You are here

Late Neolithic treasures of Jordan: Studying handmade pottery from Basatin

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Jun 05,2024 - Last updated at Jun 05,2024

A slipped and burnished carinated jar from Ein Jarba in Palestine decorated with a human figure made from applied clay. This pottery belongs to Wadi Rabah culture which thrived in southern Levant in 5th millennium BC (Photo courtesy of Forum Ancient Coins)

AMMAN — Located in northern Jordan, Basatin is a site where around 900 shreds were diagnosed from the Late Neolithic. These objects include rims, bases, handles, body sherds with decoration or other surface treatment, carinated sherds, fragments of jar necks or shoulders and a small number of pierced disks.

The Late Neolithic pottery is all handmade, and there is some evidence for coil construction. Although there are some better-made exceptions, in general, the pottery is rather crudely constructed and poorly fired, and is now so fragile that archaeologists generally cannot wash it, Kevin Gibbs from Berkley said, adding that the fabrics are usually soft and brown, yellow or salmon-pink in colour, often with distinct dark or yellow cores.

“Limestone and chalk inclusions are common, with smaller amounts of chert, iron oxides, and quartz, while some sherds show evidence of fibrous temper. All the raw materials needed for pottery production are locally available,” Gibbs continued, adding that the assemblage of Late Neolithic pottery is very fragmented and rims are often too small to stance accurately, but forms appear to include small cups, bowls, hole mouth jars and necked jars. A number of thick, very friable pieces appear similar to tabun fragments, but we have been able to refit some of them into portions of coarse vessels.

Bowls differ in a range of sizes and shapes, including V-shaped ones, rounded or hemispherical bowls, and bowls with vertical or slightly inverted walls that are sometimes carinated, Gibbs elaborated, adding that a small number of rims could derive from everted bowls or perhaps jars with everted necks, while one body sherd is likely from a small bowl with an S-shaped profile.

“Jars are primarily hole mouths and some of these are rather thick and coarse, while others are finer and occasionally decorated with incisions. No clear examples of necked jars occur in the assemblage, although a small number of sherds seem to represent the junction between a jar’s neck and shoulder,” Gibbs highlighted, adding that because of the fragmented nature of the assemblage, some of the rim sherds identified as bowls may actually derive from necked jars.

According to the professor, bases are mainly flat or disk bases sometimes

showing evidence of pebble or mat impressions or thickened with layers of added clay and limited evidence suggests the presence of vessels with pedestal bases.

“Handles include strap or loop handles, usually with oval cross-sections, and some knobs, small ledge handles, and more protruding, triangular or pointed lug handles. In at least one case, a small ledge handle seems to have been located on the interior of the vessel, while another sherd has two tiny lugs or protrusions located side-by-side,” Gibbs elaborated.

The Late Neolithic pottery from Basatin is most similar in form, surface treatment, and decoration to assemblages attributed to the Wadi Rabah culture, a Neolithic culture from southern Levant that dates from 5th millennium BC.

The general absence of evidence for necked jars is a noticeable difference, however and this is likely due, in part, to the poor preservation of the pottery from Basatin, Gibbs underlined, adding that no clear evidence of bow-rim jars in particular has been found at any Late Neolithic site in Wadi Ziqlab.

“The absence of these vessels, which are often considered the most characteristic vessel of Wadi Rabah assemblages, may reflect a local tradition of pottery manufacture, rather than simply poor preservation,” Gibbs underscored.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Tell Shuneh Shamaliyyeh is located in the northern part of the eastern side of the Jordan Valley in Irbid Governorate. The Jord

AMMAN — Excavations at the Tell Rakan archaeological site are contributing to a better understanding of Neolithic settlements in northern Jo

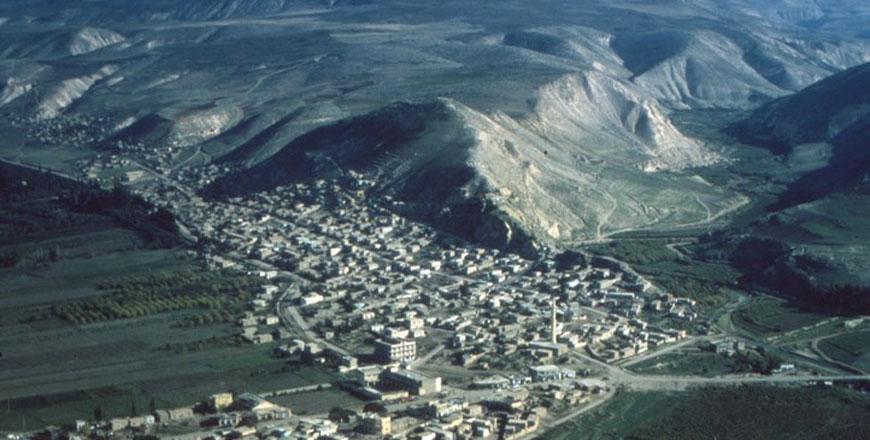

AMMAN — The research in Wadi Ziqlab, located in Northern Jordan, has focused on the distribution and character of small Late Neolithic sites