You are here

German scholar digs deeper into orientalists’ study of Nabataean religion

By Saeb Rawashdeh - Apr 02,2018 - Last updated at Apr 02,2018

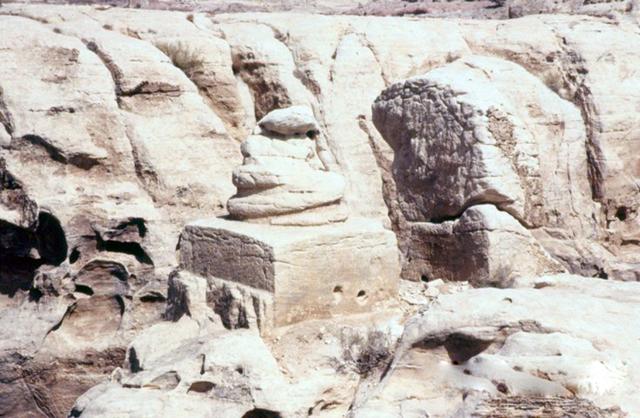

Obodas Theos, a Nabataean deity in Petra (Photo courtesy of Robert Wenning)

AMMAN — Orientalists R. E. Brünnow and Gustav Dalman focused their early 20th century research (1904, 1908 and 1912) on documentations of monuments in Petra, providing fine observations and interpretations, said Robert Wenning, who received his PhD in classical archaeology from Munster University.

While Brünnow studied the tombs' facades, Dalman researched the smaller rock-cut installations, he explained, adding “Dalman started his chapter on the Nabataean religion with the epigraphical evidence on the deities, followed by a discussion of the documented material evidence like ‘idols’, altars and holy sites, among others."

Epigraphic sources

According to Wenning, this study could have been a promising start to describe the religious practices of the Nabataeans based on archaeological evidence, "but it failed to happen".

“When excavations were carried out in the centre of Petra between 1958 and 1965, new interest in the Nabataeans and their religion developed,” the German scholar explained noting that it resulted in an article by Jean Starcky titled “Pétra et la Nabatène” in the 1966 “Dictionnaire de la Bible Supplément VII”.

Starcky was an expert in Aramaic languages, so it is not surprising that he relied on the Nabataean epigraphic sources, Wenning elaborated.

At the opposite of Dalman, Starcky put together the complete epigraphic evidence for each deity to provide more information on each god, fitting the needs of a dictionary. He noted that the compilation was taken as the basis of interpretation of the Nabataean religion in general, although the sources come from quite different areas of the Nabataean kingdom and belong to different periods and contexts.

Furthermore, Starcky did not include the broad archaeological evidence presented by Dalman and previous experts, depicting a seemingly homogenous Nabataean religion, which did not exist in real life, Wenning highlighted.

‘Unique approach’

For Wenning, director of the project “The Gods of the Nabataeans”, it is crucial to develop a specific personalised approach to define the Nabataean religion. “When I started the project in 1995, the need for a better understanding of the betyls became very clear,” he said.

In a systematic survey on the votive niches carried out over several years, Wenning documented more than 850 betyl niches in the eastern part of Petra, three times more than those listed by Dalman listed.

Wenning maintains it is necessary to focus more on the monuments themselves, analysing and describing them in great detail. “I prefer to research the local evidence first before I take the common features from the various Nabataean sites for a Nabataean religion,” he said.

While the epigraphical evidence is well-studied, figural representations of Nabataean deities and other religious motifs remain under-researched.

“The same few sculptures are repeatedly shown in exhibitions and publications because of their quality and good condition, among other reasons,” Wenning claimed, stressing that “various sculptures depicting Greek deities, which were thought to be in reality representing Nabataean deities, could be identified as Greek motifs without a direct relationship to Nabataean deities”.

The sculptures are not only representative monuments of the Nabataean elite, but also products of the simple craftsmen, workers and citizens, he said.

Regarding future plans, the veteran archaeologist said: “After completing this analysis, there will be some new insights into the aspects of the local religion. I then plan to investigate some of Dalman’s ‘sanctuaries’ and other installations.”

Related Articles

AMMAN — A team of scholars from Bonn University started a project “The Gods of the Nabataeans” whose objective was to study the pantheon of

AMMAN — Petra’s Snake Monument in the southern part of the rose-red city offers clues to the role of serpents in Nabataeans religious practi

AMMAN — Within Nabatean polytheism, the importance of the Nabatean god Dushara increased with the political and economic development of the