You are here

Bronze Age collapse: Exploring new insights on Sea Peoples

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Oct 15,2024 - Last updated at Oct 15,2024

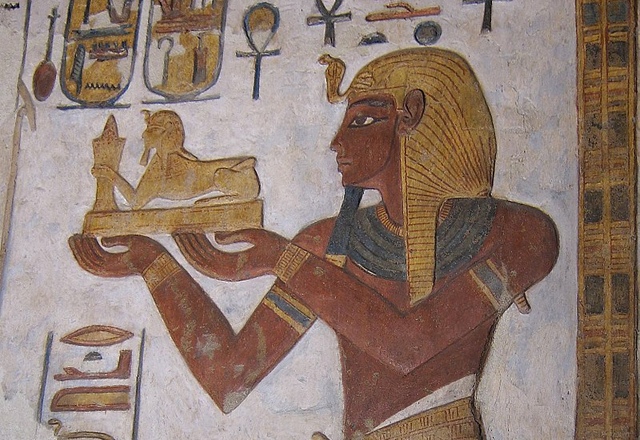

Relief from the Sanctuary of Khonsu Temple depicting Rameses III (Photo courtesy of Asavaa)

AMMAN — The Sea Peoples are often blamed for the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisation.

Such opinion was particularly popular among researchers from 19th century and early 20th century.

However, historiography and archaeology reach other conclusion in the most recent period and the collapse attributed to a series of different societal events.

According to Egyptian sources, the Sea Peoples or “the countries of the sea” attacked Egypt on several occasions between the 14th and 12th centuries BC.

The main attempts of invasion occurred in year five of Merneptah and year eight of Ramesses III, when two different coalitions confronted the Egyptian army in the Nile Delta.

Although both coalitions were defeated by the Egyptians, the archaeological evidence shows that they managed to settle in some areas of Canaan, usually controlled by the Egyptians and therefore two waves of Sea Peoples’ migrations took place in the eastern Mediterranean.

Libyan tribes also attacked Egypt from the west and we have the Great Karnak Inscription, the Athribis Stela, the Cairo Column and the so-called Hymn of Victory as evidence of this turbulent event.

From these texts, it is deduced that a ruler of Libya named Meryey, son of Ded, had invaded the African land of Tehenu with the help of a league consisting of five Sea Peoples. Later, and probably taking advantage of their numerous forces, the Libyans attacked northern Egypt from the west, together with the same allies, but were vanquished by the Egyptian army in the battle of Perire.

According to the Egyptian reports, the army of the pharaoh killed and captured thousands of enemies.

The first lines of the Karnak Inscription names the five groups of Sea Peoples in the following text: “Ekwesh, Teresh, Lukka, Sherden, Shekelesh, Northerners coming from all lands”.

“It is generally agreed that the Lukka were the inhabitants of Lycia, in south-western Anatolia, during the Late Bronze Age.

The Hieroglyphic Luwian inscription of Yalburt, found in Turkey, dates to the age of the Hittite King Tudhaliya IV [13th century BC] and it mentions the land of Lukka together with four towns that have undoubtedly identified as Lycian cities which survived in later times with very similar names,” noted Spanish historian Carlos Moreu, adding that the Lukka was already cited in one of the Amarna letters, reporting that they raided Cyprus and Egypt during the 14th century BC.

This letter was sent by the king of Alasiya (Cyprus) to the Pharaoh. And we also know that the Lukka, recruited by the Hittites, fought against the Egyptian army of Ramesses III in the battle of Kadesh, together with other western Anatolian groups coming from the lands of Arzawa and Masa, Moreau explained, adding that it is very likely that the five Sea Peoples named in the Great Karnak Inscription, who were “northerners coming from all lands”, had their original homelands in Anatolia and the Aegean Sea, which are precisely located in the north-eastern Mediterranean.

It is less plausible, however, that some of these groups came from the central Mediterranean, a hypothesis firstly expounded by E. de Rougé and F. Chabas that was mainly based on the similarities of the ethnonyms Teresh, Sherden and Shekelesh with the names of the Tyrrhenian Sea, Sardinia and Sicily.

In fact, there are other ancient toponyms in Asia Minor, recorded during the Bronze and Iron Ages, which are also very similar to the names of those Sea Peoples, such as Taruisha and Tyrrha (related to the Teresh), Sardis and Sardena (related to the Sherden) and Sagalassos, the river Shekha and the river Sagaris/Sakarya (related to the Shekelesh).

“The maritime trade during the Late Bronze Age, and the final settlement of Aegean colonists in Sicily and Italy, including the Anatolian ancestors of the Etruscans, would explain the similar toponyms found in the central and the eastern Mediterranean,” Moreu said.

Referring to the Sea Peoples, the pharaoh stated: “Their chief is like a dog... bringing to an end the Pedetishew, whom I caused to take grain in ships, to keep alive that land of Kheta”.

The term Pedetishew may refer to an Anatolian region called Pitassa by the Hittites, the scholar maintained.

Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses III (ruled 1186 to 1155) fought with the Sherden and their captive warriors were recruited in the Egyptian army and thus they fought three years later in the battle of Kadesh.

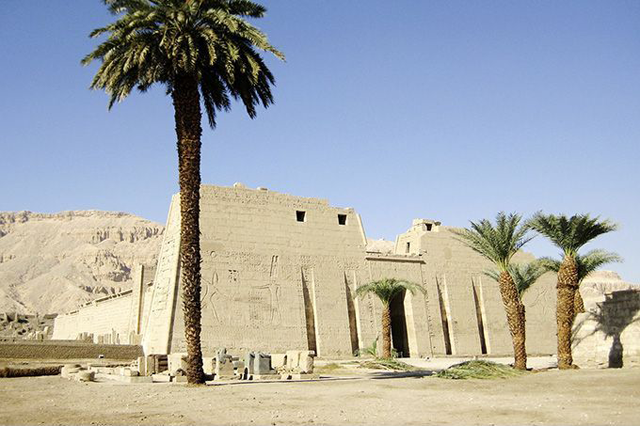

In the 12th century BC, the Sherden fought as auxiliary troops of the Egyptian army and they are depicted in the wall reliefs of Medinet Habu, the mortuary temple of Pharaoh Ramesses III.

“In most scenes, they are of a similar appearance to that of other Sea Peoples depicted in those reliefs.

They wear the same kind of skirt, and they are armed with round shields and the typical swords of triangled blade, also used by the Sea Peoples who confront the Egyptian army in the eight year of Ramesses III.

“The warriors of the invading Sea Peoples, including the so-called Peleset or Philistines, usually are depicted with a helmet crowned with feathers or, more probably, with leather straps.

However, there are other warriors in this second wave of Sea Peoples that also used horned helmets, but they have not the disc at the top,” Moreu highlighted.

The outer look of the Sea Peoples is west Asian, indicating their Anatolian origin.

However, they may have visited or colonised some areas of these islands, during the Early Iron Age, giving their names to them.

This would explain the bronze statuettes found in Sardinia, dating to the Iron Age, which show warriors with horned and “feathered” helmets, the latter very similar to that used by the Peleset or Philistines, Moreu explained.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Due to its geographic location, Cyprus played a significant role in trade during the Late Bronze Age.

AMMAN — Many historical sources about the Late Bronze Age on the territory of the modern Jordan come from Egyptian archives.The oldest relev

AMMAN — After recent torrential rains, the Ottoman mosque of Sheikh Khalilat Al Turrah, near Ramtha, was seriously damaged and one of its wa