You are here

In Mosul, a long-term battle to repair Iraq’s heritage

By AFP - Feb 26,2017 - Last updated at Feb 26,2017

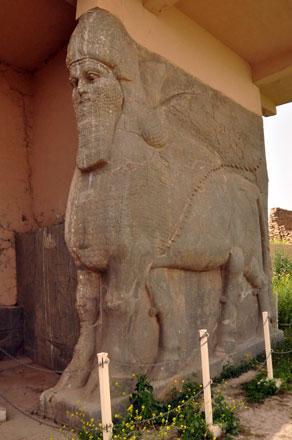

This file photo taken on April 9, 2013, shows an ancient statue of a winged bull with a human face, an indication of strength in the Assyrian civilisation, at the archaeological site of Nimrud that lies on the Tigris River, around 30 kilometres southeast of Mosul, Iraq’s second city (AFP photo)

PARIS — The city of Mosul is intertwined with human history, tracing its roots to 4,400 years ago when civilisation rose in fabled, fertile Mesopotamia.

Today, as Iraqi forces backed by an international coalition inch forward in their fight to recover Mosul from the Daesh terror group, historians are looking at how to save, repair or retrieve precious heritage after the extremists’ three-year reign.

At a meeting in Paris last week, Iraqi officials and dozens of experts from around the world agreed to coordinate efforts to restore Iraq’s cultural treasure.

But, they admitted, the road ahead will be hard and long.

“The main challenge is for Iraqis to deal with this task by themselves. It is important to empower the people,” said Stefan Simon, director of global cultural heritage initiatives at Yale university.

“It is a heart-breaking situation,” he added. “[...] Rehabilitation will take a very long time. They need patience. “

In 2014, at the zenith of Daesh’s self-declared “caliphate” in Syria and Iraq, more than 4,000 Iraqi archaeological sites were under the heel of the Sunni fanatics.

In the Mosul region alone in northern Iraq, “at least 66 sites were destroyed, some were turned into parking lots, Muslim and Christian places of worship suffered massive destruction and thousands of manuscripts disappeared,” Iraq’s deputy minister for culture, Qais Rashid, said at the conference, hosted by Unesco.

The most grievous blow has been suffered by the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud, believed to be named after the biblical hunter Nimrod.

Eighty per cent of the site has been destroyed, by extremists driving bulldozers and detonating explosives.

Nineveh, once the largest city in the world, has been 70-per cent destroyed.

‘Idolatry’

As for Mosul itself, historians are quailing at the likely fate of the city’s museum, the second largest in Iraq and a treasure house of ancient artefacts.

After suffering looting during the 2003 Iraq War, the museum was on the point of reopening in 2014 when Daesh took over.

The extremists immediately set about destroying objects from the Assyrian and Greek period, which they claimed promoted “idolatry”.

Grim discoveries by the Iraqi army in its advance towards the extremists’ bastion of west Mosul have prompted some specialists to fear the worst.

In mid-January, Iraqi troops in Neneveh liberated the reputed tomb of the Prophet Yunus — known to Jews and Christians as the Prophet Jonah.

“[It is] far more damaged than we expected,” Culture Minister Salim Khalaf said.

The site could collapse, because the extremists dug tunnels underneath, both to hide from attack and to dig for artefacts, he explained.

More than 700 items have been looted from the site to be sale on the black market, he estimated.

Iraq is turning to Interpol and other world agencies to track down the lost treasures. Under UN Security Council resolution 2199, all trade in cultural artefacts from Iraq and Syria is illegal.

“Daesh tried but will never erase our culture, identity, diversity, history and the pillars of civilisation,” Iraqi Education Minister Mohammad Iqbal Omar said.

France Desmarais, of the International Council of Museums, a professional museum group, said there was a long and tragic history of trafficking in cultural objects from northern Iraq.

However, “successive wars in Iraq since 2003 have created additional opportunities for the trade”, Desmarais said.

Universal values

The long-term needs of preserving Iraq’s ancient history are many. They start with securing and monitoring sites, drawing up an inventory of items that are safe or missing, restoring and digitising manuscripts — a task that is dozens of years in the making, and with a bill to match.

But culture embodies universal values, and there is a deep well of goodwill for this venture.

“Culture implies more than just monuments and stones — culture defines who we are,” says Unesco chief Irina Bokova.

That’s a point of view shared by Najeeb Michaeel, an Iraqi Dominican monk who saved hundreds of manuscripts from the 13th to 18th century, spiriting them to safety in Kurdistan just before Daesh began its destructive grip on the plain of Nineveh.

“We have to save both man and culture,” Michaeel said. “You cannot save the tree without saving its roots.”

Related Articles

Islamic State jihadists occupying parts of Iraq are destroying age-old heritage sites and looting others to sell valued artefacts on the black market, experts gathered at UNESCO's Paris headquarters warned Monday.

BAGHDAD — The Assyrian city of Nimrud, located in an area Iraqi forces said was recaptured during the operation to retake extremist-held Mos

MOSUL, Iraq — Iraqi officials on Thursday said Mosul’s once-celebrated museum had entered the final stages of restorations ahead of a planne