You are here

‘If Shamil were here today…’

By Sally Bland - Mar 11,2018 - Last updated at Mar 11,2018

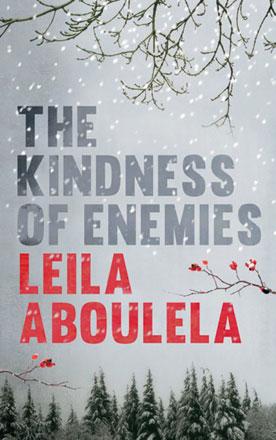

The Kindness of Enemies

Leila Aboulela

New York: Grove Press, 2017

Pp. 338

Like in her previous novels, the role of faith is the overarching theme in Sudanese writer Leila Aboulela’s newest book, “The Kindness of Enemies”, but she also explores hybrid identities, divided loyalties and difficult choices — between resistance and adaptation, between war and peace.

These themes gain nuance and depth by being pursued in widely divergent settings. There is much excitement and suspense, as dramatic events unfold from Scotland in 2010, to the Caucasus, Georgia and Russia in the mid-19th century, with a brief but crucial interlude in Sudan.

The real focus, however, is the characters’ inner lives — emotional and spiritual — which Aboulela describes subtly yet poignantly.

The link between the modern plot and the historical one is Natasha Wilson, born Natasha Hussein to a Russian mother and a Sudanese father, who narrates the now-time chapters. Leaving her Muslim, Sudanese background behind after her parents divorced, she is now a university professor who seems to have adapted to life in Scotland. But small, random things elicit memories of a former life, a different life she might have led. “I was usually restrained, keeping back the shards and useless memories. I had worked too hard to fit in… Many Muslims in Britain wished that no one knew they were Muslim.” (p. 6)

Arriving in London in 1990, just as Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, she changes her surname. But despite her outward success, one feels she is lonely and missing something. Perhaps that explains her choice of research topic: Imam Shamil, a Sufi who led the struggle, or jihad, against Russian domination in the Caucasus from 1830 to 1859.

Natasha’s narrative highlights the psychological state of siege experienced by Muslims in the West due to the post-9/11 “war on terror”, while the historical chapters vividly depict the harsh Russian military siege to which the people of the Caucasus mountains were subjected for decades, until Shamil surrendered.

Both narratives pose the question of whether jihad means war or an internal struggle, and the comparison explains why, in Natasha’s words, “the founders of Political Islam… never took Shamil as a role model.” (p. 227) Yet, as she discovers, Shamil holds attraction for some young Muslims in Britain.

One of her students tells her: “If Shamil were here today, he wouldn’t have sat back and let Muslim countries be invaded. He wouldn’t have given up on Palestine and he wouldn’t have accepted the two-faced wimps we have as leaders.” (p. 10)

Aboulela’s aim seems to be more than eliciting sympathy for Muslims under siege; she interrogates the choices they make. In her telling, Shamil stands out as an intelligent, charismatic hero, a compassionate man of principle who believes that his struggle will succeed if God wills it so. Thus, when faced with defeat — his followers starving, their homes and hideouts destroyed and his commanders defecting — he can no longer ignore the judgement of his Sufi mentor who views jihad as the non-violent struggle with one’s self.

Gradually, Shamil becomes more than a research topic for Natasha. Speaking as a historian, she says, “We, staunchly secular and sure of ourselves, plunged into politics and economics, ideology and warfare, power and pressures, then hit against the faith of the characters we were studying.” (p. 227)

Other characters face life-changing circumstances and choices, and Natasha is not the only one to choose adaptation. Shamil’s oldest son, Jamaleldin, is kidnapped by the Russians, made the tsar’s godchild and trained as a Russian military officer.

By the time Shamil is able to capture a hostage important enough to exchange for his son, Jamaleldin has forgotten his native language, no longer practices his religion, and dearly loves the music, dancing, culture and advancement of Russian city life.

Though he wants to see his family, he returns to the spartan life in the Caucasus only out of a sense of duty, and in hopes of convincing his father of the advantages of suing for peace. Yet, it seems tantamount to betrayal.

The hostage for whom Jamaleldin is exchanged is Princess Anna, whose native Georgia charted a different course than the Circassians, Chechens and Dagestanis. By ceding Georgia to Russia, they attained peace and prosperity.

Yet, Anna is so impressed by Shamil that she begins to ponder what Georgia lost in the process. Jamaleldin and Anna both experience “the kindness of enemies”, as does Shamil after his surrender, but Aboulela makes it clear that it is conditioned on abandoning resistance, but not necessarily one’s integrity or beliefs.

Aboulela tells a fascinating story with political, psychological and spiritual implications. From the first page, she plunges the reader into unexpected situations with no background descriptions, which heightens the impact of the plot. Memories and dreams alternate with hard reality.

Her prose is lyrical and evocative but never flowery, and she deftly switches style from chapter to chapter in step with changes in the setting and turn of events. This is both an enlightening historical novel and a bold intervention in the very current debate on the interplay between politics and religion.

Related Articles

Don’t Panic, I’m IslamicEdited by Lynn GaspardLondon: Saqi Books, 2017Pp.

Istanbul: Journal of Caucasian Studies (JOCAS), September 2015-March 2017The Journal of Caucasian Studies (JOCAS) is a peer-reviewed, bi-ann