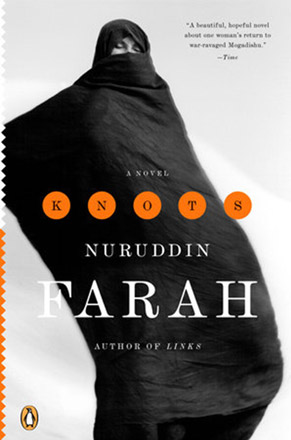

Knots

Nuruddin Farah

New York: Riverhead Books (Penguin), 2007

Pp. 418

Besides telling an exciting, often suspenseful story, “Knots” is a psychological study in novelistic form of human motivation, hope, needs, fears and the function of memory. It’s not that nothing happens in the outside world. On the contrary. It is set in Mogadishu, “a city rampant with the ghosts of its innocent dead”, in the later stages of the civil war. (p. 109)

Though pitched battles have given way to money-grabbing skirmishes, violence looms all around and sometimes bursts out. But most of the narrative — and what makes it engaging and thought-provoking — is author Nuruddin Farah’s descriptions of what goes on in the head of the protagonist, Cambara.

There is a cast of interesting characters, but the unflinching focus, the plot’s catalyst and the magnet for all the others is Cambara, a woman whose childhood was in Mogadishu, but whose family moved to Canada to escape the war. Now she is back, intent on putting an abusive marriage behind her and mourning the death of her ten-year-old son. She doesn’t confide these personal motives to everyone, but justifies her return by saying she wants to recover her family’s property which has been taken over by a warlord. She also wants to stage a play she has written. In short, she wants to reinvent herself. Luckily she can draw on the support of a friend of a friend, Kiin, who is part of the local Women’s Network organising against gun violence, for peace and aiding those in need.

Hardly does Cambara encounter a person, enter a new place or undertake to do something without the author conveying her impressions, calculations, expectations, second thoughts, worries and fears. She is that kind of person who thinks a lot about what she does but in the given situation her introspection is magnified by the events of her recent past and her challenging present. Most of all, she wants to make a difference by drawing people into her circle of positive dynamics, by caring for them if they need it, by opening new horizons before them. “Cambara is famously admired or feared for confronting problems head-on and immediately. Nor does she have difficulty admitting her failings… She is in her element only after she has sorted out a knotty situation…” (p. 94)

Fiercely independent, she likes to be in control, but sometimes a memory is triggered, and she sinks into the angers, humiliation and sorrow of the past. “On the outside, she appears to know what she is doing; not so inside. She is terribly worried that she may not pull it off… But the actor in her takes absolute command of the situation”. (p. 139)

One reads along, ensnared by Farah’s impeccable prose, wondering if Cambara’s good intentions will bear fruit in the extremely adverse conditions surrounding her; meanwhile, one gains valuable insights into human behaviour and Somali society in particular.

Farah is Somali but now lives in South Africa. His writing style is remarkable: He manages to be both elegant and earthy, and uses startling and highly original imagery. The whole book is written in the present tense, and the long descriptions of Cambara’s inner world are often interrupted by abrupt change or action, giving a sense of immediacy. Farah deliberately steers his story to show the vast human and material damage wrought on the individual and the country by years of war, but the thrust of the novel is not just exposing Somalia as a failed state, as one often reads in the media, but pointing to pockets of light that hint at the potential for healing.

It is not by chance that Farah chose a woman to be the protagonist. The whole slant of the story is pro-woman. Though there are a few positive male characters, “reconstructed men” as Cambara calls them, war and all its negative consequences are usually linked to male behaviour, while women’s productive and nurturing role is emphasised. Cambara’s story shows alternatives to oppressive thinking and practices, especially women’s subordination. While some characters exhibit all the symptoms of the country’s collapse into violence and lawlessness, others reject the clannishness and disregard for human rights that have kept the conflict going. The story shows the failure of violence and the value of empathy and collective work.