You are here

‘All mankind is my homeland’

Mar 26,2017 - Last updated at Mar 26,2017

Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders

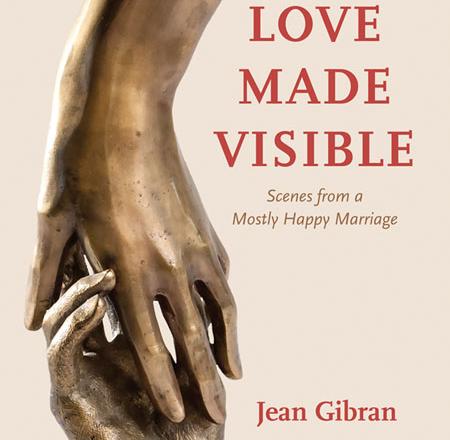

Jean Gibran & Kahlil G. Gibran

Massachusetts: Interlink Books, 2017

Pp. 524

This biography of the famous poet and artist is the result of decades of research by a husband-wife team: Gibran’s relative and namesake, Kahlil G. Gibran, and his wife, Jean. Not content with previously published sources or hearsay, they sought out his letters and the diaries of close friends. The result is a comprehensive picture of Gibran’s thinking, social being and work, of his family and Boston’s Syrian community, and of his cultural contemporaries in Boston and New York. In the authors’ words: “Probably the greatest problem in dealing with Gibran’s life was his duality. Constantly, the theme of divided loyalties to two languages, two careers, two often conflicting sets of associates, dominated his development, with the result that biographers and historians have been biased, aware of one perspective and neglectful of the other… We have attempted in our work to show Gibran’s several worlds, and the way he lived in them all”. (p. xv)

If (like this reviewer) one mainly knows Gibran as the author of “The Prophet”, one will not be surprised to read how ahead of his times he was. Think that a book published in 1923 was adopted as a spiritual guide by the 60s generation which ostensibly rejected all that went before! Truly, he was a forerunner of today’s cross-cultural bridging. On the other hand, one will be greatly enlightened by reading how versatile Gibran was in both his talents and social relations, how he developed in the visual arts and what influenced him from both sides of the Atlantic.

Emigrating from Lebanon at the age of eleven, and living with his family in south Boston’s squalid Syrian quarter, made Gibran an outsider, but his creative spark soon paved his way into bohemian cultural circles. While some of his first mentors were attracted by his “exotic” origins, later he was accepted by virtue of his artistic ability and vitality. He developed solid friendships and working relations with many American artists, writers, publishers and cultural personages, particular Mary Haskell, an educational reformer, for many years his patron and collaborator in writing. The authors’ extensive quotes from her copious diaries contribute greatly to understanding Gibran’s deeply humanist philosophy of life, and also the personal and artistic dilemmas he faced.

Though, potentially, he could have, Gibran never tried to “escape” his immigrant origins. “Instead of abandoning his origins, as so many first-generation immigrant children did, he began to understand that his background could further his artistic growth”. (p. 47)

Gibran was very close to his family, suffering greatly from the premature death of his mother, brother and sister, while remaining loyal to his remaining sister all his life, even after he moved to New York, and into quite cosmopolitan circles. He retained his emotional attachment to Lebanon and his home village, Bsharri, agonising over the famine caused by World War I, and passionately advocating Syrian independence. He was also deeply involved in Syrian-American social, political and literary affairs, contributing to the Arab immigrant press, and serving as president of the Pen League, the first Arabic literary organisation in the US, which pursued the same goals as the Nahda movement centred in Syria and Egypt.

Straddling different worlds and commitments was challenging and sometimes led to exhaustion and personal crises, but in the end it seems clear that it was Gibran’s ability to embrace and synthesise seeming opposites that made him a creative genius with a universal message. In his words, “For the earth in its all is my land… And all mankind my countrymen”. (p. 129)

Born into Christianity, Gibran synthesised its message of love with the positive values of Islam, especially Sufism, and other religions, arriving at a human-centred spirituality whereby people are in perpetual motion to discover their “greater self”, as he called it. This mixing of different religions, added to his critique of institutionalised religion, and the nudity in his drawings, scandalised many in his homeland and some in the US, but is actually the key to his great and lasting influence, as is most obvious in the enduring popularity of “The Prophet”. Ever self-critical, Gibran was something of a paradox. In one sense, he was an iconoclast, throwing out stagnant literary, social and religious conventions, but addressing the most basic and ancient of human questions about life.

“While honouring and asserting the beauty and richness of Arabic language and culture, Kahlil’s forward-looking perspective as an increasingly globalised citizen-artist rejected conditions of belonging defined or restricted by race or ethnicity, religious creed, gender, privilege, or circumstances of birth. Instead, individuals should be encouraged to unfold and exercise their talents as a community of citizens”. (p. 283)

His writings got to the heart of people’s relations to each other and to the universe, covering friendship and solitude, the meaning of parenthood, life and death, and other existential questions.

Working together with Alfred A. Knopf, who published his most seminal works, Gibran was ever concerned about the crafting of books, the illustrations and covers. The authors have honoured his concern, garnishing the text with an elegant cover and a large number of illustrations of his drawings, paintings and designs, as well as photos of his family and friends, making this a beautiful volume worthy of its subject.

Sally Bland

Related Articles

Despite the subtitle, this is more than a memoir of a marriage, for both Jean and Kahlil Gibran are/were such remarkable people, so deeply engaged in the arts and their community. Coming from a conservative New England family, Jean faced much opposition to her marrying a “foreigner” (who was US-born), but she took it all in stride.

Reviewed by Riad Al KhouriAMMAN — Recent events show Lebanon as dangerously unstable, but it was — and is still — also much more than that,

AMMAN — An artistic evening commemorating the memory of noted Jordanian novelist Mu’nis Razzaz was held in the Ousama Mashini Theatre for vi