You are here

‘I was gone’

By Sally Bland - Jul 26,2020 - Last updated at Jul 28,2020

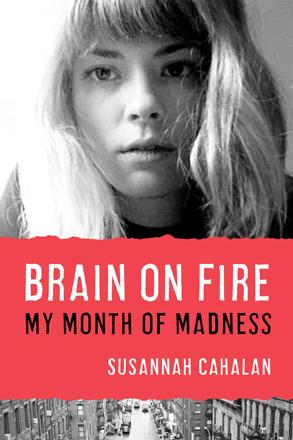

Brain on Fire: My month of madness

Susannah Cahalan

London: Penguin Books, 2014

Pp. 284

At first glance, one might think that the title of this memoir is rather sensationalist, but halfway through the book one learns that this is how Dr Souhel Najjar, a neurologist at New York University Hospital, described Susannah Cahalan’s illness to her and her parents. At that point, they had been desperately seeking a diagnosis for over two weeks; panic was setting in as Susannah’s very life was at risk.

Cahalan was a vivacious, promising, 24-year-old journalist at The New York Post, who began having odd visual, physical and emotional symptoms and exhibiting bizarre behaviour, culminating in a seizure that led to her hospitalisation. There, she totally lost her memory, strength and dexterity. She could hardly read, write, speak clearly or walk. Most devastating was that she felt she had lost her self: “I remember only very few bits and pieces, mostly hallucinatory, from the time in the hospital… the break between my consciousness and my physical body was now finally fully complete. In essence, I was gone.” (p. 72)

In “Brain on Fire”, she describes her experience of a month at the hospital and subsequent months of a slow, but fruitful recovery process. To reclaim the month when her memory was completely erased, she relied on interviewing her parents, boyfriend, medical personnel, friends who had visited her, and hospital video footage of herself. She also did extensive research on the rare disease she suffered from: NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis. Her memories and findings were first published in a long article in The New York Post when she was able to return to work, and then formed the basis for this book. Recording her memories, bolstered by medical information on the brain, how it functions and what can go wrong, was obviously part of her healing process. Yet, her book is equally a plea for more attention to autoimmune diseases that often go undiscovered and more empathy for those who have them; she dedicates it to “those without a diagnosis”. It is amazing that so soon after her recovery, she turned her attention to others. “If it took so long for one of the best hospitals in the world to get to this step, how many other people were going untreated, diagnosed with a mental illness or condemned to a life in a nursing home or a psychiatric ward?” (p. 151)

There is much to be learned from this memoir. Despite a highly competent medical team, getting a diagnosis was one, if not the most difficult part, as experts vacillated between mononucleosis, epilepsy, various forms of psychosis and other ailments. Enter Dr Najjar who gave her a simple pencil-and-paper task: to draw a clock and place the numbers on it, which enabled him to locate the source of her problem in the right hemisphere of her brain. Without underestimating the importance of technology, this shows we should not neglect simple, tried-and-true methods.

The other crucial element in Najjar’s approach was that he reawakened Susannah’s nearly deleted sense of self and self-confidence. As she writes, “Then he did something none of the other doctors had done: Najjar redirected his attention and spoke directly to me, as if I was his friend instead of his patient… He had an intense sympathy for the weak and powerless, which, as he told me later, came from his own experience as a little boy growing up in Damascus,” when his intellectual abilities had been severely underestimated by his parents and teachers alike, until a perceptive teacher took a special interest in him. “His own story carried with it a moral that applied to all of his patients: he was determined never to give up on any of them.” (pp. 128-9)

Until then, only Susannah’s parents and boyfriend had shown that kind of personal devotion, spending unlimited time with her and constantly looking for her old self beyond the disconcerting symptoms she displayed. Their support looms large in the factors that facilitated her recovery. The fact that she was seamlessly welcomed back to her job at The New York Post was also important.

The overarching lesson in Susannah’s story is the need for breaking down the barriers between psychology and neurology, “urging for one uniform look at mental illnesses as the neurochemical diseases that they are… Dr Najjar, for one, is taking the link between autoimmune diseases and mental illness one step further: through his cutting-edge research, he posits that some forms of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression are actually caused by inflammatory conditions in the brain”. (p. 225)

Connections are also being found between autism and autoimmune disorders, and with recent reports of the cognitive after-effects of COVID-19 on some patients, the issues raised in this book have added relevancy.

As one might expect from someone in her profession, Cahalan’s writing is impeccable. She skilfully intertwines valuable scientific information with her own perceptions and feelings. She also asks the relevant questions, approaching her own case with the sharp tools of investigative journalism. The same sparkling personality and love of life that she was able to rediscover in herself, make her book especially compelling.

This is a must-read for anyone concerned with mental health. “Brain on Fire” is available at Legenda Bookstore.

Related Articles

10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange WorldElif ShafakLondon: Viking/Penguin Random House: 2019Pp.

In boys with and without Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, new research has found that an extra daily dose of Omega-3 fatty acids reduced symptoms of inattention.