AMMAN — For Lebanese artist Annie Kurkdjian, art is the best kind of therapy.

The Beirut-based artist, whose childhood has been scarred by the Lebanese civil war, says that creating artwork to channel her emotions makes her productive, and — as a result — happy.

“When I first started pursuing art within an academic domain between 1994 and 2004, I never felt happy,” Kurkdjian told The Jordan Times.

“Only when I decided to lock myself away from the opinions and comments of others did I find my own voice and my happiness in art,” she said.

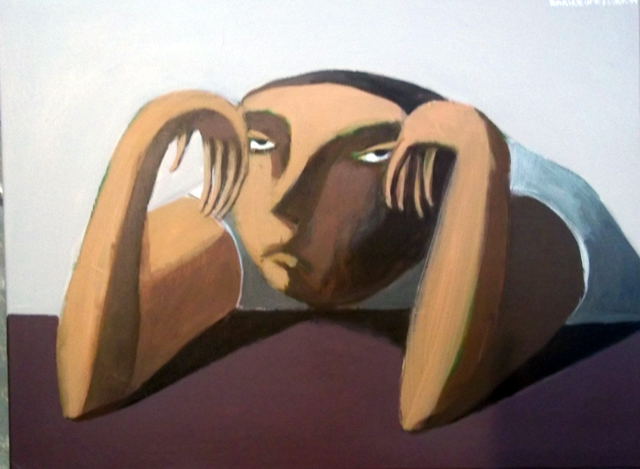

At Wadi Finan Art Gallery, Kurkdjian’s distinctive style is on display, with intimate, probing works of acrylic and mixed media on canvas baring all the facades and barriers that individuals hide behind.

“To this day, I don’t ask people what they think of my work. I don’t care what others think as long as I’m satisfied with my art,” said the artist, who has majored at university in business and psychology.

Although her exaggerated style may at times be unflinchingly candid, Kurkdjian’s art maintains a playfulness that attracts and intrigues viewers.

“I don’t like straight-up tragedy; it drives people away. I don’t want to depress people. Having a whimsical element adds to the contrast and draws people into contemplating the artwork,” she said.

“There is a seductive element in contrast.”

In a painting of a man carrying a child on his shoulders in what appears to be a carefree moment, the predominant colour is a cold, distant blue, suggesting that the intimacy could be superficial.

Depictions of women dominate Kurkdjian’s art.

In one portrait, a woman’s unsmiling face is trapped in braids of her red hair, symbolising a cage.

Another portrait shows a woman with her face almost entirely wrapped in white cloth — a kind of shroud.

“Her mouth is blocked, so she can’t say anything. Only her nose is not covered to fulfil the basic need to breathe. That’s how I see it,” Kurkdjian said, adding that she does not like to enforce a certain interpretation of her work.

“Others might see this as something completely different — a bride preparing for her wedding day maybe.”

The Lebanese artist is fascinated by the symbolism that can be associated with women’s hair.

“Hair is very symbolic. It is associated with femininity. If a woman cuts her hair very short, some view that as a way to revolt against men and patriarchy,” she said.

In one painting, a hand grasps a woman’s hair, as she stares resignedly into nothingness. With her hair being forced into a strict style, the woman is being symbolically controlled.

Another piece shows the back of a woman’s head, with her long hair tied into a severe bun instead of being left to flow freely, perhaps in a reflection of the restrictions confining her into a rigid role.

“I think of myself as a feminist. Women are oppressed everywhere, not just in Arab countries. But women’s victimisers are also victims of society,” the artist said.

“The relationships among women are also distorted,” she added, noting that they revel in each other’s misfortunes instead of offering support.

Kurkdjian also employs nudity in her paintings, seeing it as a reflection of people’s most intimate, unguarded moments.

“When people are naked, they shed all the masks that they hide behind. They are only naked when they are alone,” she said, dismissing claims that showing nudity in art makes it immoral.

“To me, superficial or imitative art is what truly is immoral.”

The exhibition continues through March 19.