You are here

Historians recall reasons behind construction of Hejaz Railway

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Sep 25,2022 - Last updated at Sep 26,2022

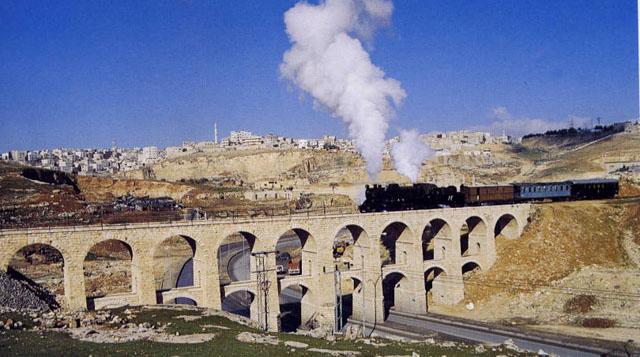

A view of the Hejaz Railway station in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia (Photo courtesy of ACOR/Jane Taylor Collection)

AMMAN — The Hejaz Railway was “a monumental feat of engineering and a triumph of Islamic financing over Western capital, and the last desperate act of modernity of a failing empire”, according to a British researcher.

“This railway enhanced the status of the Ottoman Sultan as Caliph to the world’s Muslims and threatened British interests in the Middle East and India. It was built primarily as a holy or pious railway to transport Hajj pilgrims to Mecca,” said John Winterburn from Oxford University in a recent e-mail interview with The Jordan Times.

It was a single track, narrow-gauge (1.05 m), railway extending 1,302km from Damascus to Medina, Winterburn continued, noting that the construction began in 1900 and was completed in 1908.

“The railway reduced a typical 40-day journey by camel caravan to just four days,” Winterburn said, adding that there were also connections in Damascus to the railway to Haifa and Aleppo.

There were multiple reasons behind the construction of the Hejaz Railway: Religious, political, strategic and economical, said James Nicholson, the author of the book “The Hejaz Railway”.

“By matching the European industrial achievement with a railway project on a massive scale, Abdulhamid II could bolster his claim to be recognised as the leader of the Muslim world,” Nicholson said.

He added that from the economic standpoint, the project would stimulate trade, agriculture and urban development, as well as allow taxation to be extended into some of the more remote areas of the empire.

The Hejaz Mountains were the biggest obstacle according to Winterburn, adding that in November 1920 Prince Abdullah travelled by train to Maan from Medina and established the National Defence Centre in the house that had been built for German engineer Heinrich August Meissner (1862-1940) at Maan Station and which later became the first Royal Palace in Jordan.

“In June 1946, the 2nd Yarmouk Bridge on the Haifa-Deraa branch was demolished by Jewish saboteurs. Services between Palestine, Transjordan and Syria were cut, and when an attempt to rebuild the damaged bridge was abandoned, the Hejaz Railway lost its Mediterranean port outlet,” Nicholson said.

In the later decades, the railway lost its importance and other means of transport replaced the train.

“The construction of another short spur-line, in 1975, from the main line to the opencast phosphate mines at Al Hasa and a new line from Batn Al Ghoul, 54km southeast of Maan, to Aqaba was built to facilitate the development of Jordan’s phosphate reserves. Further north, a section from Menzil to Al Hasa was also upgraded,” Winterburn said.

“Speaking for myself, I think it would be a great shame if a modern line was built over the original one, as this would obliterate a splendid historic monument. With so much empty space available [particularly in the long Saudi Arabian section] on either side of the line, it would certainly be preferable if any new track was built alongside the original one, thus preserving the wonderful old stations and bridges of the Hejaz Railway,” Nicholson said.

Related Articles

AMMAN — While southern Jordan witnesses an abundance of ancient sites, a British archaeologist decided to study the 20th century archaeology

AMMAN — British colonial architecture in Jordan was the focal point of a workshop held at the Council for British Research in the Levant (CB

Thousands of Jordanian Muslims returned this week from Mecca after undertaking the greater pilgrimage known as Hajj.