You are here

Peace reigns in Colombia’s former guerrilla fiefdom

Nov 16,2021 - Last updated at Nov 16,2021

Colombian soldiers of Humanitarian Demining Battalion work inside a minefield laid by guerrillas in Marquetalia, the birthplace of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, Tolima Department, Colombia, on October 27 (AFP photo)

By Herve BAR

Agence France-Presse

MARQUETALIA, Colombia — It all began in a mountainside hovel perched in the Colombian Andes, where peasant soldiers, besieged by government forces, founded the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in 1964.

After 50 years of bloody struggle, and another five since the 2016 peace accords that ended FARC’s battle against the state, this isolated south-central region has rediscovered peace.

FARC, and its war, seem a distant memory in Tolima province, 200 kilometres southwest of Bogota as, where all that remains of the conflict is a few leftover anti-personnel mines and the occasional discreet army patrol.

Although the peace deal is holding, the number of armed groups operating in Colombia is on the rise, yet Tolima is an exception: Here peace reigns.

Tolima and the Marquetalia Valley, remain synonymous, for Colombians at least, with the war, murder and the Marxist FARC guerrillas.

“There were so many awful stories here... it was blood, every day dead bodies, with civilians caught in a vice between guerrillas and soldiers,” said Leonoricel Villamil, a local politician for the small towns of Planadas and Gaitana.

“FARC were at home here, they came down from the mountain, went where they wanted. The soldiers built walls, besieged in their barracks.”

Kidnappings were frequent.

‘A strategic place’

In 1964, the army launched an offensive to take control of several peasant shelters set up following the 1948-53 civil war that had come under communist influence.

On May 27, battle waged in the Ata River canyon in Marquetalia valley, and FARC was born.

Marquetalia would remain its fiefdom.

“Right in the centre of the country, it was a strategic place for us, a corridor between the three mountain ranges that connects the north to the south, close to Bogota,” Pastor Alape, a former FARC leader, told AFP.

Even today, it remains an isolated region that is difficult to access.

To reach the heart of Marquetalia involves a treacherous journey along a dirt track either by motorcycle or powerful old Russian trucks.

Next is a two-hour ride on horseback up steep slopes, followed by a trek on foot, knee high in mud and soaked by rain.

The spectacular views makes the ordeal worthwhile: Majestic mountains covered in tropical vegetation, all in the shadow of the snow-capped Nevado del Huila volcano.

Cows graze on the hill where FARC was born. Having been briefly occupied by the army, the pastureland is now owned by a farmer.

“FARC controlled everything with severity,” said Alberto Colorado, a peasant who lost five brothers that were “forced” to join the communist rebels before being killed by the army.

“You had to adapt and obey. Everyone was afraid,” he added, sporting a machete in his belt and a parrot on his shoulder.

Beans instead of poppies

“All this is ancient history, everything’s changed,” said Hector Almario, 27, a local community leader. “Here there is peace, we move about freely day and night.”

“No-one is coming to kill or bombard us any more, we live in a little paradise,” said a smiley Bellanith Cumaco, 44, another local leader.

The entire community meets in the village’s only school — an old rebel headquarters.

Marquetalia, is made up of 19 families, said Almario, who live off cattle, cheese and red beans.

Gone are the poppy crops — the primary ingredient in heroine — that abounded under FARC.

There are still disputes, most commonly over access to land, but they don’t descend into violence in Marquetalia.

‘Abandoned’

At the end of the working day, de-miners attempting to clear the last unexploded anti-personnel devices left over from the conflict, join locals to play football on the school grounds.

On the peaks nearby are stationed some discrete soldiers.

“Sometimes there are rumours” about armed groups advancing along the mountain range from the Cauca department to the southwest, looking for recruits.

“We’re afraid that the state will leave us to face all these people alone,” said Almario.

One complaint echoes around the mountains.

“Our problems are the roads, the trails, the bridges... and the absence of the state,” said Cumaco.

For Villamil, the area has “always felt abandoned by Bogota”.

Since the peace deal was signed, some new paint for the school’s walls is “the only help we’ve had from the state”, said Almario.

The residents club together to save money for community expenses.

“We do everything ourselves, including maintaining the trails and the attempt to build a road. We have many needs but we have to do everything by horseback. It costs a fortune,” said Cumaco.

Tourism potential

FARC has lost all support in these parts where locals want to “change the constantly negative image” of their home.

What is left of FARC in Marquetalia is just the families of around 100 disarmed former guerrillas, who live lower down the valley in a “reincorporation” village.

Images of legendary FARC leader Manuel “Tirofijo” Marulanda and the red rose emblem of the Comunes political party formed by ex-guerrillas after the peace accord don the walls of houses in Marquetalia.

Ex-fighters are now “integrated” in the area where “other communities have accepted them”, said a local merchant, who requested anonymity.

Some former FARC members want to turn Marquetalia into a tourist attraction to share the history of the Marxist rebellion.

It is not a popular idea in a village that wants to break from its past but Almario acknowledges the subject should be discussed.

“If it helps bring in tourists and changes our image, then why not?”

Related Articles

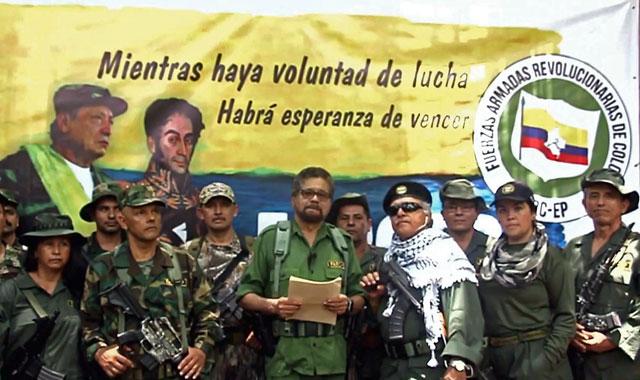

BOGOTA — A former senior commander of the dissolved FARC rebel army in Colombia said on Thursday he is taking up arms again along with other

BOGOTÁ — Four Colombian Army soldiers were killed in fights with FARC dissidents a day before a meeting between the rebel group and the gove

BOGOTA — Leftist Venezuela has agreed to be a guarantor of future peace talks between Colombia and its last guerrilla group, both countries