You are here

Long despised, tattoos emerge from shadows in Tunisia

By AFP - Dec 20,2018 - Last updated at Dec 20,2018

TUNIS — Once widespread in rural Tunisia, tattoos have long been considered vulgar and associated with convicts or the uneducated.

But now they are emerging from the shadows as young people like Ghada Atiaoui get inked and take up courses at the first tattoo school in the Arab world.

The 19-year-old, who also studies tourism and hospitality, says she was drawn to the training by a "passion" for tattooing, but not only that.

"It's an art and a profession of the future and it's a field where there aren't many women, which is a challenge for me," says Atiaoui.

Leaning over a piece of synthetic skin, she sketches out sophisticated geometric figures in Chinese ink before switching to a tattoo machine.

In her class, the eight other students, aged 19 to 31, also hope to graduate as professional tattoo artists. Currently, most tattooists in Tunisia work illegally without authorisation from the authorities, in a profession that has only emerged as such relatively recently.

"I'm enjoying myself with something I love," says Sami Essid, his arms proudly adorned with green motifs.

The 31-year-old physiotherapist hopes to open a tattoo service inside his clinic.

From passion

to profession

The state-sanctioned tattoo school opened last month in the chic Tunis neighbourhood of La Marsa, the first of its kind in North Africa and the Arab world.

It was founded by Fawez Zahmoul, a renowned tattoo artist who fought for the authorisation and acceptance of the profession and also helped to establish a workers' union.

The former engineer entered the field in 2006, going abroad to learn "a passion that has become a profession", he says.

Zahmoul, who also runs a tattoo parlour that was the first to be legalised in Tunisia, in 2016, says his goal is to share his knowhow.

It was a path that often saw him run into trouble, including being assaulted in the same year by four people who accused him of Freemasonry and selling Satanic services.

But "tattooing is no longer a problem as in the past in Tunisia, with the evolution of media in the world and the frequent sighting of tattooed stars and celebrities".

'New door'

Each Saturday and Sunday, for six months, his students are given lessons on hygiene and skills of the trade at a cost of 4,000 dinars ($1,360 or 1,200 euros).

One of the teachers, Amine Labidi, says the school has opened a "new door" for tattoo enthusiasts in North Africa and the Arab world.

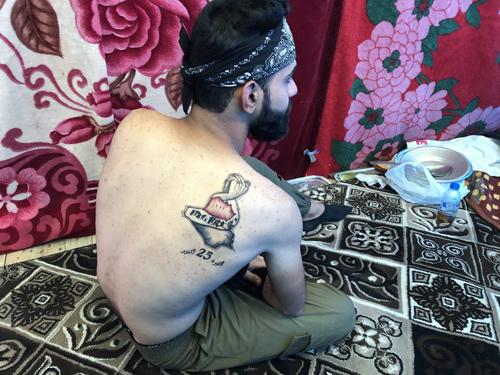

"In our day, we had a lot of trouble learning techniques and tips. I hope these new artists won't face the same difficulties," says Labidi, his body decorated with 40 tattoos including a flag of Tunisia.

"Arabs in general have not contributed much to the art of tattooing. We hope to add our contribution, with this school and with the generations we are training," says the 32-year-old.

For sociologist Abdessatar Sahbani, the growing popularity of tattoos in Tunisia reflects changes in society.

"A new type of tattoo is gaining ground today, influenced by Western techniques and trends," he says.

This is also the result of a "crisis of values" and the domination that politicians have over public space which pushes segments of society to resort to "more daring" means of expression, he added.

Tunisia is also home to a form of tattooing known as "El-wcham" which is practiced by secular Berbers for aesthetic reasons.

The symbols are etched onto the faces and bodies of Berbers using a blunt tool called the "mchelta".

But religious leaders condemned it, and city folk regarded these traditional devices as backward, especially when the country embarked on modernisation after independence in 1956.

Tattooing also suffered from being associated with crime and prisons, where, in the 1970s, inmates often marked names on their bodies.

"Morals change. In a few years, it will no longer be perceived as something bad or stigmatising," says Atiaoui.

But getting tattoos is still "something we do to rebel", her teacher Labidi chips in.

"It has never been an accepted art, never, neither in the past nor in the present, nor in Tunisia nor elsewhere."

Related Articles

TUNIS — Militiamen have kidnapped a group of Tunisian workers near the Libyan capital and are demanding the release of a comrade held i

BAGHDAD — At 16, Maram is as old as the political system she and fellow Iraqi youth are railing against.

TUNIS — A Tunisian commission tasked with securing justice for victims of decades of dictatorship called on Friday at its final congres