DUBAI — Iraq plans to establish a state-funded investment bank to help finance big infrastructure projects and steer money towards private sector companies which need it, a senior government official said on Monday.

An underdeveloped, inefficient banking system has hindered efforts to mobilise funds for investment in Iraq. Bankers at a financial conference in Dubai on Monday described how some Iraqi corporate executives carried around tens of thousands of dollars in cash to settle transactions that are too inconvenient to do through the banking system.

“We need this [state-funded investment bank] to push forward the economy,” Sami Al Araji, chairman of the National Investment Commission, told Reuters on the sidelines of the conference. “Our existing commercial banks do not have the skills or experience.”

The new institution, Investment and Development Bank of Iraq, would receive 1 per cent of annual state budget allocations over seven years under a proposal that will be sent to parliament for approval, he said.

That arrangement, if it goes ahead, could eventually provide the new bank with over $10 billion to invest; this year’s state budget is estimated at 174.6 trillion dinars ($150 billion).

Despite the militant violence plaguing Iraq, the economy has managed to keep expanding on the back of oil output; the International Monetary Fund forecasts annual gross domestic product growth of more than 6 per cent from 2014 to 2018.

Iraq already has 23 private conventional banks and nine private Islamic institutions, as well as seven state banks and 16 foreign banks operating in the country, according to the central bank website.

Araji said a dedicated investment bank could participate in financing some of the tens of billions of dollars of infrastructure projects which the government plans over the next several years.

It could also help arrange funding for small and medium-sized enterprises, which authorities want to develop to create jobs and diversify the economy beyond oil.

The proposal for the investment bank is part of a series of planned amendments to investment laws which will be submitted to parliament, Araji said. A parliamentary election is scheduled for April 30, so the proposal would probably be considered by Iraq’s next parliament.

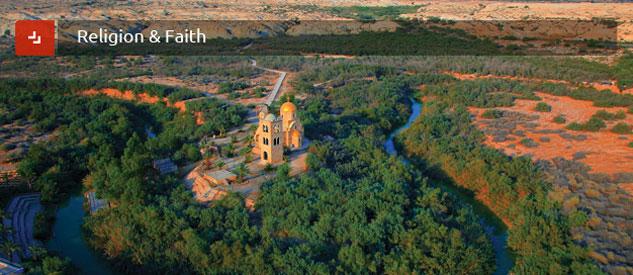

Separately, officials in Baghdad want to promote tourism and believe visitor numbers can be increased threefold.

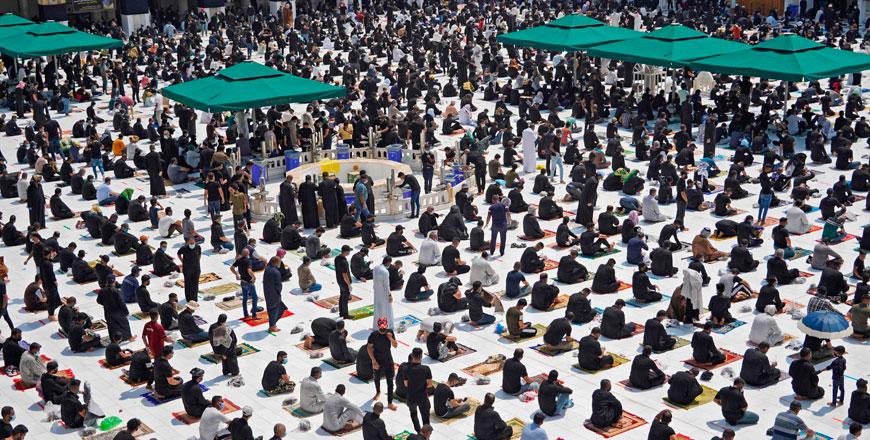

Though almost entirely dependent on oil exports for government income, the government wants to ease a reliance on Iranian pilgrims — most of the population of its enormous eastern neighbour is Shiite Muslim pilgrims annually who visit its multiple shrines and holy sites, from Samarra in the north to Basra in the south.

While tourists must struggle through Iraq’s decrepit infrastructure and often-frustrating bureaucracy, including a difficult-to-navigate visa system, a handful of tour operators is bringing groups to the country.

