You are here

Conference hears of ‘the archaeology of olive oil’

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Aug 06,2022 - Last updated at Aug 20,2022

An olive press cut into limestone bedrock at Khirbet Um Al Ghozlan (Photo by Adam Carr)

IRBID — Enclosed sites were specialised processing centres for the cultivation and production of olives and olive oil in ancient times, noted an Australian archaeologist at the 15th International Conference on the History and Archaeology of Jordan (ICHAJ) held at Yarmouk University in Irbid.

“Traditionally, olive oil will be stored for several weeks after olives were crushed and olive oil extracted,” said James Fraser from the British Museum on Tuesday during a presentation titled “The archaeology of olive oil: New excavation of an EB IV olive oil ‘factory’ at Khirbet Um Al Ghozlan”.

Khirbet Um Al Ghozlan, some 14km west of Ajloun, was a model of “horticultural specialisation that interprets enclosure sites as processing centres for upland fruit crops such as olives, and suggests they were enclosed to defend caches of seasonally produced cash-crop commodities such as oil”, Fraser continued.

The Early Bronze IV period (2600-2000 BC) in the southern Levant represented a rural period between the collapse of the first urban centres in the Middle East and the revival of a network of city-states in the Middle Bronze Age (2000-1800 BC), he said.

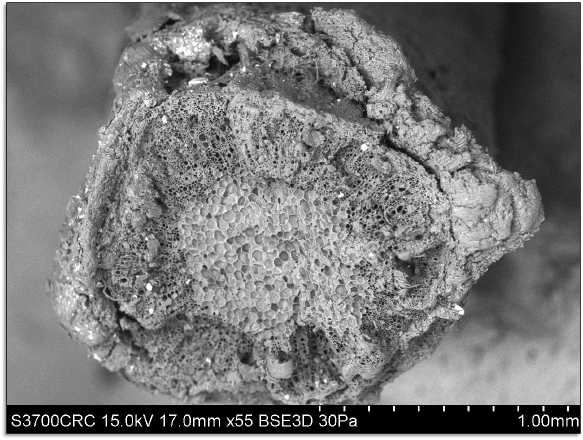

“It’s important to stress that site of Khirbet Um Al Ghozlan lies around 300 metres above the sea level, the slopes were well drained and the site was surrounded by olive trees,” said Frazer, noting that in 2009, he found a few olive presses in the area.

A storage compound was also found at the site as well as 18 jars, which indicated that it was an olive oil manufacturing centre, Fraser said. “The most important discovery was a protecting wall which was utilised for the defence of the site,” he said.

During this period, populations are thought to have dispersed into village communities that practised simple forms of agro-pastoral farming, he said, adding that these rural sites were new foundations on the well-drained slopes of the Jordan Rift Valley escarpment, in areas better suited to the cultivation of upland tree crops than the flood-prone Jordan Valley floor.

Researchers also found a few organic remains like micro-fragments of charred wood, identified as olive wood, Fraser said, suggesting that the site was used seasonally, waste number of olive jars were stored before a distribution of olive oil.

“This research matters because it helps articulate rural complexity following urban collapse,” Fraser said, adding that this methodology proves that rural communities had the capacity for a specialised type of food production in the Bronze Age.

Related Articles

AMMAN — During the Bronze Age, olives became “an integral part of Jordanian social fabric”, having been domesticated in the Levant, then in

AMMAN – The Mediterranean diet has included olives and olive oil from the Bronze Age until modern times.

AMMAN — An enclosure wall that protected three buildings at Khirbet Um Al Ghozlan in Wadi Rayan, some 14 kilometres west of Ajloun, in