You are here

Cyprus in Late Bronze Age: Trade routes, settlement patterns

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Oct 17,2024 - Last updated at Oct 17,2024

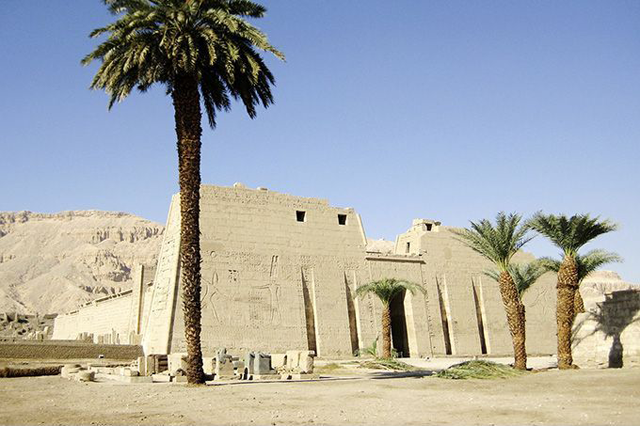

Reconstruction of the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III in Medinet Habu (Photo courtesy of Rosemary Robertson)

AMMAN — Due to its geographic location, Cyprus played a significant role in trade during the Late Bronze Age. The island has been located between Anatolia and Syria and a Hittite document dated to the age of king Suppiluliuma II records that Alasiya (or Cyprus) was annexed to the Hittite Empire, for the first time, at the age of Tudhaliya IV.

This king concluded a treaty with one of his Syrian vassals, the King Sausgamuwa of Amurru, in order to set up a mercantile embargo against the Assyrians, his main enemies.

In the same document, Tudhaliya IV ordered Sausgamuwa to block trade between the ships of Ahhiyawa, also enemies of Hatti, and the Assyrians, seeing that the goods could pass through his territory.

Ahhiyawa was the Hittite term used to designate the Achaeans or Mycenaeans, who were also the Ekwesh included in the first wave of Sea Peoples. Their homeland was not located in Anatolia but in Europe, in the western coasts and islands of the Aegean Sea.

"This means that all the groups of the coalition [Ekwesh, Teresh, Lukka, Sherden and Shekelesh] were peoples of Aegean origin," said Carlos Moreu, a Spanish historian specialised in the collapse of the Bronze Age.

The Sea Peoples was a heterogenous coalition of different ethnic backgrounds.

Based on their outfit, scholars managed to reconstruct who they were and did they come from south-eastern Europe or Asia.

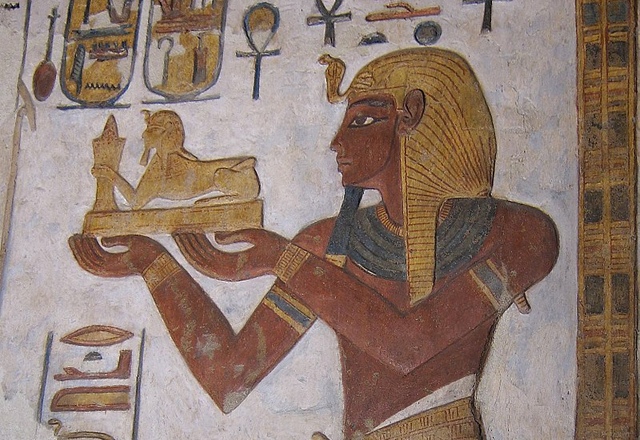

"The Ekwesh warriors were not depicted by the Egyptians in the wall reliefs of Medinet Habu, because they did not participate in the second attack on Egypt by the Sea Peoples, dated to the age of Ramesses III," Moreu said.

He added that the Achaeans were depicted in several frescoes and vessels found in Greece and, therefore, is known that their weapons and clothes were generally different from that used by the Asiatic Sea Peoples.

It is possible that a fragment of papyrus, found in Amarna, represents Mycenaean warriors, using their typical helmets made of wild-boar tusks, but the illustration is not very clear.

Moreu continues that in this papyrus, the unknown warriors appear to fight on the side of the Egyptians, perhaps as mercenaries.

Amarna was dated to 14th century BC where political relations existed between Egypt and Mycenaean Greece. Cyprus was also the Mediterranean centre of copper production and a commercial hub.

"The archaeological research in Cyprus indicates that, in the late 13th century BC, two new settlements were built in the coasts of Cyprus, named Maa-Palaeokastro and Pyla-Kokkinokremos, and both had a brief but dense occupation.

Their foundation can be considered contemporary to the reign of Pharaoh Merneptah, and consequently to the first wave of Sea Peoples," the historian said.

Therefore, it cannot be dated to the age of Ramesses III and the second migratory wave, which was more important.

Maa is located in a small peninsula of the western coast, north of Paphos, and Pyla is a fortified settlement situated nearly the south-eastern coast, 10 kilometres east of ancient Kition and 20 km southwest of Enkomi.

“The establishment of these settlements was clearly a deliberate and planned enterprise, and most cultural innovations that were introduced by its inhabitants came from Mycenaean Greece, such as loom weights, bathtubs, hearths and cyclopean walls,” Moreu said.

He added that Aegean IIIB pottery, both Mycenaean and Minoan, have been found at these sites, including cooking pots, as well as Cypriot, Anatolian and Canaanite ceramics.

"The Anatolian Grey Ware, for example, which is typical of north-western Anatolia, is also present in both settlements [but in small quantities], and we know that north-western Anatolia was a plausible homeland for the Shekelesh and the Teresh," Moreu underscored.

The historian noted that among the newcomers, however, the most numerous must have been the Achaeans, who were also the most numerous warriors of the Sea Peoples at the battle of Perire, according to the Egyptian sources.

The maritime trade was developed in the Late Bronze Age, so goods from the Levant and Cyprus were transported to Sardinia.

Moreover, the foundation of fortified settlements in Crete may have provided the Sea Peoples some bridge heads for their raids and migrations to other areas of the eastern Mediterranean, seeing that there was a general unrest in central and southern Greece during that period, Moreu claimed.

He pointed out that the trading routes had also become insecure after the mercantile embargo imposed by the Hittite King Tudhaliya IV, and this was a plausible reason for the alliance of the Aegean SeaPeoples.

"Crete is well situated in the western route to the African coast and also in the eastern route to Cyprus and the Levant. We know that Pyla-Kokkinokremos had a short life [perhaps 20 years] and its final evacuation must have occurred when the Hittites and their Syrian allies gained control of Cyprus for the second time," the historian said.

The initial settlement of Maa-Palaeokastro was also abandoned, but this site had a second phase of reoccupation in the 12th century BC, after the general invasion of the island by the Mycenaean Greeks that took place at the age of Ramesses III, Moreu concluded.

Related Articles

AMMAN — The Sea Peoples are often blamed for the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisation.Such opinion was particularly popular among researc

AMMAN — The Late Bronze Age collapse brought a dramatic societal change in the Southern Europe, North and South Levant.

AMMAN — The Late Bronze Age was a period of connectivity between different political centres in the Middle East, North Africa and southern E