Human Rights Watch (HRW) this week issued a 79-page report providing detailed evidence of indiscriminate violence perpetrated by armed opposition groups against civilians in Syria since the conflict there began in 2011.

The report states that armed groups attack civilians in government-held territory with car bombs, rockets and mortars that killed and maimed thousands, in contravention of the laws of war.

The report, titled “He didn’t have to die: Indiscriminate attacks by Syrian armed opposition groups”, documents scores of such attacks in heavily populated areas in Damascus and Homs between January 2012 and April 2014 — attacks which continue until today.

The findings are, says, HRW, “based primarily on victim and witness accounts, on-site investigations, publicly available videos and information of social media sites”.

The HRW regional deputy chief, Nadim Houry, stated: “We’ve seen a race to the bottom in Syria with rebel groups mimicking the ruthlessness of government forces with devastating consequences for civilians.”

Houry’s admission is belated. These equally ruthless groups have been punishing civilians from the onset of the unrest.

The report describes actions carried out by the Western-backed Free Syrian Army, the Islamic Front, Jabhat Al Nusra, Daesh and other groups.

HRW also found that neighbourhoods inhabited by minorities were more frequently and expressly targeted because the largely Sunni armed groups perceived them to be supporters of the government.

Such attacks were also carried out in retaliation for strikes by government forces on opposition-held areas.

In spite of its faults, it was about time such a report was issued by HRW.

Armed opposition groups have escaped international condemnation for too long. Indeed, it is only since Daesh swept into Mosul in Iraq that HRW and other entities have been taking notice of how these factions have been behaving in Syria.

While HRW and others have repeatedly documented government attacks on populated areas of cities and towns captured and held by opposition factions, in such reports they did not point out that the armed groups — initially regarded as “rebels”, now seen as “terrorists” by many in the international community — were holding civilian populations hostage and using them as human shields.

Social media and Internet video material exposing the horrors of heavy bombing or rocketing by government forces have been used as propaganda by the opposition and its allies as if the armed groups were not to blame for the attacks in the first place.

If they had not taken over certain areas, there would have been no attacks, indiscriminate or targeted.

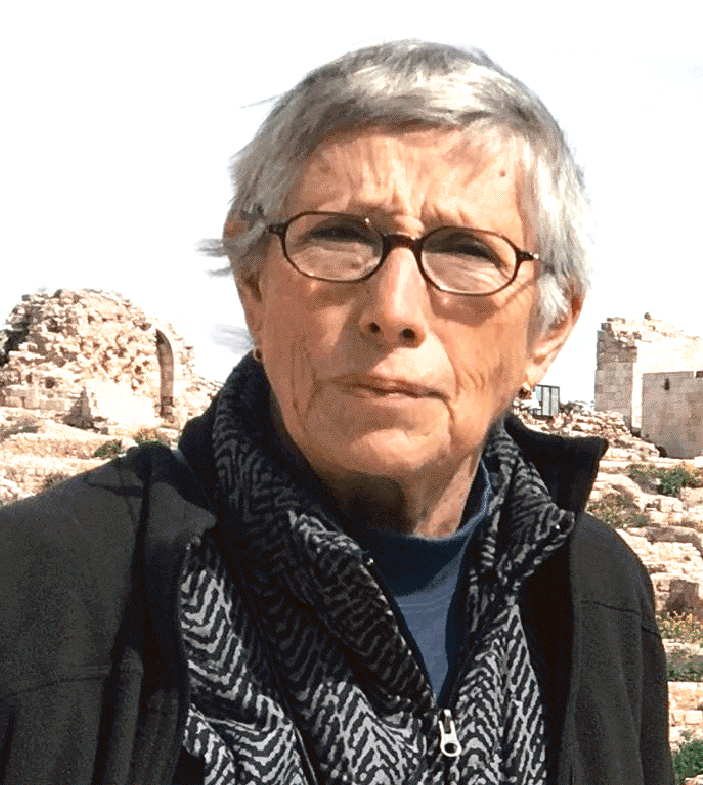

I have spent more time in Syria since the conflict began in 2011 than during the previous decades I lived in this region.

During my visits — which began in November 2011 — I met many people and discussed what has been happening to this central Arab country.

While many castigated the government for using force against demonstrators in Deraa and elsewhere during the early months of 2011, they also said that protesters, perhaps infiltrated by agents of the Muslim Brotherhood or other dissident groups, also used violence, burning down Baath Party offices, attacking banks and robbing ATMs.

Furthermore, the unrest was fuelled by foreign intervention.

The so-called Free Syrian Army (FSA) was formed and fostered by Turkey in July 2011. This amounted to a flagrant violation of Syria’s sovereignty by a neighbouring power.

Turkey later sponsored the creation of the expatriate political opposition Syrian National Council (SNC), which morphed, under Qatari patronage, into the Syrian National Coalition.

The FSA has always fronted for a diverse collection of armed groups. Today, the majority is fundamentalist, while the SNC — now the Syrian National Coalition — is an equally disparate body that has no followers in Syria and no influence on the actions of the FSA.

During my visit to Damascus this month, a veteran foreign observer of the Syrian scene dubbed the FSA a “logo”. This characterisation could very well fit the SNC as well.

One of the most impressive of my interlocutors was a barber called Ahmad from the western Damascus suburb of Muadamiya. I have written about Ahmad because he is a wise man who understood the deadly and destructive games being played in Syria from the beginning.

I met him early in 2012 in his comfortable, middle-class home down a narrow side street in this majority working-class quarter, a ten-minute drive from the upscale diplomatic quarter of Damascus.

He said at that time that expatriate Syrian businessmen were providing teenage boys and young men with guns transported from Lebanon into Syria along traditional routes used to smuggle foreign brand cigarettes or other goods. Most of the weapons were old, some leftovers from the Lebanese civil war (1975-90).

Ahmad said the youths were largely recruited by local gang bosses and thugs with the aim of extorting money and thieving from their own communities.

They also attacked police posts and fired on army patrols and checkpoints, attracting return fire and hot pursuit from the security forces, and when the situation became intolerable, shelling and air strikes from the army.

When this happened, the government was condemned for using force against civilians.

Others confirmed this scenario and pointed out that no government determined to maintain order accepts that armed factions take over neighbourhoods, cities or towns in order to mount an insurrection.

As far as Syria is concerned, my old friend, the late Patrick Seale observed: “One must not forget that the government plays by Hama rules,” referring to the crushing of armed Muslim Brotherhood elements that took over the old city of Hama in 1982, following several years of violent attacks.

It is difficult to say what would have happened in Syria if, as some claim without taking into consideration the facts, the protests had been peaceful, the guns did not appear, and the government refrained from or stopped cracking down with lethal force.

The original protests called for reform, an end to corruption, and democracy, and not regime change.

Although the youngsters arrested and beaten in Deraa had written on the walls the slogan of the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings, “Ash shaab yurid isqat al nizam” (“The people want to bring down regime”), they were almost certainly imitating demonstrators in Cairo’s Tahrir Square where, during 18 days of constant protest, there was no damage to shops, restaurants or banks.

This slogan was not adopted by Syrian protesters until after the crackdown, which could have been finessed by both sides. This did not happen — tragically for Syria.