You are here

Oldest human relative walked upright 7 million years ago

By AFP - Aug 30,2022 - Last updated at Aug 30,2022

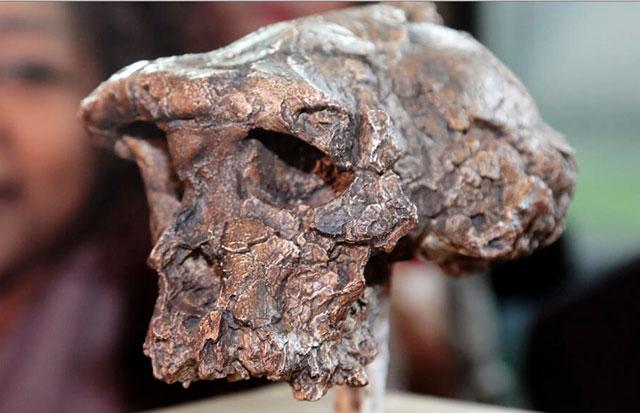

The partial skull of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis dubbed “Toumai”, which was discovered in Chad in 2001 (AFP photo by Jacques Demarthon)

PARIS — The earliest known human ancestor walked on two feet as well as climbing through trees around seven million years ago, scientists recently said after studying three limb bones.

When the skull of Sahelanthropus tchadensis was discovered in Chad in 2001, it pushed back the age of the oldest known representative species of humanity by a million years.

Nicknamed “Toumai”, the nearly complete cranium was thought to indicate that the species walked on two feet because of the position of its vertebral column and other factors.

However, the subject triggered fierce debate among scientists, partly due to the scarcity and quality of the available bones, with some even claiming that Toumai was not a human relative but just an ancient ape.

In a study published in the Nature journal, a team of researchers exhaustively analysed a thigh bone and two forearm bones found at the same site as the Toumai skull.

“The skull tells us that Sahelanthropus is part of the human lineage,” said paleoanthropologist Franck Guy, one of the authors of the study.

The new research on the limb bones demonstrates that walking on two feet was its “preferred mode of getting around, depending on the situation”, he told a press conference.

But they also sometimes moved through the trees, he added.

‘Not a magical trait’

The leg and arm bones were found alongside thousands of other fossils in 2001, and the researchers were not able to confirm that they belonged to the same individual as the Toumai skull.

After years of testing and measuring the bones, they identified 23 characteristics which were then compared to fossils from great apes as well as hominins — which are species more closely related to humans than chimpanzees.

They concluded that “these characteristics are much closer to what would be seen in a hominin than any other primate”, the study’s lead author Guillaume Daver told the press conference.

For example, the forearm bones did not show evidence that the Sahelanthropus leaned on the back of its hands, as is done by gorillas and chimpanzees.

The Sahelanthropus lived in an area with a combination of forests, palm groves and tropical savannahs, meaning that being able to both walk and climb through trees would have been an advantage.

There have been previous suggestions that it was the ability to walk on two feet that drove humans to evolve separately from chimpanzees, putting us on the path to where we are today.

However, the researchers emphasised that what made Sahelanthropus human was its ability to adapt to its environment.

“Bipedalism [walking on two legs] is not a magical trait that strictly defines humanity,” palaeontologist Jean-Renaud Boisserie told the press conference.

“It is a characteristic that we find at the present time in all the representatives of humanity.”

Our ‘bushy’ family tree

Paleoanthropologist Antoine Balzeau of France’s National Museum of Natural History said the “extremely substantial” study gives “a more complete image of Toumai and therefore of the first humans”.

It also bolstered the theory that the human family tree is “bushy”, and was not like the “simplistic image of humans who follow one another, with abilities that improve over time”, Balzeau, who was not involved in the research, told AFP.

Daniel Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University, said in a linked paper in Nature that the study’s “authors have squeezed as much information as possible from the fossil data”.

But he added that the research will not offer “full resolution” of the debate.

Milford Wolpoff, a paleoanthropologist at the US University of Michigan cast doubt on whether Toumai is a hominin, telling AFP that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”.

The study was carried out by researchers from the PALEVOPRIM palaeontology institute, a collaboration between France’s CNRS research centre and Poitiers University, as well as scientists in Chad.

Guy said the team hopes to continue its research in Chad next year — “security permitting”.

Chadian palaeontologist Clarisse Nekoulnang said the team was “trying to find sites older than that of Toumai”.

Related Articles

MAROPENG, South Africa — Palaeontologists in South Africa said on Monday they have found the oldest known burial site in the world, containi

PARIS — Our ancestors were making tools out of bones 1.5 million years ago, winding back the clock for this important moment in human evolut

PARIS — The drummers puff out their chests, let out a guttural yell, then step up to their kits and furiously pound out their signatur