“There, I met Gerald Lankester Harding, who had been director of Antiquities of Jordan between 1936 and 1956 and was a world expert on the inscriptions and graffiti carved by the ancient inhabitants of Jordan, Syria and north Arabia,” Macdonald said, adding that Harding inspired his work on these graffiti.

Macdonald then joined Yarmouk University as a research fellow and set up a project called the “Corpus of the Inscriptions of Jordan Project” which did fieldwork recording inscriptions in the ḥarrah, or “Black Desert”, and created for the university an enormous archive of all known photographs of all types of inscriptions found in Jordan.

“In 1983, I returned to Britain and worked as an independent scholar for some years, before being elected to Wolfson College, Oxford. In 1994, I set up an online database of all the known Safaitic inscriptions [graffiti carved by ancient nomads in southern Syria, Jordan and northern Saudi Arabia]. In 2013–2017 I ran a project at the Khalili Research Centre, Oxford, in which we expanded this database to include all the Ancient North Arabian inscriptions from oasis-dwellers and nomads in southern Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, etc. This is called the Online Corpus of the Inscriptions of Ancient North Arabia [or OCIANA] and currently has just under 45,000 records, with more being added every week,” he explained.

The question remained unanswered as to why the ancient nomads, not only in the Black Desert but in the deserts from southern Syria right across Jordan and western Arabia down to the border with Yemen, learnt to read and write roughly between the 6th century BC and the 4th century AD.

“It was not a useful thing to learn because they didn’t have paper or mobile phones, like their modern successors, and papyrus was expensive outside Egypt, and bits of broken pots [ostraca] which townspeople used as we use paper, weren’t available to ancient nomads since they didn’t carry much, or any, pottery because it got broken. So, their society used memory and face-to-face speech instead of literacy,” said Macdonald, adding that at different times, individuals must have seen someone from a town writing and asked to teach them how to do it.

If the person writing did teach them, the nomad would have gone back to the desert and shown his friends and relatives what he had learnt, probably drawing the letters in the dust and pronouncing them, and since non-literate people have excellent memories, knowledge of writing would have spread very quickly.

“But, because the only things they could write on were rocks — not very helpful if you want to send a letter, or record something if you have a nomadic lifestyle — literacy did not change their way-of-life. The one thing it did provide was something to pass the time while they were alone looking after the goats, sheep and camels while they pastured,” Macdonald explained.

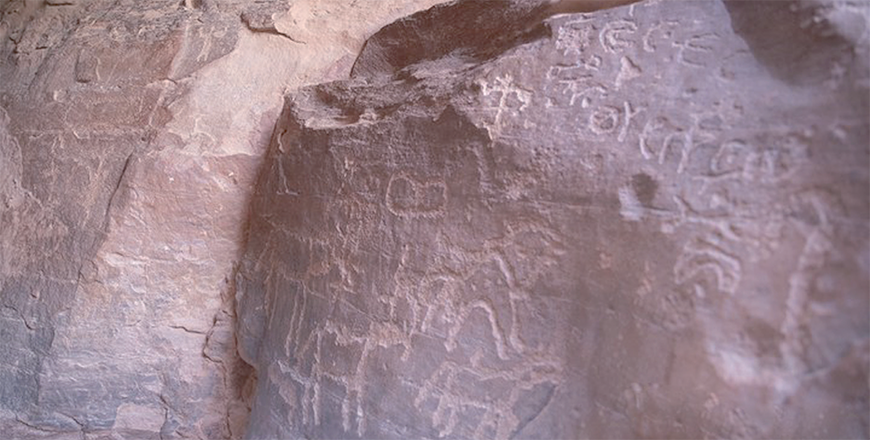

This is how nomads started carving graffiti on the plentiful basalt rocks of the Black Desert. They would start off by carving their names and then as much, or as little, of their genealogy as they could remember or be bothered to carve, Macdonald said, noting that for many it was enough, but others would then say what they were doing (pasturing the camels, helping the goats give birth, building a cairn, migrating, fleeing the Romans, hunting, etc.) or what they were feeling (missing friends and relations, mourning for loved ones, wanting revenge, etc.).

“Finally, some would add a prayer for security, rain, a change of circumstances, etc... Some of these nomads were excellent artists in what is a very difficult medium — if you make a mistake when carving on basalt, it is very difficult to cover it up — and their drawings also give us an insight into their way of life,” Macdonald underlined, adding that because we have such huge numbers of these graffiti and drawings we can build up a detailed picture of the society, way-of-life, and individual feelings of these nomads, which is something we don’t have for the ordinary people of any other ancient society.

Another important point is that the graffiti carved by these ancient nomads were not aimed at a reader. They seem to have been carved to pass the time or as a way of recording emotions, rather like diary, but in a society in which privacy was practically unknown.

“Thus, it can run in any direction, not only right-to-left, but left-to-right, upwards, downwards, round-and-round in circles, in whatever direction was easiest for the carver. The letters are not joined but there are no spaces between words and no vowels of any sort are shown,” Macdonalds said, noting that Bedouins were writing for themselves and although their graffiti were in a public place and they did not care if others read them — as we know they did, because they often left another graffito saying they had!” Macdonald concluded.