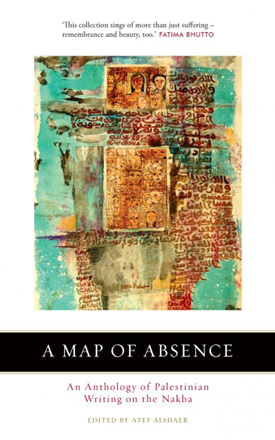

A Map of Absence: An Anthology of Palestinian Writing on the Nakba

Edited by Atef AlShaer

London: Saqi Books

Pp. 252

In “A Map of Absence”, forty-eight Palestinian writers and one Lebanese (Elias Khoury) recreate and reflect on the Nakba in poetry and prose. Most of the contributors are well-known; roughly one-third of them are no longer with us, but there are also new voices.

Despite their approaching the subject from different angles, certain themes stand out, from the trauma, disruption and deep, lasting sadness caused by the violent dispossession of 1947-48 and its aftermath, to Palestinians’ determination to remain connected to their land and culture.

The contents--poems, short stories, excerpts from longer fiction and memoirs, are arranged in chronological order from the 1930s until today. Introducing the book, editor Atef Alshaer divides these almost ninety years into three phases: The first is the immediate experience of the Nakba; the second, the formation of the Palestinian national movement and organised resistance, with Ghassan Kanafani bridging between these two phases. Nationalism was at the core of the first two generations’ vision, although many in the second generation in particular began to critique patriarchy and dictatorship.

However, as Alshaer points out, “The third generation of writers, writing after the Oslo Accords in 1993, are prepared to challenge elitism as well as questions of national identity.” (p. xvii)

While the early poetry, such as that of Ibrahim Tuqan, paints the national cause in sweeping terms, later poets began to employ more subtle techniques, evoking details of everyday life or encounters that speak to Palestinian memory and the ongoing effects of dispossession. A prime example is the poetry of Lisa Suhair Majaj who writes: “Fifty years on I am trying to tell the story of what we are still losing… in despair we seek the particular light angling gently in single rays.” (pp. 182, 184)

Mahmoud Darwish is of course a master in turning “small things” in nature or human encounters into potent symbols of Palestinian memory or identity, sometimes with universal implications. The title of this book partially echoes one of his metaphors: “Here the train fell off the map in the middle of the coastal path. And the fires flamed in the heart of the map, then winter extinguished the fires, though winter was late.” (p. 48)

In an excerpt from “Hunters in a Narrow Street”, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra poignantly relates how he lost not only his Jerusalem home but his young love in 1948; he also expands the humanistic scope of the Palestinian resistance by terming it “our ill-equipped defiance of hate”. (p. 27)

Such defiance seems particularly relevant today with the excessive displays of hate emanating from the extreme, right-wing, Israeli regime, though it should be noted that the Palestinians are now better equipped to combat this.

Palestinians have often employed irony to express the illogic of their dispossession, most famously in Emile Habibi’s “Pessoptimist” which satirises the situation of Palestinians remaining in Israel. Irony is also overwhelming when Edward Said discovers that his family home in Jerusalem has been occupied by the “International Christian Embassy”, a right-wing, Zionist-linked entity. He also notes the spiralling regional by-products of Israel’s colonisation of Palestine: “a vast militarisation took over every society, almost without exception, as it did also take over Israel”. (p. 39)

Adania Shibli’s acute sense of injustice is apparent in her commentary on Samira Azzam’s short story, “Man and His Alarm Clock”, which is also included in this anthology. It was the only Palestinian text allowed to be taught in schools by the Israeli Censorship Bureau, yet Shibli discovered its subtle subversion, which “contributed towards shaping my consciousness regarding the question of Palestine as no other text I have ever read in my life has done.

Were there one day Palestinian employees who commuted to work by train?... Was there one day a normal life in Palestine?… The text engraved on my soul a deep sense of yearning for all that was… normal and banal, to a degree that I could no longer accept the marginalised, minor life to which we’ve been exiled since 1948, during which our existence turned into a ‘problem’.” (p. 192)

Core questions are addressed throughout: injustice, memory, resistance, longing for peace and a normal life, and especially return to the homeland. Some address these questions very directly such as Dareen Tatour who was imprisoned for her poetry. Abdelkarim Al Karmi of the first generation entitles his poem “We Will Return”, while Tawfiq Ziad insists “We Will Remain”.

Writing today, Amira Sakalla, one of the new voices introduced in this book, proclaims “We weren’t supposed to survive but we did… We weren’t supposed to return but WE ARE” — significantly, this is the last line in the book that looks towards the future.” (p. 230)

Every selection in this book deserves comment, which is unfortunately impossible in a short review. “A Map of Absence” has the makings of becoming a classic, due both to its documentation of a seminal event and the beauty and intensity of the writing. In the words of editor Atef Alshaer, “Nowhere has the voice of Palestine resonated more powerfully than in the literature of Palestinians”. (p. xix)