You are here

An assembly line in the head

By Sally Bland - Jan 08,2017 - Last updated at Jan 08,2017

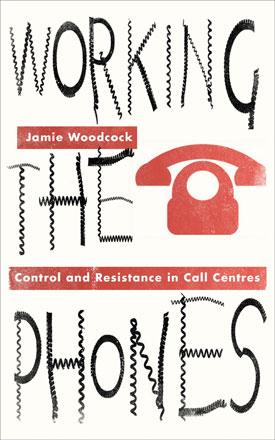

Working the Phones: Control and Resistance in Call Centres

Jamie Woodcock

London: Pluto Press, 2017

Pp. 200

In the tradition of investigative journalism and inquiry into workers’ conditions, Jamie Woodcock, a fellow at the London School of Economics, took a job at a UK call centre in order to find out how such workplaces operate from the inside. Focusing his research on employee-management relations, he compared what he observed to conditions at other work places as well as to classical Marxist theory about capital and the exploitation of the working class, and newer interpretations about the possibilities for workers’ control.

While one may associate call centres with India, or consider them a marginal part of today’s world economy, Woodcock presents facts and figures that prove otherwise: Starting in the mid-1990s, the most dynamic area of growth in white-collar employment internationally has been in call centres. One million people are estimated to work in call centres in the UK alone, leading some to dub them “the factories of our times”. Call centres are, moreover, emblematic of the shift towards a post-industrial service economy and the growth of neoliberalism which promotes deregulation, privatisation and cut-backs in state-provided social welfare. Thus, Woodcock has every reason to extrapolate from his experience at a particular call centre to draw conclusions about the situation of workers today around the globe.

Call centres did not just emerge because they were convenient for some businesses. Woodcock explains how they proliferated in the 1980s, based on capitalism’s drive to maximise profits and reduce costs in the context of the neoliberal economy. There are different kinds of call centres, but his research pertains to those where employees make unsolicited calls trying to sell products or services, in this case insurance.

The workforce and conditions at the call centre where Woodcock worked were typical. Most of the employees were young, female, considered unskilled and low paid. Working conditions were poor, and employment was precarious; there was no job security and no union; management techniques were rigid and sometimes abusive. There was also a high degree of stress with workers cajoled or threatened to meet targets for the number of calls and sales made. There was also the pressure of having to perform emotional labour to meet targets. Management required that employees sound happy and positive all the time in order to persuade customers to buy. In short, emotions are used to make money in sales call centres, increasing the employees’ alienation from their work.

Woodcock poignantly describes the high level of stress he observed among employees, and attributes it to the combination of technology, aggressive management techniques and emotional demands made on them. While viewing call centres as factories can be misleading in some ways, the work process does create a kind of assembly line in the heads of the workers. They no longer dial numbers themselves; rather, outgoing calls are automatically dialled and connected, while incoming calls are queued and distributed, vastly increasing the volume of calls to be handled and thus the pressure on workers.

Woodcock reminds that technology is never neutral and explains how the integration of computers and telephones makes for constant, detailed supervision and data collection. Digital recording means that every encounter with a customer is stored away, able to be recalled at any time. As a result, his fellow employees felt the power of management’s gaze constantly. The fear of a recorded conversation coming back to haunt a worker — or worse deny them of their monthly bonus — kept behaviour in check.

The ultimate aim of Woodcock’s research was to find out if workers resist in such conditions. Interviews with people working in other call centres revealed that there were occasional strikes, but most resistance was more low-key. At the call centre where he worked, he witnessed instances of refusal to work and cutting work time shorter without being discovered. The book also explores strategies for how call centres could be managed in a less stressful, more fulfilling way. For example, what would happen if workers controlled the call centre? Woodcock concludes that most would like to stop making unsolicited calls and so would simply turn off the system and leave. This highlights the fact that sales call centres produce little in the way of social value. “Working the Phones” is an invitation to ponder the meaningfulness of work or lack of same in our modern age.

Related Articles

The Mythology of Work: How Capitalism Persists Despite ItselfPeter FlemingLondon: Pluto Press, 2015Pp.

AMMAN — A labour report on vocational health and safety conditions for workers in the northern region’s municipalities indicated an increase

AMMAN – The dispute between Lafarge Cement Jordan and its employees ended on Monday evening after negotiations led by the Labour Ministry.&n