You are here

Driven by love or moved by fate?

By Sally Bland - Mar 29,2015 - Last updated at Mar 29,2015

Chaos of the Senses

Ahlem Mosteghanemi

Translated by Nancy Roberts

London: Bloomsbury, 2015

Pp. 302

In “Chaos of the Senses”, Algerian writer Ahlem Mosteghanemi tells the story of a great love (or loves), with a tantalising twist. The man with whom protagonist and narrator Hayat falls in love is a character in a short story that she has written.

Soon after she completes the story, he enters her real life and begins “writing” her: It is he who almost single-handedly shapes their relationship. Her passion for him thrusts her into a glorious “chaos of the senses”, but a negative type of chaos is also emerging.

The novel is set in 1991, as Algeria’s political conflicts escalate into civil war, and Hayat moves between her hometown, Constantine, and the capital.

Having a character enter an author’s real life blurs the border between fiction and reality, between writer and text, and, implicitly, between Hayat and Mosteghanemi, infusing the book with an ambiguity which applies both to the political situation and the love story. Mosteghanemi plots her story carefully to fuse the personal and the political, and is skilful enough to maintain the ambiguity to the very last line.

Although Hayat seems very independent, one soon sees that she is mentally buffeted about and torn between the contrary images of four men in her life: Her father, long dead, was a great hero and martyr of the Algerian liberation struggle.

Her husband is a military officer in the regime which, by now, is only nominally the successor of this legendary struggle. Her brother, Nasser, named after the late Egyptian president and symbol of Arab nationalism, has joined the Islamists who are targeted by her husband’s forces. Her lover stands somewhere in between; as a journalist, he could be killed by either side.

With this constellation of characters, Mosteghanemi positions herself to weave pivotal moments of Algerian history, and different types of Algerians, into the novel’s love story. While Hayat has too much emotional depth and intellect to function as a mere symbol, she does seem intended to stand for Algeria, now at a crossroads.

Raised on “patriotic nostalgia”, she married a man with whom she has little in common, because his “political duties and military rank… hearkened back to the glory days of an Algeria of which I’d always dreamed”. On the other hand, “he’d given me no freedom, nor had he left any space in my life into which anyone could steal”. (p. 27)

In this context, Hayat’s love affair with her character-come-alive marks a rupture with conventions and, potentially, with her husband and the regime. Yet, ambiguity persists. She feels that Arab national causes are dead, but sees no alternative other than immersing herself in love. Her affair awakens her senses and causes her to rethink many of her notions about human relations, but it also gives parts of her story a somewhat self-centred slant.

Hayat only spends time with her mother and sister-in-law, both women of traditional, limited outlooks on life. When she explains that she prefers the company of men, since women’s frivolity gets on her nerves, one wonders why she doesn’t seek out like-minded women friends — or why Mosteghanemi doesn’t give her any, so that she is not only reacting to the men in her life. Is the reader to understand that Hayat is the only relatively unconventional woman in Algeria?

The encounters between Hayat and her lover are few, but powerfully described. Mosteghanemi has made a fine art of conveying sensuous and psychological experience, sometimes erotically, but without ever descending into the pornographic. The coming together of the two lovers is not only a meeting of bodies but of minds — “a linguistic fencing match in which I found myself being defeated in round after round”, as Hayat says. (p. 210)

Their relationship reveals the significance of both language and silence, of what happens, as well as what might have happened, or may happen in the future — if there is one.

In the end, it is love and fate that dominate the novel, fulfilling Hayat’s wry words at the beginning about the illusions of “the novelist, who, mistakenly imagining that she owns the world by proxy, toys with the fates of creatures of ink before closing her notebook and becoming, for her part as well, a puppet suspended from invisible strings or moved, like others on life’s vast stage, by the hand of Fate”. (p. 23)

Mosteghanemi’s imagination is expansive; her prose is fluid, contemplative and poetic, peppered with numerous literary allusions, and well-served by Nancy Robert’s beautiful translation. It is hard to put this book down.

Related Articles

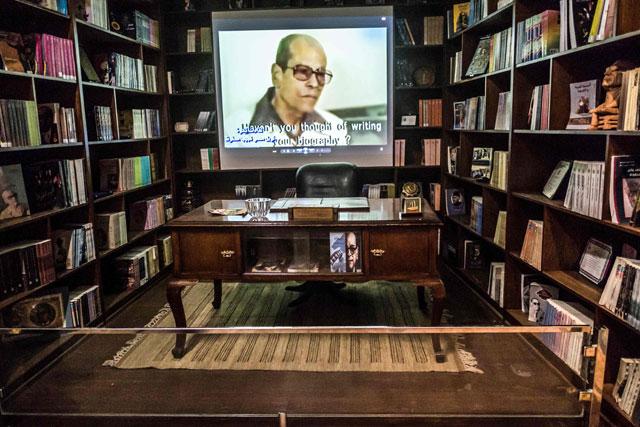

CAIRO — The legacy of Islamic Cairo's most famous son Naguib Mahfouz lives on in its winding lanes more than three decades after he became t

The Valley of AmazementAmy TanNew York: HarperCollins, 2013Pp.

The motto of Interlink Publishing is “changing the way people think about the world”. Choosing to republish “Sherazade” is clearly in line with this aspiration, for the novel gives fresh, first-hand insight into the chaotic, marginalised lives of young, second-generation immigrants in a big city like Paris.