You are here

‘Holding the sun in our hands’

By Sally Bland - Nov 04,2018 - Last updated at Nov 04,2018

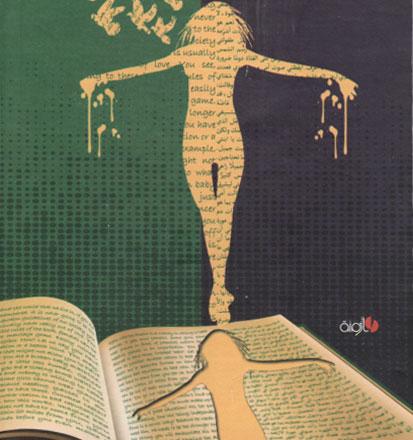

Bad Girls of the Arab World

Edited by Nadia Yaqub and Rula Quawas

Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017

Pp. 239

The word “bad” in the title of this book attracts attention and demands explanation. Co-editor Rula Quawas offers the following definition, showing that bad is used ironically: “The woman who dares to trample societal boundaries she had no part in creating in order to reclaim the power of her mind is likely to be labelled a ‘bad girl,’ improper and transgressive… Those who express themselves, refusing to be silenced, clear the way to equality and justice for others.” (p. 32)

Put in another way by Miral Al Tahawy: “’Bad girls’ do not peer fearfully around themselves, nor do they give great importance to their images in the mirrors of others; they do not consider red lines too seriously because they are more tolerant of their own faults and trained in toughness”. (p. 216)

As the other co-editor, Nadia Yaqub, points out, “women may choose to transgress social norms, or transgression may be thrust upon them”. (p. 3)

Alongside the daring women who purposefully brave the boundaries, are the “reluctant bad girls”, such as female orphans who are negatively labelled because of being born to an unwed mother with the father shirking paternal responsibility, leaving them without a legal status or family name. Another example of “reluctant bad girls” are the Palestinian mothers who were falsely accused of sending their children to die during the Second Intifada.

Fortunately, Rula Quawas saw this book through to completion but she never actually held the finished product in her hands. Reading her chapter “Inciting Critique in the Feminist Classroom”, one realises just how much women in Jordan and elsewhere lost with her untimely death, but also how much knowledge and inspiration she imparted in her all-too-short life. As she describes her teaching, “Through the critical thinking of a feminist theory class, some Jordanian students gradually learn to empower themselves and recognise their innate capacity for self-reflection, self-determination, and consciously guided action. By rebelling against conventional, deep-seated assumptions and value judgements, they acquire a new and better understanding of women’s reputations and how society conceptualises female goodness and badness.” (p. 28)

This can be a joyful process which Quawas expressed in a poem:

“Here we will stay. Jordanian women, uncovering the veils of ignorance.

Removing them from our souls, emerging as a fountain of hope, and holding the sun in our hands…” (p. 35)

Other chapters explore the experience of returning to an Arab country to teach after studying abroad, the difficulties of reconciling feminism with nationalism, the interplay between being female and other identities a woman may carry, and the conflicted relations between Arab and some Western feminists. Thinking out-of-the-box is typical for all the chapters in this book, but one in particular stands out for upending some common assumptions by addressing the conflicting narratives that arose in the wake of the Arab uprisings. While some lauded women’s strong, overt participation, others contended that this had not empowered them. While seeing truth in both these narratives, Amal Amireh contends that things are “less likely to change if revolutionaries insist that gender and sexuality are not central to the revolutionary process”. (p. 113)

To show that questions of gender and the body were intrinsic to the uprisings, Amireh examines the cases of four women who became famous during these events, including Fayda Hamdi who allegedly delivered the slap that drove Muhammad Al Bu’azizi to suicide and thus ignited the Tunisian revolution and showed the way for others. Her careful analysis reveals that gender did play a major role but in a much more nuanced and complicated way than usually assumed.

Two different chapters address outstanding writers, Samar Yazbek of Syria and Suhair Al Tal of Jordan, who broke with the traditions in which they were raised to write and act according to their convictions. Another chapter covers “Reel Bad Maghrebi Women”, filmmakers who depict “a new type of female protagonist who redefines the terms of her own oppression and possible emancipation”. (p. 167)

There is also a chapter on women singers in the Sudanese diaspora, whereby “alternative visions of Sudanese identity have emerged, and creative new artists have flourished beyond the reach of the state”. (p. 189)

The chapters in this book are varied in style, including personal experience, academic analysis and artistic contributions; they cover different Arab countries as well as Arab women abroad, different time periods and contexts, but they all converge on disputing, directly or implicitly, Orientalist notions that the oppression of Arab women is rooted in beliefs fundamental to Islam and Arab society. “Such culturalist analyses ignore how patriarchy as practiced in the Arab world today has grown out of colonial and neocolonial encounters with the West and the particular forms of modernity that have resulted from those encounters.” (p. 13)

Yet, in the afterword, writer Laila Al Atrash looks back at years of Arab women’s struggle for liberation, and queries: “I wonder how it is that we are still leading, decades later, the same fight against this attack on women and their accomplishments. How has our role, past, present and future, been eroded in the onslaught of politicised religion?” (p. 212)

Related Articles

Inkshedding Gender Politics: Academic Activism in Feminist TheoryRula Quawas, editorAmman: Azminah, 2017Pp.

AMMAN — “Build your own power bridge; say no to silence and always speak the truth,” was one line out of her tens of thousands aimed at impr

AMMAN — Stereotypes about the roles of women in society hinder their economic and political participation, experts said, calling for an educ