“Every area that we’ve been to has been totally, totally, different,” said Lynda Coney, one traveller on a trip organised by Britain-based Hinterland Travel.

“The Arab people, history, the archaeology... have absolutely grabbed me with interest,” the Briton told AFP while trudging through Baghdad’s main railway station.

Since 2009, Hinterland has been taking visitors on tours of Iraq lasting nine and 16 days, with prices starting at around $3,000 (2,265 euros) for the shorter trip, plus flights and visas.

The group travels in an unmarked air-conditioned van with Geoff Hann, Hinterland’s owner who has himself been making trips to Iraq since the 1970s, an Iraqi policeman for security, and a small team of drivers and guides.

They mostly try not to be noticed, do not announce where they are staying or headed, and generally have low-profile security.

By contrast, officials, diplomats and foreign company staff typically travel in heavily armed convoys of vehicles with tinted windows that zoom through Baghdad’s streets.

They travel from Iraq’s north, where they take in the ancient cities of Nimrud and Hatra, down through Baghdad to Babylon and on to the port city of Basra, before returning to the capital.

While in Iraq, Hinterland customers stay at hotels, though the quality of the establishments varies enormously. None of the tourists who spoke to AFP expressed any complaints about accommodation.

Hann’s tour operator is one of the few that has approval from the government to organise trips. Individual tourists often struggle to obtain visas to the Arab-dominated parts of the country.

Much of Iraq’s security-focused infrastructure is ill-prepared for Western tourists.

While moving through Baghdad, for example, Hann’s group was stopped at a checkpoint outside a cemetery, with federal policemen demanding authorisation papers, typically only required of journalists, from the capital’s security command centre for the tourists’ cameras.

For “most of our tours under the Saddam Hussein dictatorship, we were restricted with minders”, Hann said.

More recently, “it’s been difficult here because of the security situation. We’ve had to have a different sort of minder”, he added, referring to the policeman escorting the group.

“That’s still there, it hasn’t gone away, because the security position for everybody here is difficult,” Hann noted.

Officials admit that while they hope to promote tourism, they also lack the funds for advertising campaigns, since much is budgeted for physical reconstruction after decades of war, and resources are also lost to widespread corruption and incompetence.

Visas, meanwhile, are the domain of security officials, who are loathe to reform a complex system that prioritises entry permits for pilgrims over other tourists.

But that is all almost academic when compared to Iraq’s main problem — its reputation for poor security.

The country has been through decades of conflict, from the 1980-88 war with Iran to the bombings and shootings that continue to plague daily life.

“When Iraq is mentioned in Europe, the first things that people think of are terrorism and violence,” Baha Al Mayahi, a senior adviser to the tourism ministry, said.

“We need to put in place major efforts in order to change this, and to tell people that Iraq is not terrorism and killing, that Iraq is history and civilisation,” he added.

Mayahi said Iraq averages around two million tourists annually, but that with some basic improvements that figure could increase to six million.

By contrast, Hong Kong, with a population less than a quarter the size of Iraq’s, brought in more than 48 million tourists in 2012, according to its official data.

According to Zein Ali, a worker at a private house cleaning company, an influx of foreign tourists would help change Iraq’s image.

“I think tourists should come more often. There is violence here of course, but you can be killed anywhere in the world,” Ali remarked.

“Baghdad is not how we see it on TV. Tourists should come here, see this city, and I am sure they will come back again,” the 21-year-old said.

But the violence if anything appears to be worsening, with a surge in attacks and car bombings in recent months hitting much of the country. Although Hinterland is planning more trips, Mayahi admitted that security problems could scupper plans to promote tourism.

“If security worsens, tourism will decrease,” he said.

Despite the difficulties, few on the Hinterland tour expressed reservations about their trip.

“For a long time I’ve really wanted to come here,” said Greg Lessenger, a 32-year-old from Washington state in the United States. “There was no possible way for me to go travelling [to Iraq] on my own. But then I found out about this, and I thought, maybe I have got a chance, and I took advantage of it.

“If you’re a real traveller, you have got to see some of these places,” he added.