You are here

Does progress bring happiness?

By Sally Bland - Jan 31,2021 - Last updated at Jan 31,2021

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

Yuval Noah Harari

New York: Harper Perennial, 2018

Pp. 443

Most history books are very specific, focusing on narrowly defined topics, locations or time periods. Yuval Noah Harari, a history professor at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, does the opposite, taking on the whole span of human existence and examining its physical, cognitive, economic sociological, cultural, and environmental dynamics.

Even more boldly, he demolishes major presuppositions and myths which most humans take for granted and regard as truths. To him, truth is to be found in science and even that is ever-changing in the light of ongoing research and discoveries.

“Sapiens” is nothing if not provocative. Many will be surprised, and some offended, that the first chapter of the book, which is about the evolution of early humans, is entitled “An Animal of No Significance” — could that be us? According to the author, “Animals much like modern humans first appeared about 2.5 million years ago. But for countless generations they did not stand out from the myriad other organisms that populated the planet.” (p. 4)

Harari discusses what features, such as extraordinarily large brains, distinguish humans from other animals, as well as the drawbacks of overly large brains and theories of how Homo sapiens became the dominant type of human. Another distinguishing feature is that “since humans are born underdeveloped, they can be educated and socialised to a far greater extent than any other animal”, a fact that has had an enormous impact on subsequent history. (p. 10)

The book is divided into four parts: The Cognitive Revolution, the Agricultural Revolution, the Unification of Mankind, and the Scientific Revolution. While the general outline may be familiar to an educated reader, Harari’s gift is bringing out the ironies and real drama of history, explaining what various changes meant for humans’ everyday lives and for the future. To do so, he links seemingly unrelated phenomena, recasts ancient events in modern-day metaphor, and poses questions of current relevance.

The evolution of their language is key to Homo sapiens’ success: “As far as we know, only Sapiens can talk about entire kinds of entities that they have never seen, touched or smelled” which enables extensive social cooperation and collective imagination, including human trust in intangibles such as the value of money and joint-stock companies: “That’s why Sapiens rule the world, whereas ants eat our leftovers and chimps are locked up in zoos and research laboratories.” (pp. 24-5)

There are many shockers in this book, such as when Harari sums up the Agricultural Revolution as “History’s Biggest Fraud”. However, he argues persuasively for this as well as for his other contentions: “The Agricultural Revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into a better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites… Everywhere, rulers and elites sprang up, living off the peasants’ surplus food and leaving them with only a bare subsistence.”

(p. 101)

Similarly, a survey of political systems from the time of the Hammurabi Code to American democracy, which coexisted with slavery and racial segregation, confirms his view that there is no justice in history: “Most sociopolitical hierarchies lack a logical or biological basis — they are nothing but the perpetuation of chance events supported by myths.” (p. 144)

Part 3 traces the emergence of universal orders — money, empire, and religion, from the first millennium BC on. Then, about 500 years ago, the Scientific Revolution erupted, ironically by humans admitting their ignorance and their need to know. This motivated the European imperialist voyages of “discovery”, seeking new knowledge and new territory and wealth to conquer. “Science, industry and military technology intertwined only with the advent of the capitalist system and the Industrial Revolution. Once this relationship was established, however, it quickly transformed the world.” (p. 264)

The predominance of capitalism also changed ethics: Its rise was coupled with the destruction of indigenous cultures and the advent of the Atlantic slave trade, as the profit motive became all pervasive with no guarantee of just distribution. While millions died due to colonial and religious wars and Nazism, “Capitalism has killed millions out of cold indifference coupled with greed.” (p. 331)

Two additional themes run throughout the narrative: the enormous cruelty inflicted on domesticated animals as a result of industrialised agriculture, and the huge changes that human endeavour has caused to the environment. (Harari deliberately does not call it the destruction of nature, as he contends that nature cannot be destroyed.) Still, he concludes, “all of these upheavals are dwarfed by the most momentous social revolution that ever befell humankind: the collapse of the family and the local community and their replacement by the state and the market”. (p. 355)

After treating the reader to this sometimes-harrowing review of history, Harari asks if humans are happier in view of the way things have developed. Proceeding to assess the pluses and minuses, his answer is equivocal. Not knowing how human achievements have influenced the happiness and suffering of individuals is, according to him, “the biggest lacuna in our understanding of history. We had better start filling it”. (p. 396)

The book’s last chapter is literally mind-blowing as Harari sketches the possible consequences of current technological research whereby scientists are engineering living beings in laboratories, replacing the laws of evolution by intelligent design. “Tinkering with our genes won’t necessarily kill us. But we might fiddle with Homo sapiens to such an extent that we would no longer be Homo sapiens”. (p. 404)

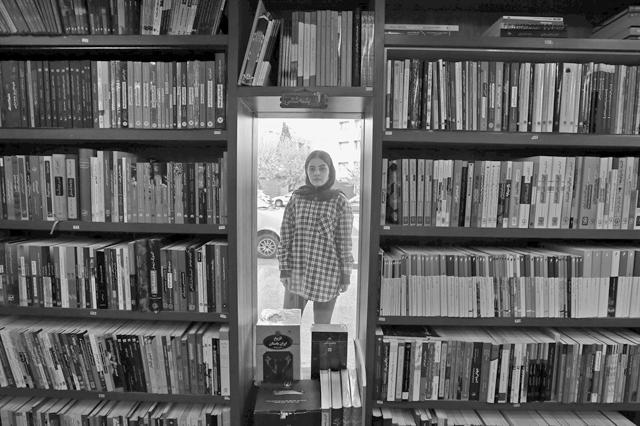

Depending on one’s own philosophical inclination, one might find Harari either terribly cynical or brilliantly visionary. In a very interesting interview included after the main text, he explains how his personal ethics connect to his view of history. “Sapiens” is available at Books@cafe.

Related Articles

TEHRAN — French authors Albert Camus and Simone de Beauvoir rub shoulders with the likes of Jewish diarist Anne Frank and Russian poet Osip

MAROPENG, South Africa — Palaeontologists in South Africa said on Monday they have found the oldest known burial site in the world, containi

PARIS — One of the oldest known Homo sapiens fossils may be more than 35,000 years older than previously thought, according to a recent study that used volcanic ash to date the find.