternatively as criminals or terrorists”. (pp. 61-2)

She compares and contrasts the Palestinian situation with that of Native Americans, Afro-Americans under Jim Crow laws and today’s mass incarceration system, and apartheid South Africa.

Regionally, Peteet draws parallels to the reorganisation of space according to sectarian lines as happened in Iraq in the wake of the US invasion, in Lebanon during the civil war and most recently in Syria.

Though elements of the closure regime were put in place in the 1990s, Peteet points out that its development into a totalising system corresponded with the US-proclaimed “war on terror” and Israel’s enhancement as a high-tech “anti-terror” arms and security equipment supplier and trainer in the global arena. With its arms industry flourishing like never before, Israel has less interest in entering into Arab markets or peace. Conflict management has become the order of the day. By bringing in these regional and global parallels, Peteet sets the ever-growing overlap between Israeli and US strategies in relief.

Perhaps most importantly, Peteet gives voice to the Palestinian perspective: how coping with closure affects their lives and their thinking, how they analyse Israel’s aims, what they expect in the future, and what possibilities they see for resistance. To get this perspective, Peteet not only interviewed scores of West Bank and Jerusalem Palestinians, she travelled with them from one town and village to another on trips made long and arduous by having to circumvent settler-only spaces and roads. She waited with them at checkpoints, and attended protests against the Wall and land confiscation. Extensive quotes from those she interviewed and her first-hand impressions are interspersed throughout the text, adding vitality, authenticity and a deeply human dimension to her incisive analysis.

Related Articles

Allof anthropologist Julie Peteet’s previous books have focused on Palestine and Palestinian refugees, but her newest volume examines a phenomenon common throughout the Mediterranean region: the hamman, often referred to, though misleadingly, as the Turkish bath.

The General’s Son: Journey of an Israeli in PalestineMiko PeledUS: Just World Books, 2012Pp.

Gaza as a MetaphorEdited by Helga Tawil-Souri & Dina MatarLondon: Hurst & Company, 2016Pp.