You are here

Collusion across the Straits of Gibraltar

By Sally Bland - Apr 17,2016 - Last updated at Jan 28,2018

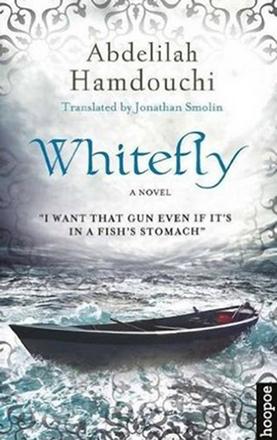

Whitefly

Abdelilah Hamdouchi

Translated by Jonathan Smolin

Cairo: Hoopoe/AUC Press, 2016

Pp. 136

Moroccan writer Abdelilah Hamdouchi is a pioneer of police fiction in Arabic, but he doesn’t limit himself to crimes and how they get solved. In the tradition of the Swedish partner-writers, Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo, many of his stories have social and political overtones. “Whitefly,” originally published in Arabic in 2000, is no exception.

Much is packed into this relatively short, fast-paced novel. Detective Laafrit’s efforts to unravel a puzzling crime take him from dilapidated police stations to fancy nightclubs and mansions, from the streets of Tangiers to isolated rural areas, from the sea to the mountains. Cooperation with the Spanish police leads across the Straits of Gibraltar to the miserable camps of immigrant farmworkers in Almeria, and plays no small part in unlocking the puzzle. With sparse, well-chosen words, Hamdouchi gives a taste of life in all these settings, and manages to make even secondary characters come alive, including a belly dancer, a reformed human trafficker and a couple of Sufi policemen.

Many aspects of modern-day Morocco are on display, including its place in the triangle of agricultural competition with Spain and Israel. This is not the Tangiers which inspired many American and European writers and artists in the past, but the Tangiers of modern globalisation. While the city retains a certain beauty, like Morocco itself, it is plagued by unemployment, poverty, drug smuggling, human trafficking and remnants of colonialism. As one policeman says, “Here’s Morocco today, a country without fish because Spanish fleets have cleaned out our seas. Thousands of their fishermen make their living off our shores while our children fatten their fish with their corpses.” (p. 22)

Meanwhile, a mysterious blight is destroying tomato crops — a main export and staple of local food.

Police detective Khalid Ibrahim, whose nickname, Laafrit, means crafty in Moroccan Arabic, is the hero of the story, but he is not Superman. He suffers from everyday ailments — the difficulties of quitting smoking, upset stomachs and problems with his wife. His reputation and nickname derive from his intellect and devotion to his job. As the only cop in Tangier who speaks Spanish fluently, he is designated to work with the Spanish police to fight drugs and illegal immigration. That is why he is called in when four bodies wash up on the shores of Tangiers. It is assumed they are “harraga” — illegal immigrants who throw away their IDs and crowd into pateras, hoping to cross the Mediterranean to Spain and get work, but sometimes drowning instead.

Still, the case is unusual because most immigrants no longer embark from Tangiers but from the Spanish enclaves, Ceuta (Sebta) and Melilla, vestiges of colonialism on Moroccan soil. This causes Laafrit to examine the bodies more closely, and he discovers that one of them was shot before being dumped into the sea, making the case even more unusual because of the use of a gun. Here one learns something interesting about Morocco: Unlike in many countries of the world, possessing a gun is highly exceptional. Even big drug smugglers don’t ordinarily have one, making one of Laafrit’s assumptions about the crime’s motive — a drug deal gone bad — questionable. Indeed, while drugs and human trafficking are involved, the network he discovers is much more complex.

The opening pages of the novel not only reveal the crime but are also infused with hints about the prevailing socioeconomic and human rights situation. As Laafrit heads for the commissioner’s office, he encounters demonstrations of unemployed youth and university graduates “raising long banners written years ago, still bearing the same slogans, all of them demanding work and criticising the government.” (p. 3)

With this small detail, Hamdouchi shows that the problem of unemployment is pervasive and persistent. The street is crowded with police and vans ready for anticipated arrests. It is assumed that the police will break up the demonstrations violently. Indeed, throughout the novel, it is clear that the police enjoy extensive powers. They have no need for warrants to search or arrest. On the other hand, their offices are shabby; they have no cafeteria and do not receive overtime pay. Still, a flashback into the youth of Laafrit and his wife, who met at Marxist student gatherings, shows that much has changed since the cruel persecution of the opposition at that time.

“Whitefly” is one of the first titles to be published by Hoopoe, a new division of The American University of Cairo Press, which bills itself as “an imprint for engaged, open-minded readers hungry for outstanding fiction that challenges headlines, re-imagines histories, and celebrates original storytelling”. Judging from “Whitefly”, this is a new source of exciting reading.

Related Articles

RABAT — Morocco on Monday arrested four suspects allegedly linked to the Daesh group who were plotting "dangerous and imminent terrorist" at

RABAT — Spanish pro-migrants activist Helena Maleno said on Monday that a Moroccan court has dropped human trafficking charges against her,

TANGIERS, Morocco — For scores of African migrants, it's a case of "Europe or bust", no matter what Moroccan authorities throw at them in th