You are here

‘I’ll flap my wings… until the very end’

By Ica Wahbeh - Apr 02,2023 - Last updated at Apr 04,2023

- Song of a Migrant Bird

- Janset Berkok Shami

- Published by Amazon

- July 24, 2022

- Pp. 442 (14 pages of photographs)

From the very first line of this memoir in which the author asks the eternal philosophical questions “what is life”, “what is your aim in life”, the reader is hooked. But unlike in a whodunit, you do not have to read the entire book to find Berkok Shami’s answer to the latter. It comes immediately: “Hoping for immortality”.

This book, like the “two novels, six short story collections and a book about her friendship with the artist Princess Fahrelnissa, her mentor” by the same writer, is sure to help her reach immortality, in the process making the reader privy to a rich life and sharp, inquisitive mind that could be the envy of many, tens of years younger than her.

Born in Istanbul in 1927, she started writing Song of a Migrant Bird at 86 and completed it when she was 90. At 96, talking to her, one cannot but be in awe. Ramrod straight and quite sprightly for a nonagenarian, lucid, with a subtle sense of humour and full of accounts from her long and rich life, Berkok Shami is a well of stories that are still waiting to be told, and tell she might, despite protestations to the contrary.

“I may have writer’s block,” she said, not fully convinced or convincing. It would be a pity to keep those thoughts bubbling to come to the surface down, for, hers is a prodigious memory and a life worth knowing.

In flowing language that keeps the reader riveted, Berkok Shami introduces to the reader her Circassian ancestors, strong, mostly educated, affluent, influential figures in the Ottoman Empire. The paternal grandfather, hard working, ambitious and smart, would become an army officer sent to the Caucasus front during World War I. But he would also write, “seven books on military subjects”, and the history of the Caucasus, and that may have had an influence on his granddaughter.

The maternal grandmother, “of the Ubykh branch of Circassians” died when Berkok Shami’s mother was less than 40 days old. Raised by a kind stepmother who, together with the entire household, would not let her know she was not her mother, she only found out the truth in the “early married years”, and then, because of a photo in an old album.

Like in Byzantine court intrigue, the writer describes the squabbling of her maternal grandfather’s wives, the colourful lives of close and distant relatives and the education of their different offspring, which all reads like a captivating thriller. But she also talks about her childhood and that of her two brothers, raised by a strong, competent mother and a career officer who would be mostly away or absorbed in his book writing.

Born “in the safety of the Turkish Republic” on April 7, 2027, she has little recollection of her very early childhood in the Sisli district of Istanbul, but vivid memories of her life later, which makes for enthralling reading. One could see the Bosporus yalis, the quarters in Istanbul, Ankara and everywhere else life would take her, smell the jasmine she would choose for the hide and seek game, get an inkling of a relatively privileged life, but also of those days when there were still slave girls and harem oud players, society was stratified and “distinction between classes lingered” even after Ataturk had declared that “citizens of the new republic were stripped of ‘class and privileges’”.

Reminiscences about childhood and school days are interspersed with philosophical musings and questions; the language flows easily, filled with descriptions, humorous observations, sounds, smells and colours that bring places, people and moods to life.

An astute judge of character, the author’s describes friends and acquaintances in detail, pointing out qualities and flaws. Her family — strong mother, withdrawn father, two brothers — is portrayed with care and great complexity.

The main narrative is interspersed with poems and small fictitious stories that, like Scheherazade’s, transport the reader in another world and keep him glued to the pages. One, thus, finds out about summer holidays spent swimming, about Berkok Shami’s school performance and about the trip to Syria and Lebanon where she would meet her future husband. But also about some historical events and societal developments she witnessed in the course of her life, and they were many.

Teeming with characters, descriptions and astute observations about the people she would meet, the book springs a surprise or two (actually quite many) on the reader, to whom individuals who counted one way or another to the writer are introduced. And then, bringing the past to life, she talks about Jordan that she came to know in 1951, when her Circassian husband Khalid brought her to live in Irbid and where she would spend most of her adult life and raise her two children.

“She gives an intimate account of adapting to a new culture, and also shows how modernisation and the recurring regional turbulence of the 20th century impacted people’s daily lives,” says the back cover of the book.

The birth of her two children (a boy and a girl), building the first house (in Marka), basking in “my first publishing success”, in London, “with Cornhill, the quarterly magazine published by John Murray”, “sending my voice to the BBC station’s listeners”, and the marionette making and shows that made the writer and her children “professionals” with their own show on Jordan TV give more detailed insight into the mesmerising life of this ingenious, constantly-on-the-move woman.

Holidays with her now successful adult children, constant questioning of choices made, much introspection abound.

Through it all, the strongest message makes itself heard. Instilled by her mother, it enjoins: “Failure? It is impossible!”

Proof, in Berkok Shami’s case is this book, which can be purchased through Amazon.

Related Articles

Fahrelnissa and I: A MemoirJanset Berkok ShamiIstanbul: Cinius Publishing House, 2016Pp.

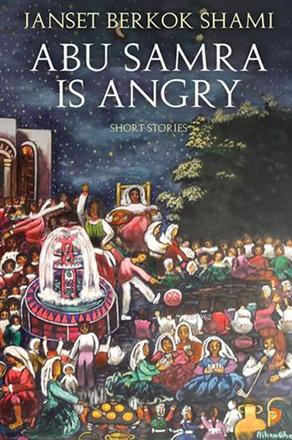

Abu Samra Is Angry: Short StoriesJanset Berkok ShamiIstanbul: Cinius Yayinlari, 2018Pp.