You are here

‘Truth-telling was a hazardous business’

By Sally Bland - Oct 23,2016 - Last updated at Oct 23,2016

The Illuminator

Brenda Rickman Vantrease

New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2005

Pp. 406

Although its time span is only a few years, “The Illuminator” has an epic quality due to how Brenda Rickman Vantrease situates the story in a panoramic view of English life and history in the late 14th century. It is a time of transition and brewing conflict: Cracks are opening in the old feudal order. Bishops and nobles jostle for power, taking advantage of the youth of King Richard.

There is mounting popular resentment of the social inequality upheld by the crown, the nobility and the church, claimed to be the Divine Order. The English language spoken by commoners is asserting itself in relation to the aristocracy’s preference for Norman French and the church’s Latin liturgy. John Wycliffe is doing the first translation of the Bible into English, to make it more broadly accessible, while renegade priests are railing against the church’s wealth and abuses.

Crisis hits when the crown and the church increase taxes and tithes to subsidise their opulent lifestyle and foreign wars fought in the name of religion. Coming on the heels of the plague which had already aggravated the miserable conditions and overwork of the poor, this ignites the 1381 Peasant Revolt and its violent suppression, signalling the climax of the novel, and spelling the demise, or nearly so, of its major characters.

From the first pages, the author thrusts us into the burning questions and material reality of the day: Sugar is rare and expensive, as are candles; the poor may choose to watch their children starve, or sell them into servitude; those who appear to be different are subject to ridicule, or worse; while speaking out against injustice may land one in a dungeon, or the hangman’s noose. “Truth-telling was a hazardous business.” (p. 185)

The story centres on an aristocratic family surrounded by servants, serfs and peasants on their estate, but the point-of-view is greatly broadened by their encounters and friendship with singular personages of contrasting backgrounds, chiefly a dwarf, a peasant girl and an anchoress, both gifted with visionary powers, and Finn, the illuminator. While the king, Wycliffe, the revolt leaders, the anchoress and a venial, conniving bishop are based on real historical figures, the rest are creatures of the author’s imagination, so vividly well-drawn as to remain in the reader’s mind long after closing the book.

Still beautiful at 40, Lady Kathryn of Blackingham Manor is recently widowed, though not grieving for Sir Roderick, her overbearing, insensitive husband. Mostly she is worried about preserving the estate so that her two sons may inherit it. She is painfully aware of women’s limited rights. Financial ruin or any smudge on her reputation can give cause for the manor to be taken from her, and predators are already lurking, from greedy priests peddling indulgences that drain her dwindling resources, to false suitors coveting her land. Not the pliable female preferred in patriarchal society, she is determined to run the estate wisely and steer clear of the prevailing power struggles, but a series of conspiracies and accidents of fate cloud her prospects.

Seeking protection and public proof of her piety, Kathryn agrees to an abbot’s request to host Finn, the artist who is illuminating the Gospel of Saint John for his monastery. Since Finn has a marriageable daughter, it is not be suitable for them to live with the monks. The entry of the illuminator and Rose breathes fresh air into the manor house. Strong but gentle, brave but compassionate, with an acute sense of social justice, and infinite charm, Finn eschews unnecessary violence and false piety. In his view, “There is no such thing as a holy war”. (p. 15)

He is the antithesis of Sir Roderick and the entire lot of scheming, violence prone nobility and corrupt bishops. Like Kathryn, he seeks balance in religion, for he has tasted “the dark underbelly of piety” that almost destroyed his life. (p. 43)

They fall in love, and Kathryn finds the pleasure that was lacking in her marriage, but Finn has secrets that complicate her situation. One is that he is also illuminating Wycliffe’s translations, considered heretical by the church.

The feminism implicit in Kathryn’s strong will, and the genuine piety so lacking in the top clergy, find full expression in an anchoress who, like Finn, exemplifies major themes in the story. Believing that God’s love for humans can only be compared to a mother’s love for her child, she postulates the concept of a Mother God, presaging some modern feminist ideas. (The anchoress is inspired by Julian of Norwich, whose “Divine Revelations” is the first book written by a woman in the English language.)

By mixing history with fiction, and humanistic values with adventure, Vantrease has concocted a powerful novel full of passionate and saintly love, corruption and purity, kindness and treachery, noble human intentions and cruel fate. The book is obviously well researched, containing fascinating details about the cuisine, architecture, agriculture and costume of the times, not to mention the derivation of the colours used for the illumination of manuscripts. It would make a beautiful and exciting film.

Related Articles

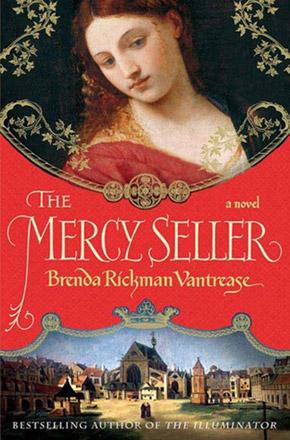

The Mercy SellerBrenda Rickman VantreaseNew York: St.

CAIRO — An Egyptian court on Saturday sentenced two monks to death over the murder of a bishop, a judicial source said, in a case that shock

HRH Prince Hassan issued a statement on Tuesday on the second anniversary of the kidnapping of Greek Orthodox Bishop Boulos Yazigi and Syriac Orthodox Bishop Yohanna Ibrahim in Aleppo.