You are here

The light of other people

By Sally Bland - Nov 15,2020 - Last updated at Nov 15,2020

Swing Time

Zadie Smith

UK: Penguin/Random House, 2017

Pp. 453

Despite covering a lot of ground geographically and thematically, British author Zadie Smith’s “Swing Time” is from start to finish the story of a deep, but contentious friendship between two brown-skinned girls growing up in 1980s-90s London. They meet at age seven, when their mothers enrol them in dancing school. As hinted by the book title — the name of a 1936 film starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, both are obsessed with music and dance. It is the driving force in their friendship and in the novel, but their talents are not equal; nor are their backgrounds, despite living in adjoining, dilapidated housing estates. Throughout the novel, the question is posed as to who will survive, much less succeed, in the perilous world of alienation, state neglect, poor schools, drugs, violence and abandonment.

Tracey, the more outgoing of the two, is a natural show-woman; encouraged by her mother, she trains incessantly to make dancing her career. The second girl may be a more talented singer and her appreciation of music is broader, but her inclinations are not developed as she follows her friend’s lead and later the lead of others. It is she that narrates the novel, but the reader never knows her name. Paradoxically, her anonymity generates an intimacy that makes the reader identify more closely with her. But it also signifies a truth that she herself only realises much later: “I had always tried to attach myself to the light of other people... I had never had any light of my own. I experienced myself as a kind of shadow.” (p. 4)

Yet, as narrator, she has a strong, independent voice dissecting childhood experiences and relations with her parents frankly and vividly. She is a perceptive observer of the racial, class and gender factors at play in human behaviour, and thus best qualified to tell the story that the author wants to tell. She and Tracey share these factors, but with important differences. Both are mixed race: Tracey’s father is originally Jamaican, a petty criminal who is mainly absent, while her mother is white and has little education. In the narrator’s family, the situation is reversed: Her father is white and easy-going, a family man who is content with his job in the postal service, while her mother is Jamaican-born and highly ambitious for herself, her daughter, the black community in the UK, and black people generally. A non-stop reader, she puts herself through school and obtains a university degree in sociology and politics, engages in community organising, and after years of standing up for the underdog, is elected to parliament. To the narrator, however, she is an unsatisfactory parent unwilling to indulge her daughter’s taste in music, stylish clothing, and regular meals. Yet, in her own way, via watching old-fashioned musicals, the narrator discovers some truth in her mother’s feminist and black-history orientation, discovering talented black women who were seldom cast as more than servants.

The narrator is jealous when Tracey goes to stage-school, heading straight for performance, but her own enrolment in a comprehensive school paves her way to a university education with a degree in media. This lands her a job as personal assistant to international superstar Aimee, a dynamic but self-centred woman who demands total loyalty from her staff. Entering the world of the super-rich for the first time, the narrator’s life becomes one of incessant travel, facilitating Aimee’s performances. Soon she is as much at home in New York as in London. When Aimee, who thinks one can change the world with sheer will power and sufficient funds, decides to open a girl’s school in The Gambia, the narrator travels there repeatedly, and questions of poverty and equality, posed in the narrator’s life in Britain, take on global dimensions. Many misconceptions about development aid are exposed, and a number of racial myths explode as the narrator is not considered black by Africans, but lumped together with the rest of Aimee’s staff as “the Americans”, though only one of them was born in the US. On the other hand, the narrator finds the unexpected in the midst of poverty: Watching how people respond to a traditional dance, she thinks: “here is the joy I’ve been looking for all my life”. (p. 165)

Living in the shadow of three strong women, the narrator chronicles her attempts to carve out her own space amidst the issues of loyalty and betrayal posed by each of these relationships; she has to make hard choices.

“Swing Time” is a dazzling, post-colonial novel, highlighting the changes experienced by successive generations of immigrants and the persistent gap between the ex-colonial powers and former colonies. Spanning three decades, it also traces how media has changed personal relationships, from the television and videos watched by the two little girls to the fax, e-mail, digital, cell phones and the internet. Most of all, it chronicles the importance of music in creating happiness.

Smith’s writing is superb throughout. Every scene is vividly painted with details that are never superfluous but add layer-upon-layer to one’s understanding of the characters, their situations and the power relations among them. There are few polemics but rather a steadily-building, underground current bearing witness to just how absurd racism is, in addition to being cruel and unjust. “Swing Time” is available at Readers Bookshop.

Related Articles

The Valley of AmazementAmy TanNew York: HarperCollins, 2013Pp.

Dance Dance DanceHaruki MurakamiTranslated from the Japanese by Alfred BirnbaumLondon: Vintage, 2003, 393 pp This is Murakami’s sixth n

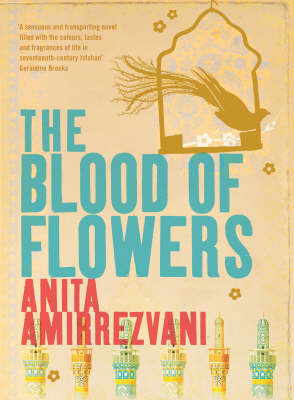

The Blood of FlowersAnita AmirrezvaniLondon: Headline Publishing Group, 2008Pp.