You are here

A novel that dwells on the power of the intellect

By Emad Moussa - Jan 24,2022 - Last updated at Jan 25,2022

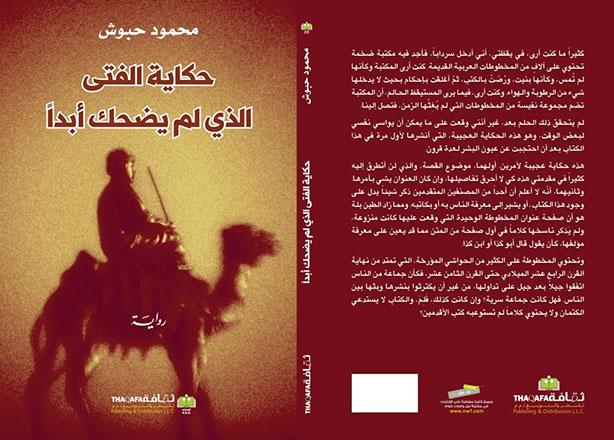

Three years ago this month, Palestinian journalist and novelist Mahmoud Habboush published his debut novel The Boy Who Never Laughed. It is a tale about a boy born in Palestine a few hundred years ago. As a baby, he never cried. And as a child and grown man, he never laughed. Struggling to relate to human emotions and social interactions throughout his life, he nevertheless has an unquenchable thirst for learning. This sets him on a journey that would change his destiny from an outcast in his village to Aleppo’s most renowned scholar.

I have read the novel several times since I published an Arabic review three years ago. Today, on its third birthday, I feel it is time to revisit Habboush’s work yet with a more critical outlook on its philosophical dimensions. Perhaps the novel, called a parable in its Arabic title, is best described as a modern take on Ibn Tufail’s philosophical novel Hayy Ibn Yaqzan, which features a feral boy who grows into a sage in a desert island.

Flicking through the first pages, one is soon overwhelmed with two conflicting feelings of confusion and yearning accompanied by a gust of sympathy towards the protagonist, whom the writer calls “the Boy” throughout the work without ever naming him. As if the author wants us to identify with him, to feel him before even knowing his circumstances. Linking the reader’s emotionality with “the Boy” is perhaps an attempt on part of the author to tell us that “the Boy” is just like us, one of us, and could be anyone we know. This technique is often used to engage the reader with the content and, in this novel, the author has been successful in deploying it.

Modelled on the literary notion of pathetic fallacy, “the Boy” is born amid a storm, in the middle of what can only be described as nature’s wrath. As such, the author prepares us for what comes next, to the unorthodox events throughout the course of the story.

It becomes plain later that “the Boy” is not like other boys in his village. He was born with a permanent frown on his face, somewhat suggestive of the wrathful night that saw his birth. The village inhabitants responded with anxiety and fear. To some, “the Boy’s” unorthodox countenance made him the harbinger of doom, a false prophet who had come to bring evil and destruction to this world. But the message is clear: It may be a curse to be born different in a conservative, close-knit society, much like the majority of Arab societies.

Soon, the frowning boy finds himself on a journey of knowledge and learning. The journey allows the writer, through “the Boy”, to introduce the reader to the rich history of Islamic philosophy. The novel at this point evolves well beyond plain story-telling into the realm of ideas. It becomes immediately apparent that the writer is well acquainted with the major intellectual movements and philosophical schools that flourished during the Golden Age of the Islamic civilisation. He delves into the writings and thoughts of famous ancient Muslim intellectuals, such as Ibn Sina and Al Farabi. Interestingly, he places the readers at the heart of the debate surrounding some of the views of Ibn Hazm of Andalusia, which amount to limiting the power of traditional Islamic clergy. His exposition of Ibn Hazm’s ideas in this regard put "the Boy” at loggerheads with the court’s powerful clerics.

The novel is similar in this respect to Norwegian author Jostein Gaarder’s Sophie’s World without appearing, or intending for that matter, to be a work of education. Gaarder’s novel takes us on an educational journey in the world of European philosophy, from the Greeks to the Renaissance, all the way to the age of Enlightenment and, soon after, modern schools of philosophy. However, missing from Gaarder’s novel is Islamic philosophy in both its original output and Neoplatonic and Peripatetic manifestations. Speaking through “the Boy”, the writer attempts, perhaps unintentionally, to bridge this historical gap. He repositions the Islamic philosophical tradition where it rightfully belongs.

While Habboush’s work is written in the style of medieval Arabic and is riddled with metaphors and allegories, it remains fairly easy to read. The events flow in effortlessly, albeit varying in pace. Presenting the intimate details of “the Boy’s” life is less about giving an insight into “the Boy’s” daily existence and more about inviting the reader to engage philosophically and intellectually. Here, philosophy is introduced in a literary form, a style that is rarely seen in modern Arabic literature.

Of note, the novel suggests that there is a defect in the formation of “the Boy’s” emotional personality. He does not feel or understand the meaning of bliss resulting from laughter, neither does he fathom the complexities of social emotionalities. He is nevertheless fascinated by the social interactions among the people around him. “The Boy”, as the novel reveals to us in its last chapters, understands these social complexities with his mind, yet rarely relates to them emotionally.

Therefore, when he first falls in love with a woman, the feelings are confusing and overwhelming. His body shakes and his hands sweat, but it takes him a while to identify what happened as romantic love. Here, the author gives us a glimpse that love can be a mental state as well. As if to say that love is not necessarily blind, motivated by strong passion and whims only, as it has been popularised in ancient Arabic love stories. “The Boy”, who seemingly suffers from a form of autism, may have been able to find love after all, but in his own way. Born unorthodox, he lived and perceived the world differently, and finding love was inevitably going to follow the same trajectory. Much like Ibn Tufail’s desert island protagonist manages to find God through the study of nature, meditation and introspection, “the Boy” arrives at virtue and love. It is a powerful message that Habboush masterfully delivers in captivating prose.

Related Articles

AMMAN — Palestinian writer Mahmoud Habboush launched his debut novel, titled “The Boy Who Never Laughed”, on Tuesday in Abu Dhabi.

Three Daughters of EveElif ShafakUK: Viking/Penguin Random House, 2016Pp.

AMMAN — Deputising for HRH Prince Hassan, HRH Princess Rahmeh, in the presence of HRH Prince Asem Bin Nayef, on Monday night attended the Em