On Sunday, the Spanish cultural centre “Instituto Cervantes” in Amman launched an exhibition that will last until September 12. The exhibition presents the drawings and related texts produced by Luis Sarabia, a sailor who witnessed from the first hand the collapse of the Republican army, and the last phase of the Spanish civil war which took place between 1936 and 1939.

His sketches highlight the plight of ordinary people caught between warring parties as well as ports and cities where fighting occurred. The focal point is the port Cartagena, in Murcia, in the south-eastern Spain, and our protagonist is also our narrator: Luis Sarabia.

Born in Madrid in 1910, in the family of sailors, Sarabia's life was interrupted by the Spanish Civil War when he was mobilized and joined the Republican army. Even before the conflict, he showed artistic talent by creating a sketchbook that he dedicated to his fiancé, pointed out Professor Javier Moscoso, from the CSIC (Spanish Scientific Research Council), main curator of the exhibition and the grandson of Sarabia.

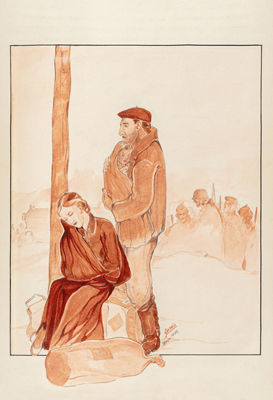

For his drawings he used pencil and sanguine, signing each piece and adding a caption describing each sketch, which enhances the expressivity and value of the drawings. Sarabia drew his own experiences against the backdrop of air raid shelters, hospitals, the port, the coast batteries, soldiers and civilians and their daily hardships, Moscoso added.

The rhetoric resources used by Sarabia, both in his drawings and texts, reflect the visual culture of his time, and a unique poetic capacity to record his personal experience in the middle of the drama of the war unraveling around him, pointed Professor Moscoso. He remarked the fact that “like many other individuals that in times of profound crisis like wars, or pandemics (like recent COVID one), try to record the events they undergo and their experiences, they know how these events and crisis start, but are completely unaware of what will be the development and the outcome of these events portrayed”. Luis Sarabia, who had been unexpectedly mobilized and shifted from a merchant sailor into a one of the Republican Navy, “could have not known when he was swept up by the turmoil of war, what would have been his immediate future, and much less could have known which would have been the outcome of his drawn narration”, Moscoso added.

“It is during these crisis when the lives of normal people become altered by “History” which randomly determines dramatically the survival or death of the protagonists”, commented Juan Vicente Piqueras, Director of the Cervantes Institute which hosts the exhibition. “When wars burst and erupt, crushing the routine of the life of adults and the innocence of childhood, uncertainty and fear reign, and we become pawns of a game that we do not control”, added Piqueras.

Cartagena, the theater of Sarabia’s narration was one of the cities hardest hit by the fascist aviation: In total, the city would be bombed by nazi [the German Condor Legion] and fascist [the Italian Regia Aeronautica] aviation 117 times during the war.

“The visual depiction of the ‘Cartagena uprising’ registered by Luis Sarabia in his drawings and notes, constitutes thus, not only a moving personal memory, but also as a historical document of these dramatic days, a background that determines the personal sufferance, as a result of the development of these momentous events”, underlined Professor Ignacio Arce from the German-Jordanian University, co-curator of the exhibition, who has delved on the historical events, characters and vessels depicted in Luis Sarabia’s drawings.

"The aim was to highlight the link between personal memories of Luis Sarabia and the historical events that became intertwined in his drawings, offering a personal and intimate view of the key historical events from a human being that suffers the consequences of the war," added the curators.

The drawings produced by Sarabia, present his own the fears, concerns and aspirations, mingled with those of the inhabitants of Cartagena, who suffered like few other Spanish cities so many bombardments and hardships during the war, pointed Professor Moscoso. As an expert in Cultural History (he is author of a singular History of Pain, recently translated into Arabic), Professor Moscoso acknowledges that he and his family have learnt to recognize in this unique work of their grandfather, something more than the record of his personal memories: a unique artistic creation, and a remarkable historical document.

“Actually, the ‘Cartagena Uprising’ which Luis Sarabia records in his drawings and notes, was the first act of the so called 'Casadista coup’ that would led to the end of the Spanish Civil war. The ‘Cartagena uprising' was carried out by soldiers and sailors from the Cartagena naval base and broke out on March 4, 1939, two days before Casado's coup (and a month before the end of the Spanish Civil War)”, commented the curators, noting that the Cartagena uprising had been planned and orchestrated by the "Casadistas" with the intention of controlling the fleet in order to negotiate a conditional surrender to the Francoists.

The 'Casadista’ coup d'état was triggered on March 5, 1939, and was led by Colonel Segismundo Casado, head of the Republican Central Army. It was aimed to put an end to the war, against the will of the Spanish Prime Minister, Juan Negrín. Negrín was fully aware that General Franco sought only the unconditional surrender, which also meant certain death for prominent members of the Republican government and military forces, while Casado still thought that there was a room for negotiation with Franco.

“Prime Minister Negrín had intended to resist while waiting for the imminent world war to break out in Europe, which was already seen as something inevitable, despite the fact that, after the fall of Catalonia to the hands of the Francoist at beginning of February 1939, the situation of the Spanish Republic was desperate," the curators pointed, adding that the hope of the Negrín government was that, once war would have been declared by France and the UK against Nazi Germany, the balance of forces in this international arena would have prevented their imminent defeat, and would have gained the military and political support that the European democracies had denied the Spanish Republic for years.

This betrayal and abandonment of the Spanish Republic was partly the result of Daladier’s and Chamberlain's policy of 'appeasement' towards Hitler. They accepted the annexation of Austria first, and of the Czech Sudeten region later, by Hitler, through the embarrassing Munich Agreement.

The coup and the preliminary Cartagena upraising were naively intended to achieve a conditional surrender to Franco, and counted with the collaboration of Franco's espionage networks and the Fifth Column in Madrid and Cartagena. As a result, the republican government of the socialist Prime Minister Juan Negrín was overthrown, but it did not achieve its goal of a conditional surrender, because the Republican fleet, main objective of the uprising, was handed to Franco by the French Authorities, who had recognized his government.

"The loss of the fleet did not only deprived the Republicans of any instrument of resistance or negotiation, but also meant to lose the last chance to escape to thousands of refugees who were fleeing from the reprisals of the Francoist troops” Professor Arce elaborated, “triggering the last episode of dramatic events that sealed the end of the Civil War: the exile and reprisal enacted by the winners.”

“The drawings of Luis Sarabia, which alternates episodes of the extreme living conditions of the civil population, and the episodes of violence of combats and bombardments, gain momentum in the last stages of his narration, with increasing levels of drama and sufferance, which ends with the defeat o the Republican army, and the return of the author with his wife and daughter to Madrid” pointed Professor Moscoso. This would be the final outcome of these dramatic years, which he would never forget.

Professor Moscoso explained out how “the permanent presence of children in the drawn narration of his grandfather, ending with the final scene of that demobilized sailor returning home with his exhausted wife and his daughter in his arms, adds an extra sense of drama and sufferance of humanity in times of war, personified in the shattered innocence of those children”.