You are here

Documenting an Empire: Ottoman archives’ impact on archaeology

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Aug 26,2024 - Last updated at Aug 26,2024

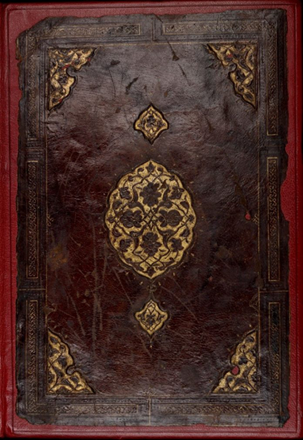

An example of leather bookbinding from an Ottoman manuscript (Photo courtesy of the Ottoman Manuscript Collection of Safvet Beg Basagic)

AMMAN — The Ottoman Empire was strongly bureaucratised, which resulted in a plenitude of written sources.

This generated a high volume of paperwork and distributing copies of nearly every document to provincial and local administrators.

“Its religious scholars and literati wrote copiously,” noted the professor Bethany Walker from The Bonn University, adding that the “pax Ottomana” of the 16th and 17th centuries made it possible to travel the length and breadth of the Mediterranean-wide empire with greater ease and safety than had existed during the preceding centuries of Islamic rule.

“The imperial and many provincial archives, as well as the imperial and many private libraries, have remained intact until today and as a result, archaeologists of the Ottoman world have access to the same range of documentary and narrative sources as archaeologists of mediaeval Europe and the New World,” Walker underlined.

These documents included tax registers (tapudefters), endowment documents (vekfiyes), fixed price registers (narhdefters), yearbooks (salnamehs), chronicles, and garrison rolls to diplomatic documents and records of European consulates, monastic and church records and correspondence, travellers’ accounts, Venetian cadastral maps, land registers and memoirs.

“To this should also be added archaeologically retrieved documents, such as inventories and bills of sale from merchants’ homes and customs houses.

The most important genres of textual sources for archaeological study of the Ottoman world are, by far, tax registers, court registers [sijillat], and fatwa manuals [of legal opinions],” Walker said, adding that for some regions of the Ottoman Empire, such as the Jerusalem area and regions of the Balkans (Rumelia), complete series of court documents spanning centuries are extant, making possible the study of the long-term impact of fiscal and legal reforms, real-estate exchanges, and migration.

The sijillt, in particular, include registration of land sales that record in detail the location and size of cultivated fields, orchards, and gardens, their cropping, land prices, and names of buyers and sellers.

Combination of archival evidence with archaeological and archeobotanical sources provide researchers with more pieces of that mosaic.

Purely archaeological contributions to the study of the Ottoman Mediterranean have, until very recently, not kept pace with historical studies.

The many and complex factors behind the marginalisation of the study of the Ottoman period in archaeological circles, the poor preservation and visibility of Ottoman levels at archaeological sites, and a certain degree of hostility to this period of national history and imagination, in general, have been an issue, according to the scholar.

“Scholarship on Ottoman material culture was long the prerogative of art historians, whose contributions to the understanding of colonialism was, and continues to be, tied securely to the study of urban form [the ‘making of the Ottoman city’], urban housing, imperial architecture, and production of and trade in fine glazed wares,” Walker underlined.

These are imperial perspectives on settlement, production and consumption.

What was missing was the local view of the imperial state and the local experience of it. The “rural turn” in Ottoman archaeology, particularly on the pre-Tanzimat era, has been largely fuelled by interest in peasant agency, migration and travel, land use and landscape studies, markets and consumption, the material culture of pastoral nomads, and the marked regionalism and longevity of material culture, ceramics in particular.

Progress in understanding these areas of rural life would not be possible without the integration of textual sources and methods, which has become an integral part of Ottoman archaeology today.

More archaeologists are using a wider range of texts than is usually the case in Islamic archaeology, and the Ottoman historians are increasingly turning to the archaeological record to explore questions related to the structure of local society, consumption, daily life, and the impact of environmental and climatic change, Walker elaborated, adding that taxation and legal documents, in particular, have provided critical source material for identifying the possible economic and political triggers behind changes in settlement, land use and material culture at the household level.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Little attention has been paid to the early Ottoman era, but an abundant collection of documents and records could shed light on the

AMMAN — There has been a boom in studies devoted to the Mamluk period (1250-1517) due to a recent “rural turn” in Islamic archaeology, accor

AMMAN — The Great Arab Revolt Project (GARP) has investigated material remains of 1916-1918 conflict between the Ottoman forces and Arab arm